Tank owner-operators believe theirs is the best specialty. Most say they couldn’t earn elsewhere what they make on the typically fewer miles they run in liquid bulk. The physical workload isn’t too demanding.

“You’re not backing up to docks – you don’t have to physically move your own freight,” says Eric Hanson, recruiting manager with Jackson, Miss.-based Miller Transporters, which hauls chemicals nationwide. “It’s very scheduled in terms of pickups and deliveries – very rarely will they have to load and unload something by themselves.”

And even if you do, says operator Steven “Buck” Landry, hauling for FAS Environmental Services of Pierre Part, La., the physical work usually involves nothing more than “hooking hoses.”

The work can be solitary. Landry often vacuums excess fluid from injection wells in Louisiana and Texas and hauls it away for disposal. “There isn’t a soul around most of these wells,” he says. If you’re delivering to a union plant, “nobody wants to be around when you’re unloading,” given potential liability for a spill.

Rather, the truck stop perception – that tanking is dangerous, difficult, not for the faint of heart – is often simply not true. Operators in the niche find a professionalism uncommon in other applications and, when rates are as good as they are today, the possibility of making a very good living.

Pay and other perks

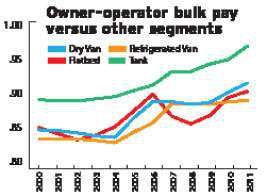

Bulk tank pay is generally higher than van and flatbed, says Kentucky-based Rick Gaskill, hauling for a small fleet leased to Quality Carriers. Most bulk tank carriers pay drivers a percentage of the gross, meaning a “guaranteed raise when rates go up.”

“I don’t have to run my tail off, that’s the best part,” says Chris Adamson, leased to Miller Transporters at its Mobile, Ala., terminal. “You’re not killing yourself to run to make a living. It’s a lot easier than van or flatbed in that respect, though a lot of people make it seem to be harder.”

Last year, Adamson ran 103,000 miles for gross revenue of $189,000 and a net $86,000, what he calls an average year, up from 2009’s relatively low $60,000 net. With miles picking up further and his truck paid off as of January, he expects to pocket a good $25,000 more in 2011.

Percentage pay equitably distributes carrier revenue between contracted owner-operators and the back office, as rates vary widely, depending on the commodity, says Usher Transport Safety Vice President Mike Baker, based in Louisville, Ky. “There’s such a diversity in tank in the products we haul. You may haul a load of motor oil out that pays $2.40 a mile… On the way back, you may have a chemical that pays $3.85.”

Usher-leased owner-operator Jim Schlise hauls mostly motor oil and related products outbound from Louisville, where he lives, and typically deadheads back. Because he usually top-loads more of the same or compatible product, he rarely has to deal with post-unload tank washes. Plus, he says, “I stay within a 500-600-mile radius. I’m usually only out about two nights a week.”

Schlise, who drives a 1990 Peterbilt 379, was named the Kentucky Motor Transport Association’s Driver of the Year, after earning Usher’s annual award in 2010. “It’s a customer service business,” he says, where relationships with shippers and receivers are more professional than in other areas of trucking.

“The customers are almost always happy to see us,” says Ray Lawson, leased to Langer Transport. That’s because consignees aren’t merely ordering product to fill inventory, says owner-operator Helen Johnston, leased to Dana Transport. “They often need that truck overnight so they can keep their production going.”

“The people who unload us are nicer, smarter people,” Lawson says. “You don’t put just anybody unloading a trailer where a mistake could open you up to a million-dollar liability.”

How the costs are spread

Carriers cover many of the owner-operator’s ancillary costs, says Lawson. “Usually, the things that the company is responsible for are the trailers and the washes.”

Tank haulers must watch their speed on curves to avoid situations such as this one, where a slight road grade makes a turn even more precarious.

Tank haulers must watch their speed on curves to avoid situations such as this one, where a slight road grade makes a turn even more precarious.Unless you’re hauling only one type of product, most liquid loads will require a washout at a carrier terminal facility’s tank wash or an independently operated wash, which starts at around $125. “It could need a cold, hot or acid wash,” Lawson says. The “heel,” any product left behind on the tank walls while unloading, must also be disposed of, typically paid for by the carrier.

Owner-operators looking to lease with a chemical or food-grade liquid bulk company will need a hazmat endorsement, as well as a Transportation Workers Identification Credential Card, which costs $135 and is required to enter port facilities. The TWIC card requires individual application and background checks similar to what haulers testing for the hazmat endorsement already undergo. Critics say it’s unnecessary redundancy, but Hanson notes that within a certain time limit, you can use a single background check for both the hazmat endorsement application (or renewal) as well as the TWIC card.

Adamson says many chemical plants require drivers to present the card. “All chemical plants are supposed to be requiring it within a year or so,” he says. You can pre-enroll in the program online via twicprogram.tsa.dhs.gov, providing identification documents to begin the process.

“Our guys are required to have at least two years’ over-the-road experience, and they have to have the hazmat endorsement and a TWIC card. And we need drivers right now.”

— Mike Baker, Usher Transport safety and HR vice president

For a video with owner-operator Jim Schlise, leased to Usher Transport, about his career with the liquid bulk carrier, check out the video section on OverdriveOnline.com.

For a video with owner-operator Jim Schlise, leased to Usher Transport, about his career with the liquid bulk carrier, check out the video section on OverdriveOnline.com.It’s uncommon for liquid bulk owner-operators to own the trailers they pull, but they often pay for extra equipment. For a PTO-driven pump, auxiliary air compressor, hoses and fittings, in addition to heat-in-transit connections to the tractor’s cooling system, Lawson says he spent around $10,000 to outfit his tractor. He runs with both a compressor and a pump, but some operators can get by with one or the other. You may lose some loads if you’re lacking in a particular area, as flammable products cannot be unloaded with an air compressor but must be pumped off, says Johnston, who doesn’t run with a pump on her 2003 Peterbilt 379.

A few leased carriers or shippers with dedicated independent tank fleets pay owner-operators hourly rates, says Steven “Buck” Landry. “I know three chemical companies that do it, and they all pretty much have a waiting list to get on.” Landry was paid $70 per hour, in addition to other pay perks, by Premier Chemical until an accident that wasn’t his fault put his custom truck (pictured) in limbo with the insurance company. Others are Sochem Solutions and his current employer, FAS Environmental Services.

A few leased carriers or shippers with dedicated independent tank fleets pay owner-operators hourly rates, says Steven “Buck” Landry. “I know three chemical companies that do it, and they all pretty much have a waiting list to get on.” Landry was paid $70 per hour, in addition to other pay perks, by Premier Chemical until an accident that wasn’t his fault put his custom truck (pictured) in limbo with the insurance company. Others are Sochem Solutions and his current employer, FAS Environmental Services.Miller’s startup package for owner-operators includes leasing all accessories needed. When Adamson signed on with the company, it paid for outfitting his 2004 International 9900 Eagle, which he recently finished paying off in the company’s lease-purchase program. Miller’s equipment doesn’t include a separate air compressor for airing off loads, says Hanson. “Some companies use a separate compressor. We use the air compressor on the tractor itself – it goes through an air filter/dryer system, then hooks to the trailer to air it up.”

At Usher Transport, Baker says a gear-driven pump will run the owner-operator “a couple thousand for the pump, the PTO and the labor put in.” Add “a couple thousand in fittings” and other costs to get started, he says.

Though it’s been many years since he rigged his 1990 Peterbilt 379 for chemical tank hauling, Schlise says he paid around $800 for his pump and a couple hundred more for the PTO that drives it. His two-cylinder Quincy air compressor cost about the same as the pump.

Owner-operator per-mile average pay for tank operations, even factoring in more deadheading, exceeds that for van, reefer and flatbed, according to the National Transportation Institute’s annual Survey of Driver Wages. Over 11 years, tank pay rose 7 cents per mile, as opposed to 5 or 6 cents in the other applications. Additionally, tank operators escaped the stagnant or falling pay that affected other applications during the recession, says Gordon Klemp, NTI principal. Miller Transporters’ Eric Hanson says that, since mid-2010, tank freight rates and volumes have been increasing.

Owner-operator per-mile average pay for tank operations, even factoring in more deadheading, exceeds that for van, reefer and flatbed, according to the National Transportation Institute’s annual Survey of Driver Wages. Over 11 years, tank pay rose 7 cents per mile, as opposed to 5 or 6 cents in the other applications. Additionally, tank operators escaped the stagnant or falling pay that affected other applications during the recession, says Gordon Klemp, NTI principal. Miller Transporters’ Eric Hanson says that, since mid-2010, tank freight rates and volumes have been increasing.Baker and Hanson say they’re actively looking for owner-operators to join their fleets. Tank experience is not a prerequisite. Hanson says, “Most of the guys we get in here come from outside the tank industry.” He says after they get some experience, many say they wish they had moved to tank years ago.

The challenge of shifting freight

Unless you’re hauling a fuel-type compartmentalized tank, your 7,000-9,000-gal. trailer is likely to be a single compartment, which demands keen attention while driving.

Illustrating the sloshing effect that can occur in a tank on the road, Helen Johnston uses a partially filled pop bottle. “Put it on its side and slant it a little, then turn it back,” she says. The movement that occurs demonstrates what happens to liquid in a single-compartment trailer.

“That load’s not worth your life – if you need to stop and take a couple-hour nap, do it. Some companies are just pushing and pushing the drivers. That’s why there are rollovers in tankers: It’s because safety isn’t put first.”

“That load’s not worth your life – if you need to stop and take a couple-hour nap, do it. Some companies are just pushing and pushing the drivers. That’s why there are rollovers in tankers: It’s because safety isn’t put first.”“During the winter,” Johnston says, “if it gets a little bit slick, you have to be careful up hills, as all the weight moves off your drives to the trailer tandems. Going down a hill, downshifting is crucial,” as the liquid will naturally put greater downward force on your rig, “pushing” it downhill.

“We have to take curves slow,” says owner-operator Ray Lawson. “If you see us on a ramp or coming into a curve, we’re usually going below the posted speed.”

The heavier the product, the slower Lawson goes. “A lot of truckers won’t worry with looking at the speedometer for curves and turns, but we don’t ever take a curve without looking at the speedometer. It’s too easy to misjudge — you have to know exactly what your speed is.”

Tanker safety on Alaska’s Haul Road

Think dealing with the weight of liquid bulk on paved highways in the Rockies sounds like a challenge? Imagine it on the unpaved Dalton Highway, or “Haul Road,” in Alaska. The road was the site of early “Ice Road Trucker” episodes, which dramatized the danger of its sharp hills and curves, especially in winter.

The Haul Road is ice-free in summer, but constant rutting of the road takes a heavy toll on equipment.

The Haul Road is ice-free in summer, but constant rutting of the road takes a heavy toll on equipment.The bulk drivers with Carlile Transportation, one of the major Haul Road carriers, are “the most professional group of guys that I’ve worked with,” says Bulk Operations Manager Jason Klein. “They’re taking care of their equipment all the time; it’s their bread and butter.”

They make good money, says Klein, with relaxed hours of service limits that enable accumulation of many more miles than your average lower-48 hauler. “Minimum three to four years of Haul Road experience is required. There are 11 percent grades — it’s a different animal.”

Pulling 9,300-gallon tanks, loaded, they run heavy at 104,000 pounds, Klein says. “Working for the oil companies, everything is based on safety — if you have an accident or a spill, you can lose your contracts.” Last year, he adds, the company moved more than 21 million bulk gallons accident- and injury-free.

ONLINE

For examples of what it can take to get into tank with your own authority — and your own tank trailer — check out Todd Dills’ Channel 19 blog from the second week in November for profiles of two Midwest independents hauling tank freight to farm and feedlot: overdriveonline.com/channel19.