Simple failure to pay for a delivered load isn’t the only way that brokers stiff owner-operators.

Simple failure to pay for a delivered load isn’t the only way that brokers stiff owner-operators.Small fleet owner Scott Jordan once had something of a maxim he’d repeat about his business dealings. “In all the years I’ve been in business,” around seven years as an independent, he’d say, “I’ve never been screwed over by the broker or shipper, only the trucker.”

Last year, that changed in a big way on a load that Jordan booked for one of his owner-operators. Working with a sizable broker, he was led to believe the freight was something of a need-it-now item. Complications ensued, appointments for delivery were rescheduled repeatedly, and rate confirmations were updated to reflect the changes. After reaching an agreement to store the load for about a week, it turned into a $3,800 load, well over the initial rate.

Yet the broker attempted to back-charge Jordan’s fleet through his factor for the storage charges, alleging Jordan and his owner-operator threatened to hold the load hostage. Transactions ended. Jordan was out $2,600 in revenue but paid his owner-operator, who had put up with all the rescheduling, the full $3,800.

Now all bets are off when it comes to this broker. “This is like the horror stories that you always hear about. I was one of those guys who said, ‘This is never going to happen to me.’ ”

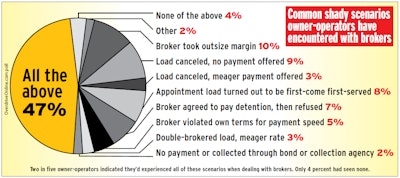

If recent Overdrive polling is any indication, believing it would never happen might have been naive. Almost all respondents say they’ve encountered some fraud or abuse from brokers.

As is common in such disputes, Jordan viewed taking the case to court as too costly. This rationale means a crooked broker often walks away understanding that, at least in the short term, subterfuge of this type is A-OK. Then he reloads to do it again.

The temptation of easy money can lure less-scrupulous individuals into a trap that self-perpetuates through the industry. Say a “dispatcher sees a broker rip him off for $50,000 and walk,” says Ron Reesor, marketing manager for freight-collection agency Baxter Bailey & Associates. “Nobody’s going to prosecute. Dispatcher says, ‘I could do what he did. I could steal a bunch of money.’ If there’s no real penalty for doing something illegal that is extremely profitable,” what’s to stop the crooks?

There are tools and best practices to at least avoid getting in such situations: Practice attentive negotiation with unfamiliar brokers. Cement relationships with those you’ve dealt with previously. Know the tools available to verify creditworthiness, and if all else fails, collect payment via a third party.

Though credit-checking tools continue to proliferate via load boards and other freight utilities commonly employed by owner-operators, they aren’t foolproof. Many haulers continue to get hit with the blunt end of common shady practices, some with new twists on old scripts. From mysteriously canceled loads to getting stiffed on accessorials to the worst – a broker with no intent to pay whatsoever – keep your eyes peeled for red flags, ask plenty of questions, and don’t avoid researching unfamiliar brokers and shippers.

The worst of the worst

The fact that Baxter Bailey exists and is doing a hefty amount of business, with as many as 5,000 clients, is clear testament to the issues that trucking companies face in dealings with crooked brokers. Reesor and his son founded their company after watching their 200-plus truck fleet die. “I attribute it fully to brokers ripping us off,” Reesor says.

The carrier had some direct customers, but it was load board-dependent getting out of the Northeast. One too many unpaid loads sounded the company’s death knell. Reesor went to the Federal Bureau of Investigation about one of his problem cases, a broker based in St. Louis who had operated five companies in succession over two years, running up claims on a series of sureties. He’d probably never paid a carrier, Reesor believes.

Marold Studesville of Transportation Financial Services, whose primary business is in providing those required $75,000 surety instruments for brokers, has seen such happen himself. In 2014, following a run-up in claims on a client’s surety, Studesville realized the broker previously had had three other companies that had closed, and he was running up claims on the fourth.

As a surety processor, he’s required to notify the broker of claims and give the broker 30 days to replenish the minimum $75,000 financial security. But he’s also required to notify the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration of pending cancellation of the $75,000 surety instrument 30 days in advance. That, ultimately, can amount to an extra 60 days during which the crooks are free to “continue booking, dispatching and billing shippers for movements they probably never even contemplated paying the motor carriers” for, Studesville contended in comments on the Federal Register. He says the loophole is exploited routinely by shady brokers.

Studesville says he’s hopeful for federal action on the ability to immediately suspend brokers about to be insolvent. Provisions in MAP-21 provided federal authority for such an immediate suspension of the broker’s authority upon notification of claims on the bond/other surety instrument. But, Studesville contends, regulators haven’t bothered to put that authority into practice.

He says rulemaking is high on FMCSA’s priority list, according to his conversations with representatives there.

In response to Overdrive queries, FMCSA confirmed that it was in early regulatory stages for a rulemaking regarding broker financial security, which would indeed seek industry response on “the immediate suspension of a broker’s authority upon cancellation of the surety bond/trust,” said FMCSA spokesperson Sharon Worthy. The rulemaking will begin with an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking to solicit industry input.

The case of Reesor’s former fleet, however, illustrates what many know about FMCSA and federal law enforcement priorities — financial crimes in freight have taken a backseat to safety matters since the 1990s end of the Interstate Commerce Commission. It’s well-publicized that FMCSA maintains a focus on so-called “chameleon” or “reincarnated” carriers, trucking or bus operations shut down over safety issues that pop up under a different name with a new authority often in an entirely new geographic location. A similar chameleon dynamic among small brokerages is evident in any conversation about financial fraud, but many believe it’s not being addressed.

FMCSA’s Worthy notes that, “while FMCSA does screen applications for operating authority for reincarnation behavior [of brokers], it is infrequent that a broker’s authority is revoked.”

Investigatory reticence extends through to the FBI as well. When Reesor sat down with an agent to look over information he’d collected about the St. Louis-based broker before founding Baxter Bailey, the agent ultimately told him, “ ‘You’re telling me this guy’s a criminal, but it looks to me like he’s just a bad businessman.’ That was it, meeting’s done. If it happened to me, how many others did it happen to?”

The impending rulemaking Worthy references above, she believes, “will assist in identifying brokers with insufficient financial security, and/or conducting fraudulent activity.”

Reesor and his collections firm have taken a different tack to combat the problem. Most of Baxter Bailey’s successful collections come from securing payment for ripped-off carriers directly from shippers or consignees, or a lead broker on a load with co-brokers. With any luck, that ensures those parties think two and three times about dealing with that broker – or any similarly situated – again.

Next in this series: Highway robbery: Ask the tough questions during negotiations to root out the crooks