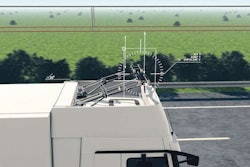

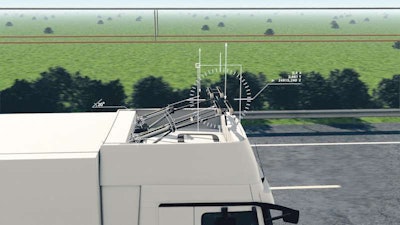

The prong-shaped pantograph wand relay system makes contact with the power lines and acts as a conduit for the electrical power flowing from the lines and directly to the vehicle’s electric motor.

The prong-shaped pantograph wand relay system makes contact with the power lines and acts as a conduit for the electrical power flowing from the lines and directly to the vehicle’s electric motor.The abundant supply of natural gas in the United States has been driving the demand for alternative-fuel trucks. What’s also showing some promise, though in limited applications, is the all-electric truck.

FedEx and UPS are experimenting with all-electric vans in urban applications. These vans already are used in Europe.

The main concern in the United States is the relatively short range of the vehicles. On the other hand, the vans consume no fossil fuels and produce no emissions – particularly attractive benefits in smog-plagued cities such as Los Angeles or Houston.

If a driver needs to pass a slower truck in the eHighway lane, the system automatically disconnects from the power grid, and the prong-shaped pantograph wand lowers. The system automatically re-engages the power grid when the driver returns to the eHighway lane.

If a driver needs to pass a slower truck in the eHighway lane, the system automatically disconnects from the power grid, and the prong-shaped pantograph wand lowers. The system automatically re-engages the power grid when the driver returns to the eHighway lane.Now experiments in Germany and California with another type of electric truck could lead to a radically new way for trucks as heavy as Class 8 to move freight in the United States.

The Siemens company, a longtime leader in railroad technology, is rethinking many of its proven rail concepts with an eye toward a highly efficient low-emissions commercial vehicle.

Siemens, based in Munich, Germany, feels its sophisticated eHighway Project has the potential to succeed in what would be dedicated eHighway corridors in the United States.

At the heart of the concept is a diesel-electric hybrid truck. Unlike existing hybrid trucks in the states, this vehicle uses a constant-state diesel engine to drive a high torque-output electric motor – the same principle used to drive diesel-electric locomotives around the world.

In this mode, the Siemens hybrid drive system allows the truck to behave much like a conventional diesel truck: The driver can maneuver on freeways and in urban surroundings as he would in any truck.

The benefit comes when the vehicle pulls into a dedicated “eHighway” lane that features overhead electrical lines powered by substations. The technology is common on trains in some European and Asian cities.

Once the truck is in an eHighway lane, a monitoring sensor in the truck’s nose detects the overhead power lines and automatically deploys a prong-shaped wand, called a pantograph. This acts as a conduit for the electrical power to flow to the electric motor.

[youtube 6qChp3r6gb8 nolink]

Holger Sommer, eHighway project manager for Siemens, says the company decided from the outset that its concept would have to share eHighway lanes with conventional truck traffic. That’s partly because building exclusive electric truck lanes would be too expensive.

The pantograph not only moves up and down to make connection with the power lines, it also can move side-to-side to maintain contact and counteract normal steering input from the driver. Most importantly, the system is highly flexible: Trucks are not stuck in position as if they were on a slot car track. The driver also retains full control of all braking functions.

Any kinetic energy generated by a truck connected to the wires is put back into the grid automatically, where it can be used by other trucks.

If the sensor in the truck’s nose is not functioning, the driver can disengage the system manually with the push of a button.

Since the vehicle essentially is an electric truck with a constant-rate diesel engine, it can produce immediate high torque outputs without fuel consumption spikes. Lower-displacement diesel engines power the trucks and run continuously in their most efficient modes, drastically reducing fuel costs and dramatically cutting vehicle emissions, Sommer says.

Siemens has been testing the system extensively in Europe with modified Mercedes-Benz Actros trucks. Preliminary work has begun on building lanes in California to test the system for use in the United States.

The plan is to develop a one-mile stretch near the Port of Long Beach. The cost is $14 million, for which the California Air Resources Board is seeking funding. In addition to validating the eHighway concept in real-world conditions, the tests also will seek to determine vehicle and infrastructure costs.

Siemens stresses that the overall infrastructure impact in terms of investment and construction is relatively minimal, and that the system can be installed easily on existing roads. However, the Los Angeles Times estimated it would cost $5 million to $7 million a mile to convert roads to eHighway use.