Working with CCJ and RigDig Business Intelligence, a division of Overdrive publisher Randall-Reilly Business Media, we analyzed inspection and scoring data for CSA’s first two years. Here we offer insights into enforcement patterns and what you can do to keep your business in the clear. Find further “Inconsistent enforcement” installments via this page in the coming weeks. For the next installment, an analysis of how carriers’ updates to data under their control can help CSA scores, see the story published March 18, 2013.

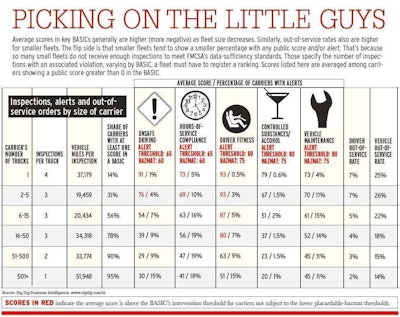

Working with CCJ and RigDig Business Intelligence, a division of Overdrive publisher Randall-Reilly Business Media, we analyzed inspection and scoring data for CSA’s first two years. Here we offer insights into enforcement patterns and what you can do to keep your business in the clear. Find further “Inconsistent enforcement” installments via this page in the coming weeks. For the next installment, an analysis of how carriers’ updates to data under their control can help CSA scores, see the story published March 18, 2013.The truck of an independent owner-operator is four times as likely to get inspected as a truck running under the authority of carriers with more than 500 trucks, according to inspection data from the first two years of the Compliance Safety Accountability program. The likelihood of being placed out of service is three and a half times as great for independent drivers – and almost twice as likely for their vehicles – compared to those of the biggest fleets.

The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration insists that its system is not biased against any carriers. Any apparent disparities are not flaws, but simply a reflection of how CSA is structured, the agency says.

One factor in the skewed enforcement actions against small operators is CSA scoring. Smaller carriers showing public BASIC (Behavioral Analysis and Safety Improvement Category) percentile rankings on average receive negative (high) scores. At the same time, because most of the smallest carriers have no public score, the average score for all of them together is abnormally low.

Click through the image for comprehensive data on rates of inspections, out of service orders and CSA BASIC percentile rankings organized according to carrier size.

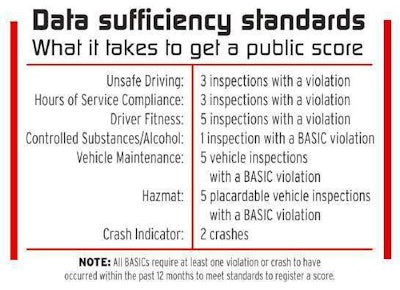

Click through the image for comprehensive data on rates of inspections, out of service orders and CSA BASIC percentile rankings organized according to carrier size.Of close to 470,000 carriers with U.S. Department of Transportation operating authority, less than half have any data in the CSA Safety Measurement System, according to recent estimates by Dave Kraft of Qualcomm. Just less than a quarter have a few inspections, but no SMS ranking or “score” in any BASIC.

In fact, more than two years after its advent, CSA has failed to produce a single public score for 80 percent of carriers with operating authority. About 90,000 carriers, or 20 percent, have at least one BASIC ranking; that’s an improvement over the 12 percent – as determined by Commercial Carrier Journal – that was cited widely in the program’s early days.

| Private scores, alerts and interventions Carriers’ scores are public with the exception of those in the Crash Indicator and Hazardous Materials BASICs. The Hazmat BASIC is new since December; FMCSA plans to make it public when the year is up.The Crash Indicator remains private given widespread concerns that it doesn’t take into account crash fault and could present a misleading safety picture to the public, though FMCSA insists its private rankings remain their most reliable indicator of true crash risk among the BASICs.Of the 20 percent of carriers with a public ranking, more than half are at alert status, represented by an alert symbol in the “BASIC status” column on any carrier’s SMS profile. Most carriers reach BASIC alert status after one of their percentile rankings rises above that BASIC’s intervention threshold. However, it is possible for a carrier to be at alert status in a BASIC without showing a public percentile ranking due to the presence of what FMCSA calls “serious violations” on record. Any alert status marks a carrier for routine investigative action via one of the agency’s intervention options. |

Given their higher exposure with so many trucks, the largest carriers are from two to 30 times more likely on average than single-truck independents to have a score above an intervention threshold, depending on the BASIC.

While FMCSA believes its system is fair, the ASECTT (Alliance for Safe, Efficient and Competitive Truck Transportation) coalition of trade associations, carriers, brokers, shippers and other service providers that has taken the agency to federal court believes otherwise. They argue that the system, amplified by FMCSA’s guidance on what the scores mean, puts all carriers – and small carriers disproportionately so – unfairly at risk, as shippers and brokers use the scores as de facto safety ratings.

The agency denies that CSA’s SMS constitutes a safety rating and washes its hands of how the data is treated in the real world. “SMS quantifies the on-road safety performance of motor carriers so that FMCSA can prioritize them for intervention,” says spokesman Duane DeBruyne. “Use of the SMS for purposes other than those identified may produce unintended results and inaccurate conclusions.”

The system’s varied results stem from how it works, FMCSA says. Larger carriers, with a much larger number of inspections and violations in total, easily exceed the minimum threshold for scoring. So the percentage of carriers with alerts in the BASICs is in line with normal expectations for such a percentile-ranking system.

On the smallest carriers’ side, the opposite is true. Just one out of 10 companies with five or fewer trucks has “a score above one of our thresholds,” said a senior FMCSA official in January. Any carrier that fails to meet the “data sufficiency standards” – varying numbers of inspections with an associated violation within two years – in any BASIC does not receive a public score there.

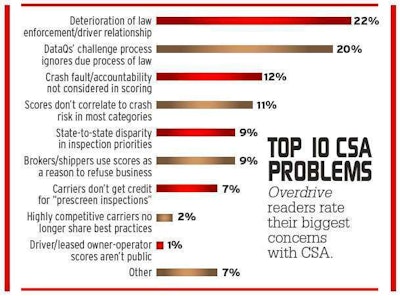

For carriers large and small, this irregularity can sting in different ways. It has become a problem in efforts to secure freight from brokers and shippers, which in January almost 10 percent of Overdrive readers called the No. 1 problem with CSA (see “Top 10 CSA problems” chart below).

“As a small carrier, and I have seen this firsthand, just a few minor violations can send a score skyrocketing, putting the carrier nearly out of business as it becomes evident no one will employ your services because the system shows you are a risk, even though you operate safely.”

“As a small carrier, and I have seen this firsthand, just a few minor violations can send a score skyrocketing, putting the carrier nearly out of business as it becomes evident no one will employ your services because the system shows you are a risk, even though you operate safely.”–Daniel Miranda, testifying before the U.S. House of Representatives’ Small Business Committee in July 2012

“FMCSA urges shippers and brokers to use carriers who have been inspected versus those who have not been inspected,” Miranda says. “Moreover, brokers and shippers feel as if they will be liable if they do not use carriers with positive CSA rankings, something only achievable if a carrier undergoes lots of clean inspections. As a small carrier, I am less likely to be inspected. … It is difficult for me to show a score, much less” a positive score.

That’s only part of the dilemma. If the independent does pass a sufficiency threshold, the carrier is likely to start its publicly scored history above the intervention threshold in that BASIC. Consider the average ranking for single-truck businesses actually scored in each of the BASICs; all except the Vehicle Maintenance and Controlled Substances/Alcohol BASICs show average rankings above the intervention threshold.

In January, Overdrive polled readers on some of the biggest problems with CSA.

In January, Overdrive polled readers on some of the biggest problems with CSA.You don’t have to look far to find examples of carriers with fewer than 15 trucks that make their CSA scoring debut at the highest level possible, 99.9, after a single inspection with a violation or two meets data-sufficiency requirements in a BASIC. This makes for no shortage of difficulty in score management.

“If the system is displaying ‘less than 5 inspections with a violation’ or ‘less than 3 inspections with a violation’ ” in any BASIC, FMCSA says, “it doesn’t mean that they might not be on the ‘cusp’ of generating sufficient negative information for us to assign a high percentile score and intervene.”

|

Drill down into the data – just one click from your main carrier SMS results page – to “see how many inspections with violations that they do have and what those violations are,” FMCSA says. Then, “take efforts to avoid similar violations.”

Five-truck intermodal fleet owner Thomas Blake experienced this dynamic. He spent more than a year above the alert threshold in the Hours of Service Compliance BASIC. Now he’s back to showing no score on his main SMS profile there. It went from showing a ranking in the 60s – close to the intervention threshold – to being below data sufficiency standard levels because he had less than three inspections with a violation.

What did it take to get there? He did what a large majority of large carriers have done – invested in electronic logging. Blake, who at the time had six trucks, spent $9,000 for an eLogs system. It eliminated minor “form and manner violations,” putting his operation a leg up in the Hours BASIC over his peers.

The only way to improve scores other than getting clean inspections is to wait. The time-weight value of inspections and violations in scoring falls after six months and again after 12 months. They drop out of the SMS after two years.

It’s not uncommon for a small carrier or independent to have an unlucky rash of inspections with violations that meet data sufficiency standards. In such a case, two years saddled with a score above the intervention threshold can be a long time indeed. Without clean inspections or any new violations, some carriers even have seen scores go up over time as their number of inspections in the system decreases, placing them in a different safety-event peer group for comparison.

Installing electronic logs, a costly decision that seemingly would please inspectors and improve an independent’s score, in a sense backfired on Blake in the short term but paid off eventually. Because so many inspectors view a driver with eLogs as not worth the time of an inspection, it was unlikely that Blake’s trucks actually would get clean driver inspections to improve his score quickly. With time, however, Blake’s Hours of Service Compliance score disappeared.

The business impact of this and other scoring scenarios is what’s driving the ASECTT case against FMCSA, likewise the ongoing data-quality audit by DOT’s inspector general. The suit primarily seeks relief from agency “encouragement” of broker and shipper communities to use CSA scoring data in business decisions until the data quality issues are shored up and a rulemaking process for a new Safety Fitness Determination is finished. The SFD would allow use of CSA data to rate carrier safety as an absolute value.

The suit alleges FMCSA has gone beyond its mandate to reduce crashes by providing the systems’ rankings to the public and offering guides on their use in areas like carrier selection.

It “wasn’t until recently that there was any consequence to having a high score” in one of the BASICs, says Tom Dickmeyer, chief executive officer of the Cline Wood insurance agency. Today, as brokers get “a lot more pressure with regard to lawsuits coming back on them for the acts of motor carriers that they’ve used, they’re getting much more diligent about who they go with.” Meanwhile, some shippers “won’t entrust their loads to you … if you have high scores or a couple of alerts,” Dickmeyer says.

Insurance companies also are paying more attention to CSA. Plaintiff’s attorneys have succeeded in using concepts of negligent entrustment and vicarious liability against carriers, brokers and shippers to get larger settlements to suits that involved carriers with CSA BASIC alerts, Dickmeyer says. In general, the less expertise of the insurance company and/or its underwriters in trucking, the “heavier weight CSA is going to get” in the underwriting process due to ease of access to the public system, he says.

While the lawsuit threatens to push CSA in one direction, FMCSA is pushing it the opposite way. A Notice of Proposed Rulemaking to make the CSA SMS the basis for a safe/unsafe-to-use final determination is expected this year. If no changes are made in the data sufficiency standards and other scoring issues, it could become more difficult for many independents and small carriers to win business.