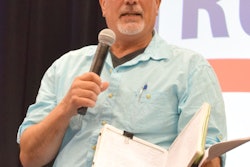

From left: ATBS’ Matt Amen, Godspeed Expediters small fleet owner Les Willis, Henry Albert of Albert Transport, and Angus Transportation owner-op Jimmy Nevarez

From left: ATBS’ Matt Amen, Godspeed Expediters small fleet owner Les Willis, Henry Albert of Albert Transport, and Angus Transportation owner-op Jimmy NevarezSmall Fed-Ex Custom Critical-leased fleet owner Les Willis cracked wise during the Friday, August 23, panel discussion that was part of the Overdrive/ATBS Partners in Business seminar series at the Great American Trucking Show. As a wise sage once told Willis (fellow expediter Bob Caffee to be exact), “If you want to make a million dollars in a truck, start with $2 million.”

His ultimate point: Profit can be hard-won in the trucking business, though with diligence around business analysis and cash flow, cost control, freight market wisdom and customer relationships, an independent owner-operator or small fleet owner can set themselves up for long-term success.

Joining Willis (four trucks) in the panel discussion, moderated by ATBS’ Matt Amen, were well-known independent Henry Albert (one truck) and Jimmy Nevarez, a four-truck small fleet owner specializing in local and super-regional runs around his Southern California home base with brokered freight and leasing owner-operators.

Overdrive’s Partners in Business is sponsored by TBS Factoring Service.

Overdrive’s Partners in Business is sponsored by TBS Factoring Service.Albert, too, has small fleet experience in his past, and he recalled the day he went out and got his authority, starting with one truck in the 1990s. Business plan intact, appropriate insurance on file, a customer lined up, plenty of money stashed away in anticipation of the unavoidable payment delays he knew he’d experience when he started moving freight, he’d been assured by federal representatives of speedy handling of his authority application.

Yet the days went by, turning into a week, turning into more than a month. Waiting for the filing to go through “ate up all my [cash] reserves,” he said, after which he turned to what he said was ultimately $60K worth in credit on multiple credit cards in those early days, not that he had to use all of it. Planning to specialize along lanes between Charlotte, N.C., and Philadelphia (“Nobody in the Carolinas wants to go to Philly,” he said), then, his first load outbound from Charlotte was cancelled on him by the broker.

“Brand-new truck, brand-new flatbed,” a brokered load that cancelled but “a return load set from a customer that was direct,” Albert said. After the cancellation, “I sat around [Charlotte] all day” looking for another load to Philadelphia before, nearing the end of that, he resolved: “I’m not canceling myself on my first load” with the customer. Rolling down the road toward Philadelphia burning fuel put on a Discover Card he has to this day and doesn’t use any longer, “I kept looking at my empty flatbed and thinking, ‘What the heck have I done?'”

His short-term cash-flow remedy, however unsustainable relying on credit cards is long-term, proved an effective method of demonstrating dependability to that direct customer. He got to the customer early, ultimately, and explaining the situation of his cancelled brokered load to personnel there, his contact told him he could have just called to explain the situation. “I said, ‘One day that will happen,'” but he wasn’t about to cancel his first direct load.

Nevarez’ cash-flow strategy today is tied inextricably to the nature of the freight carried in his local/regional operation. “When I started adding trucks,” he said, he found himself on occasion “creating two-invoices a day, per-truck. On top of that I still drive one of my trucks.” After driving all day, “the last thing I want to do is hunt down payments and nonpayments.”

Nevarez turned to factoring, starting with a company that was bought out by TBS Factoring Service, who also happens to have been the sponsor of the Partners in Business seminar series and updated business manual the last couple years. “They provide me a service level that’s not just factoring,” Nevarez said. “It’s like a complete back-office for me,” a non-recourse arrangement for immediate payment upon transmission of invoices, bills of lading and rate contracts. It’s a solution to the problem of mounting back-office tasks for the four-truck manager that avoids “having to hire a full-time employee for that specific job.”

Nevarez’ Freightliner Team Run Smart / Angus Transportation 2018 Cascadia and 2010 Wabash Duraplate van took 2nd in the First Show – Combo class in Overdrive‘s Pride & Polish this year at GATS.

Nevarez’ Freightliner Team Run Smart / Angus Transportation 2018 Cascadia and 2010 Wabash Duraplate van took 2nd in the First Show – Combo class in Overdrive‘s Pride & Polish this year at GATS.ATBS’ Amen noted his organization’s guidance to owner-operators as they start adding trucks. “We typically tell them the sweet spot is 5 to 15 trucks — somewhere in there you’ll need somebody on-site doing the day-to-day tax accounting and operations. That happens somewhere in that spot,” at which point ATBS’ tax and business services are no longer necessarily a good fit for them.

“It’ll reach that point, eventually, when I get out of the truck,” Nevarez said, looking ahead to the future. “I’ll be that full-time employee.” Until then, factoring fills the need, for a small percentage of each invoice. “I know all [factoring companies] are not created equal. [You have to] find the right one to work with you and take care of you when you need help.”

Les Willis’ principal customer is the fleet his four reefer expedited units are leased to, thus some of those back-office needs, particularly around customer invoicing, aren’t much of a consideration. Yet he’s diligent in cash-flow-related areas like maintenance and repair reserves, to keep himself ahead of the cost-benefit curve as the equipment ages. He stresses the need for close cost accounting and analysis on a per-truck basis, separating routine, interval-based preventive maintenance costs and repair costs to give a clearer picture of how the equipment is holding up.

“In my process, maintenance and repairs have their own categories,” he said. “When I start to see repair accounts dwindling down, that throws a red flag up to

At once, Albert added, don’t overdo it on maintenance, particularly with some of the newer trucks. “It used to be a big deal to get to 500,000 miles without major engine work. Then came a million, and one up above that,” he said. “If you’re above 7 miles to the gallon, the factory recommended oil change is at 70,000 miles” for some trucks, though conventional wisdom about 15,000-mile intervals is still common among owner-operators.

He gave a small example from his own operation — “I replaced my air filter every six months,” for little other reason than it looked dirty, Albert said.

His mechanic asked a pertinent question: “Where in the world are you running that you need to change that often?”

“Go by your restriction gauge” to know whether it’s doing its job right, Albert said. “I’ve gotten 250,000 miles out of an air filter that I was just throwing money away at before.”