As part of its ongoing research into the lifecycle emissions of diesel-powered trucks compared to alternative-fuel trucks, the American Transportation Research Institute last week released a new report on the viability of renewable diesel (RD) fuel as a way to cut carbon emissions in the industry with minimal impacts on operations.

The new report looks at RD as an alternative to both traditional diesel fuel and battery-electric (BEV) trucks; the impacts of using RD on the environment, operations and its financial implications; and how the use of RD could be increased in trucking. Download the full report here.

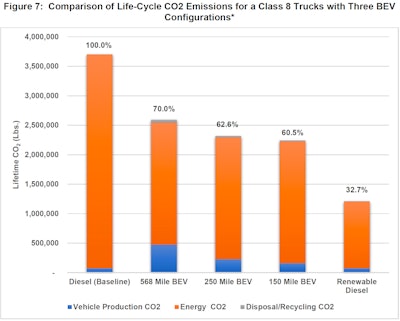

Jeff Short, ATRI vice president, said previous research conducted by the group found that renewable diesel “looked a lot better” than battery-electric when considering the full lifecycle emissions, which includes mining for minerals for batteries, production of the trucks, use of the trucks, and recycling/disposal of the trucks. That study found a potential 30% decrease in life-cycle CO2 emissions of a BEV compared to a internal combustion engine truck using diesel, and a 67.3% decrease using renewable diesel in existing Class 8 trucks.

ATRI's research found an internal combustion engine using renewable diesel to be cleaner over the full lifecycle of the vehicle than battery-electric trucks.Charts courtesy of ATRI

ATRI's research found an internal combustion engine using renewable diesel to be cleaner over the full lifecycle of the vehicle than battery-electric trucks.Charts courtesy of ATRI

The great thing for truck owners about renewable diesel, Short said, is it’s chemically identical to petroleum diesel, so no engine or equipment modifications are needed to existing diesel trucks. This makes it viable for long-haul, over-the-road operations, while BEVs are limited by range, weight and more.

“It’s absolutely identical to the diesel made out of crude oil that comes out of the ground,” he said. “It can be mixed in with petroleum diesel in any amount, or it can be used as a standalone.”

Bill Aboudi, the owner of 10-truck AB Trucking based in Oakland, California, said he’s currently using renewable diesel in his operation at the ports. He said he’s seen no change in his trucks since going to renewable seven years ago. He also experimented with biodiesel in the past -- an alternative fuel that’s chemically different from petroleum diesel that can be blended to use in existing diesel engines.

He said with biodiesel, “the only thing I experienced when switching from regular diesel to biodiesel was I had to be ready to change the filters out. It cleaned up the system really well," early on flushing out build-up caused by diesel fuel. Because of that, "the filters would clog up. As soon as [one] filled up with gunk, I replaced it. After a few months, we were fine.”

Since his trucks had already been using biodiesel when he switched to renewable, he wasn’t able to tell if the same would happen with the filters on switching straight from petroleum diesel to RD. He did note, however, that he bought some used trucks recently “and didn’t experience any filter clogging” with RD.

California, of course, is leading the charge toward “zero-emission” trucks, with a particular push toward battery-electric since it’s the most readily available truck with no tailpipe emissions. The state was planning to ban new diesel trucks from registering to operate at the ports at the beginning of 2024, but that mandate is on hold, for now.

[Related: Do fleets need to comply with California's now-halted diesel ban?]

Aboudi said, however, that the state “is not taking steps up the ladder, they’re jumping straight to the top of the building.” With renewable diesel, “if it helps not only because it’s renewable but it cuts down on particulate matter, these are the baby steps we need,” he added.

Short noted that fleets he’s talked to on the West Coast that use exclusively renewable diesel “have less soot, for instance. Thus, they have fewer maintenance requirements that they have to take care of because it’s burning cleaner.”

RD vs. BEV: Environmental impacts

ATRI's analysis looked at both the environmental and operational impacts of RD compared to battery-electric trucks.

Environmentally, ATRI’s research found that when comparing a 150- or 250-mile BEV -- which are currently available today -- to an internal combustion engine using renewable diesel, the RD truck has 29.9% lower life-cycle CO2 emissions than the 250-mile BEV, and 27.8% lower life-cycle emissions than the 150-mile BEV.

“It’s a completely different level that RD is able to reach,” Short said. “Generally, when you look at everything, you can say RD has at least 50% lower emissions that BEV, assuming BEV could actually do the job today’s diesel truck could do. But they’re not doing that kind of distance.”

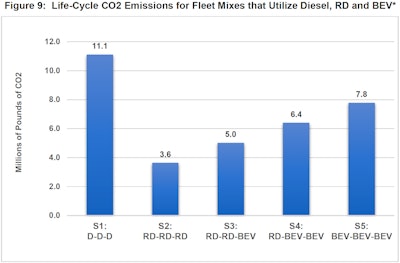

ATRI also looked at a hypothetical fleet of three trucks, offering five scenarios for life-cycle emissions:

- Scenario 1: All three trucks run strictly on petroleum diesel, with total life cycle CO2 emissions of 11.1 million pounds.

- Scenario 2: All three trucks exclusively use renewable diesel. No technical modifications to the trucks are needed, and life-cycle CO2 emissions decrease to 3.6 million pounds.

- Scenarios 3-5: The three RD trucks are replaced incrementally with BEV trucks over a period of time. This increases life-cycle CO2 emissions incrementally, ultimately reaching 7.8 million pounds of CO2 for three BEV trucks.

“The shift from RD to BEVs is going to create harm,” Short said.

Using renewable diesel in all three trucks resulted in lower life-cycle emissions for a fleet than transitioning to BEV trucks, ATRI found.

Using renewable diesel in all three trucks resulted in lower life-cycle emissions for a fleet than transitioning to BEV trucks, ATRI found.

While CO2 is a big factor in emissions reduction, regulators are also looking to reduce air pollutants, such as particulate matter (PM) and NOx, which come from the tailpipe. This is often the biggest reason cited for moving to BEV trucks, because they have no tailpipe emissions.

That is the case, yet ATRI noted that those pollutants are released during vehicle production along the supply chain, typically in other countries. Based on ATRI’s research, producing a BEV truck results in NOx emissions that are nearly 10 times higher than producing an diesel truck and PM emissions 7.5 times higher.

RD vs. BEV: Operational considerations

Looking at the operational benefits, the results are clear-cut, Short said. “There is no change” with RD operations. “It does the same thing. It can go as far as it used to be able to go” with petroleum diesel.

Mileage is one big limitation to BEVs currently, in addition to a lack of charging infrastructure nationwide. Currently-available Class 8 BEVs can go between 150-250 miles between charges, while a diesel truck, with or without RD, can go over 1,000 miles between fuel-ups. ATRI found that 77% of Class 8 trucks in the for-hire trucking industry drove more than 250 miles a day on average in 2022.

Another use case for RD over BEV is in the weight of the trucks. ATRI’s report states that one Class 8 BEV currently on the market weights 4,000 pounds more than its diesel counterpart, yet can only travel 230 miles per charge. Even with the Federal Highway Administration’s 2,000-additional-pound allowance for BEV trucks, this truck is still losing 2,000 pounds of cargo capacity.

In previous research, ATRI modeled a Class 8 BEV sleeper truck with trip ranges of 500 miles or more between charges, and that truck weighed 13,800 pounds more than a diesel truck.

“The added weight, whether it is 4,000 pounds or 13,800 pounds, will impact the amount of revenue weight a BEV truck can haul,” ATRI said in its report. “The conundrum is that the heavier the truck battery, the longer and farther the truck can drive; but with larger batteries the truck can carry less revenue-generating cargo.”

[Related: Analysis: California not ready for its own EV mandates]

RD vs. BEV: Cost comparison

According to a Department of Energy analysis in 2022 looking at the cost differences between a BEV and ICE Class 8 long-haul truck, the BEV truck analyzed had an up-front purchase cost of $457,000, while a comparable diesel truck had a cost of $160,000 -- a nearly $300,000 difference.

[Related: CARB's new small-fleet electric truck finance effort]

Fuel costs are another consideration. Diesel prices depend on the price of crude oil globally, which are impacted by geopolitics and more.

Electricity prices are generally regulated by public utility commissions, of which there are more than 3,000 across the country. Electricity prices have also been on the rise across the U.S. in recent years. In large cities, ATRI said electricity costs have increased 29.1% since January 2020.

“Unlike diesel prices, electricity prices may vary considerably by time-of-day and day-of-week, adding further uncertainty to costs for trucking,” ATRI said. “For trucking, these prices may also have additional demand charges to cover the cost of extending electricity infrastructure.”

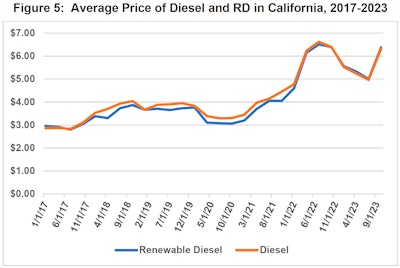

Renewable diesel is still an emerging fuel type, but ATRI said feedstock prices will be the determining factor in RD prices. Subsidies currently play a role in RD prices. In California, RD prices are almost identical to petroleum diesel prices because the RD price is subsidized by California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard carbon credit program.

The price of renewable diesel has almost directly mirrored that of petroleum diesel in California since 2017, due in part to subsidies and credit programs ongoing.

The price of renewable diesel has almost directly mirrored that of petroleum diesel in California since 2017, due in part to subsidies and credit programs ongoing.

[Related: Electric-truck purchase incentives present big challenges for small fleets, owner-operators]

Renewable diesel is made from feedstocks of vegetable or animal products, such as vegetable oil, animal fat, and used cooking oil.

ATRI’s research found that large trucks consumed about 36.12 billion gallons of petroleum diesel fuel in 2023. The U.S. as a whole consumed about 2.8 billion gallons of RD last year -- a 67% increase over 2022. The California Air Resources Board reported that 73% of RD consumed in the U.S. was sold in California.

At the beginning of 2023, the U.S. had 17 RD plants in 11 states with a production capacity of 3 billion gallons per year. ATRI also found that U.S. production capacity of RD increased nearly 280% in the two years from January 2021, when there were only six plants in the U.S., to January 2023.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration forecasts that domestic RD capacity will again more than double between the end of 2022 and the end of 2025, from 2.6 billion gallons per year to 5.9 billion gallons per year. The University of Illinois has also forecasted that RD production capacity will increase to 7.4 billion gallons per year after 2025. ATRI’s report noted that some diesel refineries are converting to RD refineries, further increasing capacity.

“This is happening today, not sometime in the future,” Short said. “This isn’t building new power plants,” like what will be needed for a full transition to battery-electric trucks. “There’s the conversion of refineries, but that’s a much lower barrier to moving forward with this compared to building new power plants, putting up new transmission lines, or installing hundreds of thousands of truck chargers across the country.”

Short said that the 3 billion gallons of RD currently produced in the U.S., if it were all used in long-haul trucking, would be enough to power 296,000 trucks for an entire year.

[Related: Will battery-electric trucks end up a ‘black eye’ on environmental benefits?]