An older dry van with basic specs can be bought for around $10,000. Some newer ones can go into the upper-$30,000 range.

An older dry van with basic specs can be bought for around $10,000. Some newer ones can go into the upper-$30,000 range.After testing the waters of independence, Rich Rukstalis in 2011 returned to Landstar as a leased owner-operator, hauling dry van loads and transitioning away from working the spot market as a reefer hauler.

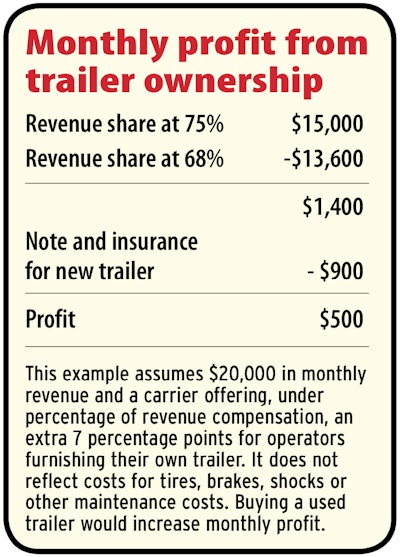

A year into his stint with Landstar, he had a revelation. “I looked at the numbers, and I said, ‘Now wait a minute. If I had my own trailer, I could get an extra 7%,’ ” he says of the percent-

age of revenue rate that Landstar pays its owner-operators. That is, Rukstalis could score 72% of Landstar’s paid rate rather than the 65% he was earn- ing. “Why should I give them the 7%?” he asked himself then.

Not long after, he was the proud owner of a new 2012 Great Dane dry van trailer, which he bought for $30,000. His insurance and payment on the five-year loan totaled $800 a month, but it enabled him to earn an extra $1,200 to $1,300 a month, he says, netting him as much as $500 extra in income.

Such higher percentage offers for trailer ownership are standard fare at many carriers — even smaller ones. For owner-operators willing to make the investment and handle the maintenance costs, stronger profits could follow, as well as ownership of a major asset that generally lasts longer than a tractor and requires less maintenance.

Owner-operators can “go from earning about 68% to 72% if you’re truck-only to getting about 75 to 80% if you have your own trailer,” says Todd Amen, president for ATBS.

If a dry van load pays the carrier $2 a mile, for example, and an owner-operator was paid 70% of that, they would earn $1.40 a mile. But with a trailer acquisition and a percentage of 75%, for example, the per-mile rate bumps up to $1.50. On an 800-mile trip, that’s $80 extra.

Leased dry van owner-operators at ATBS averaged 9,050 miles a month last year. An extra dime per mile would earn them an additional $905 in revenue per month, based on the example above.

For a three-year loan on a new trailer purchase, monthly payments and insurance might be $800 to $900, meaning owner-operators in that scenario initially would roughly break even. A used trailer purchase with a payment of only $400 to $500 a month would add $400 to $500 to that revenue.

New dry vans run about $36,000 to $39,000 at Interstate Trailer Sales in Fontana, California, says sales representative Pat Gibbons. With 10% down on a three-year term, payments would be $800 to $900, he says.

However, earning potential jumps after the equipment is paid off, and should last for years. “You’re going to get about 15 years out of them,” says Gibbons. Well-kept trailers can last even longer.

Don Ake, an FTR economist who tracks equipment pricing, pegs the price of a new dry van around $32,000, though that varies widely with specs and add-ons.

Used trailers, with lower payments, offer more profit immediately. That was the route taken by Debra Desiderato, an independent owner-operator and former Landstar contractor.

Landstar operator Rich Rukstalis has been happy with the return on his investment since he bought this 2012 Great Dane dry van new.

Landstar operator Rich Rukstalis has been happy with the return on his investment since he bought this 2012 Great Dane dry van new.She bought her first trailer for $10,000 in 2015 from another owner-operator. Desiderato saw the 2002 Great Dane dry van as a step toward becoming an independent, and the extra 7% in revenue helped her save for that transition. “It’s pretty much a no-brainer,” she says.

She paid cash for the trailer and then spent another $1,500 for wheel bearings, seals and other maintenance. She didn’t run as many miles as other owner-operators, but still earned an extra $500 a month from Landstar.

Interstate’s Gibbons says his dealership’s used offerings start around $6,000 for a dry van trailer, though those have base specs and are 15 to 20 years old. Trailers with air ride suspension, for instance, will cost more. The company has 2009-model trailers for roughly $17,000, he says. “They’re pretty much ready to roll.”

Jimmy Navarez, owner of small fleet Angus Transportation of Chino, California, says he buys used trailers – outfitted with aerodynamic equipment such as wheel covers, tails, skirts and tire inflation systems – for about $16,000. Those are about eight years old, but “they look and sound like a new one,” he says.

Navarez offers his three owner-operators an extra 5% if they provide their own trailer, but none of them have taken him up on the offer yet.

Upfront costs aside, trailer maintenance is generally cheap and easy, especially compared to tractor upkeep.

“There’s not a whole lot” that goes into trailers in terms of upkeep and expenses, says Desiderato. “Wheels and brakes — that’s pretty much it. Compared to a truck, maintenance on a trailer is nothing. As long as the doors open and close.”

Likewise, Rukstalis says his 2012 Great Dane has required minimal maintenance. “I’m on my second set of shocks, my second set of brakes, and I’ve put two sets of tires on it. Other than that, I wash it once a week or once every other week.”

Finally, changes in the federal tax also make a trailer purchase attractive. The Internal Revenue Service is offering sweet incentives for equipment purchases through 2022. Under the tax overhaul enacted in 2017, owner-operators can deduct 100% of equipment purchases in the year they make the purchase, rather than hav- ing to phase the deduction over years.

An owner-operator purchasing a $36,000 trailer could deduct the whole amount from their taxable income. A deduction of that size would cut tax liability substantially or even wipe it out for a low earner with other deductions. The equipment depreciation bonus also applies to used equipment.

Key considerations before buying

While the profit potential in owning your own trailer can be compelling, the ownership also can be limiting. With a dry van acquisition, for example, an owner-operator could lose access to reefer and flatbed loads.

Also, “You can forget about drop and hook,” says Rich Rukstalis, who’s leased to Landstar. “That’s an option you lose.”

That could negate some revenue gains, says Todd Amen, president of financial services provider ATBS. “You get locked into live load and unload,” he says. “I think that’s the biggest consideration.”

Operators who buy a trailer also should pick a segment where they’re confident they can turn

a profit. If you’re used to dry van hauling, don’t try to switch to flatbed or auto-hauling simply because of anecdotes. “People get enamored when they hear great stories,” Amen says. “You can’t just look at what your buddy has done the last six months. You have to take a long- term view and make sure it’s a risk you can take.”

Part of that risk is timing. A new independent could have trouble finding dedicated shippers in a cooling market. But as far as an independent or a leased operator buying a trailer, a market such as the present one, coming off a boom period, can yield good deals on used equipment.

“People are selling off because they’re not making it,” says independent Debra Desiderato. “I’d try to find somebody who was struggling and trying not to get their equipment repo’d” and buy from them.