The Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association’s March 29-filed legal brief against FMCSA’s electronic logging device (ELD) mandate puts a lot of weight on language in the statute that required the production of the rule in the first place. That language was included in the 2012 MAP-21 highway bill and noted by Overdrive here on the Channel 19 blog at the time of its passage into law by both Houses with the President’s signature. Specifically, MAP-21 defined electronic logging device (ELD) as a device “capable of recording a driver’s hours of service and duty status accurately and automatically.”

At the time of MAP-21’s release, North Carolina-based owner-operator William McKelvie pointed out the obvious problem with that definition, referring as it does essentially to a device that, in the current market for ELDs, doesn’t exist. Such a narrow definition leaves out any recognition of the operator’s involvement in telling such a device what exactly he/she is doing when the vehicle stops moving.

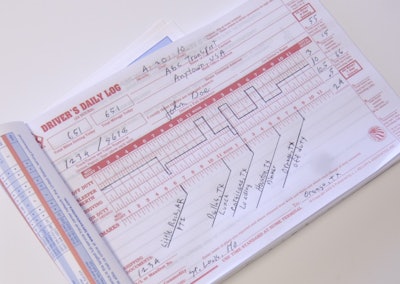

In my view, that distinction between off-duty, sleeper berth and on-duty not-driving lines in any driver’s log book may always be entirely up to the operator’s input, at least for the foreseeable future, incapable of being “automatically” recorded by an ELD or something else without significant change in the hours of service rules themselves. Regulators and advocates, meanwhile, aren’t clamoring to, say, remove the non-driving duty status distinctions, that’s sure.

At once, there is a problem with taking automatically so literally, and that’s the fact that the MAP-21 highway bill’s “electronic logging device” definition language was lifted directly from the current regulatory definition of an automatic on-board recording device (AOBRD), codified in 49 Code of Federal Regulations 395.2 since the 1980s.

Those definitions state an AOBRD is “an electric, electronic, electromechanical, or mechanical device capable of recording driver’s duty status information accurately and automatically as required by §395.15.” As I wrote in 2012, by referring to the 395.15 regulation in the definition, regulators effectively limit what “automatically” means by elaborating on device specs elsewhere and assuming driver input within “automatically.” (AOBRDs, encompassing most every engine-connected e-log on the market today, don’t automatically distinguish between non-driving lines in the log — i.e., they’re not very automatic either.)

When the MAP-21 language came down in 2012, asked whether the definition of ELDs as “automatic” recorders of duty status presented an opening for opponents of the mandate, Norita Taylor of OOIDA noted that “what happens is that [ELD] proponents and [FMCSA] appear to be quite satisfied with the limitation of what is considered ‘automatic.’ It just doesn’t seem to matter to them.”

For ELD proponents, it becomes easy to point to how much of the rest of the world has been filled with so-called “automatic” things, and that an ELD “should be another ‘automatic’ to add on to the list of automatic things in our lives,” Taylor said, “regardless of how automatic it really is.”

Calling an ELD’s operation automatic then just adds more fuel to the fire of the previously mentioned safety-cure-all misconception that has driven the industry to where it is today — staring down an ELD mandate.

OOIDA finds itself in the interesting position of arguing that FMCSA’s mandate does not conform to the Congressional statute because the rule’s device specs don’t far enough toward automatic recording of non-driving time. It has hung a great deal of its argument against ELDs in court on the point, though not the entirety of the argument by any means. Minnesota-based Truckers Justice Center attorney Paul Taylor calls the particular section of the brief at issue “the most persuasive part of OOIDA’s brief. The legal writing is outstanding. I think it is undeniable that the rule makes no provision for automatic recording of non-driving time.”

You can download the entirety of OOIDA’s ELD legal brief via this link.

“FMCSA punted on this,” attorney Taylor continues, by asserting just what OOIDA contends on the bottom of page 11 of the brief, that Congress “could not have meant what it said,” in effect, given the privacy/Fourth Amendment issues raised by the constant monitoring that would seem to be required to automatically record a duty status other than on-duty driving.

In commentary accompanying the final rule, FMCSA states plainly that it views Congress’ related supporting documents requirements as underpinning its view (that Congress means not what it says). “Supporting documents serve a critical role in monitoring a driver’s [on-duty not-driving] time,” FMCSA wrote. “Had Congress envisioned that the ELD could automatically track every duty status, it would have simply eliminated the need for supporting documents.”

But Taylor also points to the bedrock question of whether FMCSA is really improving hours compliance by mandating ELDs as perhaps the biggest one raised by OOIDA’s legal brief. “Whether the rule meets the statutory requirement to improve compliance: That is the crux of the case,” Taylor says. “It certainly improves it as to actual driving time directly, and indirectly with respect to 14-hour and 10-hour [berth] rule compliance — a little.”

As for the question of “automatic” recording of non-driving time and just what Congress meant with its statute, the Court is the final arbiter of what Congress meant with its statute, not FMCSA, attorney Taylor notes.

“I think that the Court of Appeals, at oral argument, may focus in questioning on what kind of technology is available (or possible) to monitor non-driving activity without violating personal privacy rights,” Taylor says. “If I was a judge I would pose those questions to all parties. For example, can sensors be put in the bunk to monitor the presence and length of sleeper berth time?

“The Court is ultimately the adjudicator of what Congress meant. However, if there is any ambiguity in the statute, FMCSA’s interpretation applies unless arbitrary, capricious, contrary to law or manifestly unreasonable.”

Whether the court will agree with OOIDA or with expected arguments from FMCSA as the association’s suit goes forward is anybody’s guess. FMCSA referred all requests for comment on timing of its response to OOIDA’s brief to the Department of Justice, whose Public Affairs office did not respond to my inquiries as of this writing. Norita Taylor of OOIDA notes a May 12 deadline for the U.S. DOT’s response to OOIDA’s arguments. Stay tuned. (UPDATE 4/27/2016 — Norita Taylor reports that the deadline for FMCSA’s response has changed to May 31.)

Look for further reporting on OOIDA’s challenge to the ELD mandate in the coming weeks.