A week or two back I had a conversation with the Ireland-based CEO of the company Tracknstop, which pitches itself as a tool not only to help prevent truck and/or cargo theft, but to stop it in its tracks when it happens, as you’ll see in the video above.

Declan O’Mahoney, said CEO, pitches the electronic device, which has been recently patented in the U.S. and is in trials with some fleets, in the context of international terrorists’ willingness to use large vehicles as weapons, which has of course happened in devastating fashion in Europe in recent years with larger-class trucks and here in the U.S. with a lighter rental unit.

“We have millions of miles in Europe now,” O’Mahoney says, where Tracknstop is commercially available already. “There’s a lot of tracking companies who can tell you where the truck is and … all sorts of other things” about its operating status. “That’s kind of standard, mature technology, and there’s a lot of players in that space.” (At once, it’s hardly universal — just more than half of owner-operators in Overdrive‘s audience via this ongoing poll have thus far reported utilizing some form of tracking occasionally or frequently.)

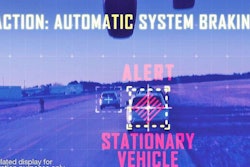

What Tracknstop and a few other providers (such as the Magtec company) can do that most can’t is allow a remote operator to halt the vehicle when suspicious activity is suspected or detected.

Find more about the Tracknstop company via this link to its website.

Find more about the Tracknstop company via this link to its website.Tracknstop, O’Mahoney adds, will “coexist with existing” vehicle tracking solutions on-board, many of which are offered in tandem with electronic logging devices at this point for fleets large and small. Installed covertly, the Tracknstop device when activated slowly cuts off the fuel supply to the engine, essentially. As shown in the video at the top, in the event of a false-positive of sorts — a stopped vehicle that is not in fact in danger — once the driver communicates with law enforcement and/or the control center, the device is also capable of allowing restart remotely as well.

And it “goes further than that,” says O’Mahoney, who notes Tracknstop can utilize electronically geofenced areas to safeguard vehicles during particular times of day. He uses the hypothetical example of a bus yard in New York City where vehicles are housed and not scheduled to be utilized at particular times of day — say, overnight. “We can geofence that yard, and if somebody breaks in there and decides to go joy-riding,” once the bus is “driven through the gate, it shuts down within 15 seconds down the road.”

The company’s also got the capability of doing the opposite, preventing a Tracknstop-outfitted vehicle from entering a geofenced area — say, during law-enforcement-sensitive events like the New York City marathon or inauguration festivities in Washington, D.C., he says. “We can give the capacity to a trucking company to geofence that entire area.” He extends that example to a company hauling jet fuel or another explosive commodity. “If I owned that trucking company, I could say to my drivers, ‘law enforcement doesn’t want any trucking in Manhattan. If you drive into there, the truck will shut down and you’ll be fired.'”

It’s perhaps yet another way, he says, to provide a little more security to control risk, something owners might pitch to customers to “differentiate from the competition and potentially reduce your insurance costs.”

Such tech could be a game changer for cargo and tractor theft, too, with a wide uptake in use of new ability for individual truck owners and fleets to hand law enforcement on a silver platter, so to speak, exactly what they need to pursue a theft, provided owners are awake at the switch and attentive to potentially active thefts.

Assuming affordability of such a service, would it be something that would interest you?

O’Mahoney wouldn’t specify costs, noting only that it will “depend on the size of the fleet,” as in so many things of course. “Installation,” he says, “is more complicated than your standard tracker,” though it’s not a particularly difficult process and can be done by a skilled mechanic in a half-hour to an hour. There are both hardware costs and monthly connection fees as well, he adds.

Trials are ongoing in the U.S. with companies hauling sensitive commodities like ammunition and hazmat loads. “We’re looking to target them first,” O’Mahoney says.

Oil boom in Midland, Texas

Looks like opportunity is knocking in the oil field again — or still knocks, as the case may be. Intrastate Texas work remains outside the ELD mandate for now, it’s worth noting …

Reason I mention it is that over the weekend, I came across this Friday piece of reporting in the L.A. Times that led with an interview with the mayor of Midland, Texas, about local government employment, or the difficulties therein given everybody in town seemed to be making bank around the booming shale-oil activity in the Permian Basin. It contained a nugget of a quote from one Steve Sauceda, who, as the Times reported, “runs the workforce training program at New Mexico Junior College.”

As Sauceda told writer David Wethe: “A CDL is a golden ticket around here.”

The story went on to quote a 30-year-old flatbed hauler who said he might make as much as $140K this year.

Any bulk or flat haulers seeing similar in oil field-related work this year?