Following routine preventive maintenance procedures can save in the long run and keep your engine in top shape, avoiding the necessity of a premature overhaul or other costly maintenance procedure.

Following routine preventive maintenance procedures can save in the long run and keep your engine in top shape, avoiding the necessity of a premature overhaul or other costly maintenance procedure.Preventive maintenance can be expensive, but neglect is even more costly. Systematic PM saves you money in the long run by reducing the chances of equipment failure on the road and reducing time lost to repairs. It also helps reduce the severity of failures if they do occur. Some industry estimates say preventive maintenance can cut breakdown costs in half, and a properly maintained engine will last much longer and also use less fuel.

Nearly all owner-operators change their oil often or use oil analysis to determine precisely when to change if at more distant intervals. Also important is using quality oil and filters, as well as timely coolant servicing (including system flushing), because these practices will help make an engine last longer. Using synthetic transmission and axle lubes and changing at required intervals also will help the life of those components.

Don’t neglect other less-familiar practices. Adjusting the overheads after break-in and then at the required infrequent intervals saves fuel, reduces oil sooting and wear, and is likely to prolong the life of both valves and injectors. Replacing injectors before combustion gets too dirty also will prolong life. Using quality fuel filters will, in turn, prolong injector life. Various long-life antifreeze options, such as extended life coolants and coolant filters that add supplemental coolant additives on a controlled basis, should be considered even though the initial cost may be higher.

A simple maintenance plan that doesn’t require technical skill and special equipment will include tires, engine oil, wipers, lights, filters, coolant and belts/hoses. A more technical PM will include brakes, drive axles, wheel seals, transmission, batteries, exhaust, driveline, suspension, steering, clutch and engine.

AN OUNCE OF PREVENTION

Become familiar with every inch of your truck and know which components can fail and under what circumstances. You don’t have to be a mechanic, but you should be familiar with a truck’s mechanical operation and how systems interact. Manufacturers offer schooling, normally available for free or at nominal cost, and they typically recommend a standard PM schedule for every model. The Technology & Maintenance Council of the American Trucking Associations also provides PM guidelines for tractors and trailers. Follow these schedules diligently, and you’ll head off a lot of trouble.

Daily pre-trip inspections, required by the U.S. Department of Transportation, can help identify problems before they become emergency situations. A leaking differential should be repaired before the lubricant loss causes component failure. Early warning signs found by engine or driveline component oil analysis can alert you to serious problems before costly troubles occur. If you have a truck with more than 300,000 miles, consider running a dynamometer test once a year.

Always look for common problems such as seal leaks, loose bolts, chafed wires and hoses, improper adjustments and worn, broken or missing parts. If you cannot recognize these problems, have a qualified technician inspect your rig every six months. An alternative is having lubrication service done at a dealer or truck stop where experienced technicians will look for problems as they work.

The same can be said for maintaining a trailer. For a dry van, check the suspension during pre- and post-trip inspections, perform a pre-load adjustment and annual inspection on the bearings, check the brake lines regularly, and check tire inflation and wear regularly. Also replace the work scuff liner to protect the trailer walls, check the roof during pre- and post-trip inspections for holes and leaks, inspect the threshold plate often, and inspect the floor to spot weak spots or small holes.

POTENTIAL FOR LOSS

Suppose your truck’s engine blows while you’re under a load. Your carrier likely will have to dispatch another driver to deliver the load. Meanwhile, you’ll have to pay for the tow and find a replacement engine. If you lose a week’s worth of work at, say, $1.10 per mile, you’ve also lost $2,750 in revenue. The lack of attention to your engine could end up costing more than $20,000:

Rebuilt engine: $18,000

Road service: $650

Lost revenue (current load): $1,100

Lost revenue (future loads): $2,750

Total loss: $22,500

BEGIN AT THE DEALER

The best time to start a regular PM program is when you’re buying your truck. If the dealer doesn’t volunteer detailed information on maintenance, ask for it. A good dealer is happy to give advice about oil changes, lube and filter replacement, and other maintenance. Take advantage of your leverage before you buy to get all the information you can. Manufacturers’ websites often offer detailed information.

Separate warranties often are written on the engine, transmission and other components because they are supplied by different entities. Find out the duration of the warranties and what it will take to maintain their validity. You might want to consider extended warranties, where available.

Choose a dealer carefully. Make sure its service department has the technicians and equipment to handle major repairs and that they have a helpful attitude. Talk to the parts and service managers, and form a relationship. From there, take the same relationship-building approach to local tire and engine shops, an alignment shop and an air-conditioning shop. Dealing with pros who specialize in one maintenance item is key to holding costs down in the long term. Take time to let the service manager or even the owner of the shop know your goals and plans. Ask their advice about maintenance scheduling.

Do things like occasionally taking pizza to the mechanics, which can go a long way toward building a relationship with the people who are working on your truck. Also compliment the work once in a while instead of complaining that everything is too expensive. Another great way to build relationships is through referrals. If you’re happy with a shop’s work, spread the word to other operators.

KEEP GOOD RECORDS

Only with complete and accurate records can you track the work done on your truck and prove that required work has been done. Committing every shop visit to paper and creating a calendar of scheduled visits will pay off. You also should keep a schedule of future work to be done. This schedule will help you avoid overlooking something vital.

Make copies of the blank maintenance service report in this chapter and use it to keep a record of every dollar you spend on your truck. Keep receipts on repairs. Keep old parts in case of a warranty dispute. When you use the truck service report, note all warrantable purchases and repairs, and include a record of your out-of-pocket expenses, such as cab fares, meals and motel stays related to time lost due to repairs. Otherwise, you won’t be able to file warranty claims properly, and your profits will suffer.

Good maintenance records can help you determine average miles per gallon, expenses on a per-mile basis and other key benchmarks helpful in cutting costs. They also can help you spec your next truck.

TIME TO TRADE

Maintenance costs typically rise in the third and fourth ownership years. Fifth-year costs often drop because the truck needs certain work in its fourth year that isn’t required the next. However, the cumulative cost of maintenance – your average cost per year since you took ownership – and your cost per mile still increase each year.

No matter how rigorous your PM efforts, your rig eventually will wear out. The time will come when you’ll spend more on maintenance than you would for a new truck. How will you know when that time comes? Your maintenance records will tell you.

Create a maintenance budget, and track your maintenance expenses. When they rise to a point that seems excessive, check with your business services provider, who can help you determine how much your fuel, oil and maintenance costs have increased due to the age of the truck. Your insurance agent can help determine how an equipment upgrade will affect your premiums. Your financing source can discuss various options for the purchase of a new truck, and your accountant can explain potential depreciation benefits that would accompany a new purchase.

No magic formula tells you for certain when to upgrade. Industry experts say you should consider replacement when your fuel mileage drops 2 mpg or more in spite of conservation efforts, or if truck technology develops to the point that a new truck would get an additional 2 mpg. Another indication to trade is when your total maintenance costs reach 15 percent of your gross revenue.

As a rule of thumb, consider a new purchase when the principal, interest, maintenance and operating costs of an old vehicle are higher than the comparable costs attached to a new vehicle. The estimated resale value of the old vehicle, coupled with any manufacturer’s incentive on a new vehicle, may offset the higher cost of a new vehicle’s principal and interest. At this point, a trade makes sense.

SAVING FOR MAINTENANCE

Every good PM schedule begins with establishing a maintenance escrow savings account. An industry standard for maintenance escrow savings is based on a time-proven formula:

OVERHAUL OR REPLACE?

When warning signs that a major component, an engine or your entire truck needs serious attention, it often raises a tough question: Should you rebuild, repair or replace it? You don’t have to settle for an educated guess or a knee-jerk reaction to initial cost. By assessing the truck’s value, examining costs associated with various decisions and considering other factors, you can arrive at a well-informed choice methodically.

Costs such as $18,000 to $20,000 for an engine overhaul, $5,000 for overhauling the transmission and $3,000 to $4,000 to overhaul the rear end might push you toward purchasing a newer truck. That could be the best decision, but the size of such numbers alone isn’t enough to make that call.

Cost per mile is one of the best ways to compare the merits of repairing, rebuilding or replacing a component or the entire truck. In this example, a new alternator would last 150,000 miles, while the rebuilt part would last 100,000 miles. The cost per mile for covering the truck’s remaining longevity of 300,000 miles is slightly less when using the rebuilt components.

WAYS TO SAVE MONEY ON MAINTENANCE

When asked why they’ve done a poor job of preventive maintenance, too many owner-operators say they were trying to save money. But there are many ways to save money on maintenance without skimping and courting disaster.

STAY ON SCHEDULE. Plan your maintenance schedule as thoroughly as you plan this week’s haul, and stick to it.

SHOP AROUND. Few owner-operators cite price as their primary factor in deciding where to buy their oil. They give more weight to convenience, but sometimes the cost of convenience can be high. Do price comparisons online or over the phone – especially if you haven’t done so in years. Also look into the benefits of buying as part of a group or via a fleet, a membership organization or a truck stop or warehouse chain.

PLAN FOR EMERGENCIES. A front tire with a nail in it, multiple lights out because of a short circuit, or a suddenly failed brake lining might put even the most maintenance-savvy owner-operator out of commission – or out of service, if a DOT inspector finds the problem first. Many of the industry’s top truck, engine and other equipment manufacturers have created 24/7 help centers accessible via a toll-free number or proprietary smartphone application. These centers quickly can put you in touch with the nearest service outlet for emergency assistance.

Independent breakdown services offer similar assistance, two well-respected services being FleetNet America and National Truck Protection service networks. The National Truck & Trailer Services Breakdown Directory is available to search for services in particular areas.

CATCH OVERLOOKED ITEMS EARLY. Timely fixes to these problems can reduce thousands of dollars a year in operational costs by helping avoid breakdowns and providing better service to your customers.

•Charge air cooler. The CAC sits in front of the radiator and looks like a radiator. It is designed to cool superheated air from the turbo before it gets into the intake manifold for more efficient combustion. Seeing a water leak from a radiator is easy, but your CAC needs to be pressure-tested to find leaks. You can make or purchase a test kit, or have it done at any engine shop. Each engine manufacturer sets a limit on how much CAC pressure loss is acceptable, usually 5 to 7 pounds in 15 seconds. But given the immediate drop in fuel mileage a leaky CAC causes, it makes sense to replace a unit that leaks just 2 pounds in 15 seconds. At that level, at 2,500 weekly miles at 6 mpg and $3.50 per gallon for diesel, you’d be losing $112 a week.

•Crankshaft damper. Most engine shops will tell you this doesn’t need to be replaced. They don’t even replace it on an in-frame. This is a mistake. The crankshaft damper, designed to reduce torsional twisting from the force of the connecting rods being driven down by combustion, wears out. Consequently, engine force and vibration are not transmitted throughout the entire frame and driveline. This leads to many problems, not the least of which is driver fatigue. Maintenance problems run the range of broken alternator brackets, broken air-conditioning brackets, clutch and driveline problems and even loose or faulty electrical connections. There is no way to inspect a crankshaft damper: Replacing it at 500,000 miles is recommended to avoid problems. It will cost $700 to $1,000, more in some engines.

•Flexible rubber fuel lines. These can deteriorate internally with no visible wear or damage. Internal deterioration can cause lines to swell and restrict fuel flow, triggering fuel-mileage declines and power loss. Trucks with fuel mileage issues can benefit from line replacement ($300 to $400) to the tune of 0.3 to 0.4 mpg. If your truck has more than 700,000 miles and an unexplained loss in mpg, it would be recommended.

•Factory mufflers. These can cause exhaust restrictions from day one. The longer they’re used, the more soot buildup you see in the muffler itself, and the more exhaust restriction is created. Restriction robs your engine of performance, power and mpg. You can install a high-performance flow-through muffler on most trucks for less than $200, and your return on investment is nearly immediate. You’ll also notice much better throttle response.

•Shock absorbers. When shocks are worn, it can lead to excessive vibration, irregular tire wear and driver fatigue. Many experts recommend replacing shocks every time you replace tires.

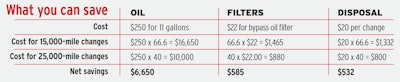

BUY OIL IN BULK. The do-it-yourself oil change is a standard for many owner-operators, especially those with their own authority. A one-truck operator can save almost $200 a year by moving from gallon jugs to 55-gallon drums for oil purchases, assuming 125,000 miles per year with an oil change every 25,000 miles. A 10-truck fleet can save about $2,700 a year by changing from gallon jugs to bulk delivery in a tank.

Disposal is normally an associated cost, but if you live near an oil-recycling refinery, you might be able to sell your waste oil. As fleet size approaches 10 vehicles, it can pay for you to burn your own oil to heat your maintenance shop. Major refiners often don’t handle distribution of bulk oil to the individual customer. A first step in determining whether buying bulk oil makes sense for you is to contact a local distributor and explore pricing.

Extending oil life

Oil might cost more than you realize, especially if you’re not getting maximum use of it. Do a typical change yourself, and it still costs about $250 or more for the oil alone. But assume you extend your change interval from 15,000 miles to, say, 25,000 miles. That extension over the million miles of an engine’s expected lifetime would save a lot. Allowing a modest amount for disposal costs and nothing for downtime or labor, the total savings from adding 10,000 miles to change intervals over 1 million miles would amount to about $7,787.

Oil life is quite flexible. A competent operator can extend that life significantly by paying attention to maintenance and altering his operational behavior. Minimizing idling time alone will extend the life of oil significantly because idling puts more undesirable stuff in the oil than even hard driving. Responsible refiners are willing to stand behind their products even when extending changes. Operating and maintaining your vehicle or vehicles according to the experts could allow you to extend changes without fear of problems. It could also reduce costs and give you more downtime.

THREE KEYS TO EXTENDED DRAINS

•Use good filtration practices. Proper filtration extends the life of oil. Use a filter that will meet all the engine manufacturer’s specifications, and always change it at the recommended interval. Involve the filter supplier in considerations of extended drains. You might need better capacity for dirt or better internal construction. You may need a synthetic filter media.

•Choose the right oil grade. All premium oil refiners offer diesel oils that are extended drain-capable. Lubes with a lower initial viscosity grade number are better for cold starting under harsh conditions. This allows many operators to curtail idling, which helps extend change intervals.

•Get routine oil analysis by a qualified laboratory. At any point of potential oil change, the oil is either clean enough to keep using it or dirty, already causing damage, so you better get it out. Oil analysis allows you to not change the oil until it really needs it. It’s a critical requirement to supplement proper maintenance. New engines exhibit levels of contaminants that remain from initial construction of the radiator, oil cooler and exhaust gas recirculation cooler. Knowing not only the miles on the oil, but the total hours the engine has run, is critical to knowing whether a contaminant is coming in from outside and likely to cause damage. If you buy oil from an oil supplier and consistently use the same brand, it’s possible the oil refiner will offer free oil analysis. If not, ask your supplier or engine dealer for information on a reputable lab. A good analysis report will cost $30 to $50. Analysis should be performed at every drain if using extended intervals.

The lab will test for wear metals, including iron, copper, lead, aluminum, chromium, etc. This tells if components are wearing out and which component it might be. Lead and copper together indicate bearing wear, while iron and chromium together could mean cylinder and ring wear. The test will show if the necessary additives are present in the correct quantities and if contaminants – such as fuel dilution, soot, water or coolant – are present in dangerous quantities. Finally, the test will show the oil’s physical properties, such as viscosity, total base number (TBN), oxidation and nitration.

That information also allows you to correct budding problems before they cause damage. An oil analysis report indicating fuel dilution can be a sign of a failing injector; if that goes unrepaired, it will cause excessive wear metals and bearing failure.

Coolant intrusion is another problem that can go unnoticed but is detected easily with oil analysis. Coolant in the oil will strip out the zinc and cause high wear metals and ultimately premature engine failure. Increasing soot levels are an indication of incomplete fuel combustion, causing higher fuel consumption and loss of performance. When you see high soot levels, check the charge air cooler (CAC) and for exhaust restriction and low operating temperatures.

Considered over the engine’s million-mile lifecycle, you can save nearly $8,000 on oil, filter and disposal costs alone, plus shop costs if you don’t do the changes yourself.

TIPS ON DOING IT YOURSELF

While your free time is valuable, every maintenance job you can do yourself is a job you don’t have to pay someone else to do. Common do-it-yourself jobs include fluid and filter changes, mounting and demounting tires, and routine work on relatively simple components such as wipers, lights, belts and hoses.

The basic rules always apply:

•Get expert advice for any new project, and be sure you aren’t violating warranties.

•If you’re not comfortable doing any job, take it to the shop.

Following find cost breakdowns for some common jobs:

Greasing. Greasing is simple and inexpensive. You can purchase a high-quality lever-action grease gun, grease and wipes for less than $50. Your cost for each job: $10. Shop cost: $45 to $85. Time: 45 min.

Changing Fuel Filters. This doesn’t require many tools, but learning the proper technique is important, so consult your owner’s manual. You’ll need a band clamp of appropriate diameter for fuel filters, a catch pan and a small container of fuel. Your cost: $15 per job. Shop cost: $25 to $30. 30 min.

Cleaning Connections and Cables. Special battery terminal cleaners are inexpensive, and other connections can be cleaned with sandpaper or steel wool. Your cost: $10 per job. Shop cost: $80 to $100. 1 hour.

Inspecting Cooling System. To check your system, buy test strips and measure antifreeze concentration and the level of anticorrosion additives. Your cost: $2.50. Shop cost: $20. 15 min.

DIY MAINTENANCE RESOURCES AT OVERDRIVEONLINE.COM

Draw on the wealth of maintenance coverage featured in Overdrive via the magazine’s website. A list of how-to articles as well as other stories, with links to the archived stories, is available via overdriveonline.com, search “Staying ahead of the inspectors.” Areas covered include tires and brakes, lights and electrical systems, engine and drivetrain, trailers and others.

23 TOOLS TO TAKE ON THE ROAD

•A set of eight hand wrenches and sockets.

•Two standard adjustable crescent wrenches, one 6 inches and one 10 or 12

•A fuel-filter wrench.

•Two vise grips, one 6 inches and one 8 inches.

•A hacksaw with spare blades.

•A carpenter’s hammer.

•A machinist’s or ball-peen hammer.

•A 30-inch crowbar or pry bar.

•A set of flathead, Phillips and star-tip screwdrivers in various sizes.

•Rolls of duct tape and electrical tape.

•A can of WD-40 or some other spray lubricant. Don’t lose the straw.

•A knife.

•Wire and metal snips.

•An electrical current tester.

•C-clamps.

•An air-pressure gauge.

•An awl.

•Pliers of various sizes.

•Flashlights of various sizes, including one for your pocket, one for flagging help and a large freestanding lamp for night repairs.

•Jumper cables, at least 20 feet long.

•Towing chains, 20 feet of 20,000-pound strength.

•A torque wrench.

•A handheld remote diagnostic unit that communicates with the truck’s onboard computer.

DEALING WITH DEALER SERVICE

Many longtime owner-operators have had at least a minor conflict with a dealer over a repair. Whatever the problem, never underestimate the need for effective communication. As long as you’re talking to someone, a compromise is possible.

BASIC STEPS

- Don’t just show up and demand instant service. You’re hardly the only one with a “hot load.” Making an appointment is ideal.

- Make accessible your complete service and warranty records, and never tell the dealer what to fix. Instead, explain all you know about the problem, and if possible, take a service person on a test run to recreate conditions.

- If diagnosis is a problem, ask dealer personnel to discuss the issue with factory service people. If local techs are too busy, call the factory reps and ask them to assist the dealer or allow you to relay relevant information.

- When a problem is not identified readily, authorize an hour or two of labor for diagnosis. It’s cheaper than experimenting with repairs and more likely to yield results.

- If speaking to a service representative is a dead end, appeal to the service manager, dealer managers and ultimately the owner. Failing that, a factory rep might be able to influence the outcome. Understand that the manufacturer cannot force the dealer – an independent business entity – to do anything.

- Even if all else fails, suing can be expensive and is not likely to succeed unless the dealer clearly is violating the terms of a warranty, disobeying an applicable law or acting in bad faith.

GENERAL TIPS

- Work through the selling dealer, who has a greater motivation than other dealers to do warranty work or go to bat for you with the factory.

- Keep your cool, and demonstrate a positive attitude. No one wants to cooperate when they’re treated rudely.

- Having a good long-term relationship with dealer personnel will help. Your best leverage is the ability to take your steady business elsewhere.

SPEAKING ‘DPF’

You’re chasing sun on 40 out past El Paso, Texas, maybe a little Willie and Waylon on the stereo while you gaze idly at the landscape. You’re wondering how long it will take to reach a peak on the horizon when a little yellow light on the dash winks on, spoiling the serenity: Your diesel particulate filter needs attention. Since the year 2007, heavy-duty diesel engines have had DPFs installed to meet increasingly stringent particulate-matter-emissions regulations from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. In most situations, the warning lights on operators’ dashes don’t mean the truck is in any real trouble. Neither is the engine. That light is just telling you a normal function in the life of a post-2006 diesel engine has to take place. Even better news is that it probably will require very little of you.

Still, as with any truck component, failures can happen. If you understand DPF maintenance cycles, you’ll have a better idea of when you need to get help and when you can get back to watching the scenery.

WHAT A DPF DOES. Any truck manufactured after Jan. 1, 2007, has a DPF. There’s actually a lot of heavier-than-air stuff in diesel smoke. EPA calls it “diesel particulate,” better known as soot. These are ultra-fine particles of elemental carbon with adsorbed compounds such as sulfate, nitrate, metals and organic compounds. A DPF is engineered to trap such particles.

A DPF is not a spin-on type filter like an oil filter or a cartridge-type like a fuel filter. The ceramic filter itself, a little smaller than a loaf of bread, sits in a metal canister that also acts as a collection device for soot.

WHEN TO CLEAN. Much like a clogged catalytic converter on your car, a plugged DPF interferes with efficient exhaust flow. It can lead to compression or combustion problems if left untreated. In most cases, the DPF burns off accumulated soot through either a “passive” or “active” regeneration.

In a passive system, the engine’s computers track certain variables – like emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and temperatures – and heat up the DPF to oxidize (burn off) the soot. In an active regeneration, diesel fuel is injected directly into the exhaust stream, usually right behind the turbocharger. This fuel evaporates and coats the DPF catalyst, causing a chemical reaction to oxidize any remaining soot, leaving a residual amount of ash. Either event is likely the reason that yellow dash light came on. If the DPF warning light is blinking, this is what is happening. If the light comes on and stays on, it’s time to get the DPF cleaned.

While the regeneration process burns off accumulated soot, it does not clean out the actual filter media that trap the particulates. And because the regeneration process will not burn off all the ash, eventually it will collect in the canister and fill it up. This normally happens at about 400,000 miles for heavy-duty engines. But if you have a turbocharger or fuel injector failure, it could lead to the filter media becoming saturated before the mileage interval is met. So the little DPF light might indicate a bigger problem, depending on the mileage since the last cleaning.

It’s not an immediate issue unless you’re at about the 400,000-mile service interval. Usually you’ll know you’re getting close because the regenerations will be getting more frequent. If you notice more and more lights and regenerations well before 400,000 miles, you may have a bad injector or turbo. In any event, if you wait too long, your performance will fall off noticeably as the engine derates due to excessive exhaust backpressure.

Two types of DPF ash cleanings include changing out the DPF – usually because it is chipped, cracked, burned or melted – which takes about 2.5 hours, and a full cleaning, taking around four to five hours. Some manufacturers have quick exchange programs whereby you trade out your dirty DPF for a clean one. Cleaning is not cheap: A DPF cleaning machine costs about $75,000, which helps explain why getting the unit cleaned can run you about $500. If you’re replacing the DPF, you’re probably looking at $1,200.

A 2015 Overdrive survey found that emissions systems have become the No. 1 maintenance issue for 23 percent of buyers of new post-2010 emissions-spec equipment. For buyers of new 2007-’09-spec equipment, that number jumps to 29 percent. It’s even worse in the used market, with almost four in 10 owner-operators reporting emissions problems for 2010 and newer equipment, and three in 10 for 2007-’09 equipment.