- An overlooked clause in President Donald Trump's executive order mandating English language proficiency might end up having a greater impact than ELP enforcement or reviewing CDLs for non-citizens.

- Truck Safety Coalition's Executive Director told Overdrive about direct experiences with non-English speaking drivers causing tragic crashes and how to fix the safety crisis.

- Ultimately, the entire CDL credentialing process in the U.S. needs an overhaul, as revealed by recent high-profile cash-for-CDL schemes.

- TSC supports mandating drivers take the CDL tests in the state of their domicile and a minimum behind-the-wheel training hours requirement.

In the whirlwind of activity that followed President Donald Trump's executive order mandating English language proficiency and a nationwide "audit" of CDL issuance to non-citizens, there's one small subsection that some believe might hold the key to improving safety and fairness across the industry.

Zach Cahalan, Executive Director of the Truck Safety Coalition, said he's seen the worst of the worst when it comes to bad drivers and tragic accidents.

"The Truck Safety Coalition is America’s leading victim-centered non-profit for victims of large truck crashes and survivors of those crashes," he said. "We help people with grief counseling with peer support, and, for those who want to, we help them tell their story."

Those stories from crash victims and survivors "inform and put a face to the numbers" of crash statistics, he added. TSC lobbies the government for better safety in trucking. "We get those stories out in front of the media, regulators and policy makers to try to reduce the incidence of truck crashes."

In that vein, he's seen firsthand the safety impacts of drivers who don't know the language or rules of the road.

[Related: Meeting an out-of-service, non-citizen driver who can't read English]

"I can’t give you a hard number, but we have multiple victims and volunteers who have lost a loved one to a driver who couldn’t speak English whatsoever," he said. Those drivers "need a translator in court and needed a translator" at the scene of the crash. "It leaves these victims with questions that aren’t ever really going to be answered -- Did that driver understand the road signs? Were they properly tested? Those are just things they're never going to know."

However, it doesn't have to be that way.

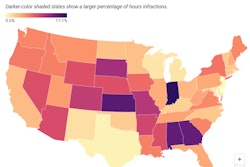

On the topic of ELP and safety, Overdrive has tried to survey and measure the population of drivers who can't speak English. A majority of Overdrive readers in a recent survey pegged the number at more than 15%, while a 2023 FMCSA study put it at 3.8%. Furthermore, a recent Overdrive analysis found motor carriers with ELP violations broadly tended to crash at nearly double the national average.

[Related: Overdrive reporting reveals at least 60,000 active non-domiciled CDLs]

But "there is very little that can be said with certainty" about the impact of English speaking and safety, said Cahalan. Indeed while Overdrive has tried to establish some baseline facts around ELP and safety, so far the data merely implies a correlation at the carrier level and is not yet strong enough to outright prove direct causation at any individual driver level.

Echoing what Overdrive heard from carriers in its survey of ELP and trucking, Cahalan said "by no means is the ability to speak English the determining factor if you’re a good, sufficient operator" of commercial trucks.

What's a much better indicator? Training.

“In the opinion of TSC, it is the quality of the training, experience of the driver operating behind the wheel of a large truck, and knowledge of and adherence to Federal Motor Carrier Safety Regulations, such as hours of service and vehicle maintenance, that are far more reliable and predictive indicators of a truck driver’s likelihood to drive safely," according to a TSC statement following Trump's ELP mandate executive order.

Ultimately, Cahalan and TSC support the return of ELP to the out-of-service criteria, but plenty of fluent English speakers drive dangerously too, in the organization's view.

"Drivers must be able to speak English sufficiently to converse with others in the supply chain and understand the road signs, particularly in long haul trucking," said Cahalan. With all the different variables on the open road, "you want to know that whoever is driving that truck has been sufficiently trained to handle" adverse weather, terrain and traffic and roadwork disruptions, "and that it's not just an open question" if they're trained or not.

Rather than after-the-fact efforts to distinguish good CDL holders from bad, "the time to answer that question is before a CDL was ever issued," said Cahalan.

Cahalan, again, isn't alone in drawing the line as to who should, or shouldn't be allowed to drive, along basic training lines. One commenter on Overdrive's recent survey wrote: "Any CDL school should ensure that drivers can meet all regulations. It should start there."

Even CDL schools themselves have sounded the alarm, calling out the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration for not addressing the "threat" posed by "unscrupulous training entities."

FMCSA allows training providers to self-certify that they meet federal requirements, and each state has its own rules for issuing CDLs. Some states, like California, do not even track the citizenship status of CDL holders and will issue CDLs to applicants that don't even give their full names.

Cahalan pointed to recent cash-for-CDLs scandals in Oregon and Florida as evidence of rot in the current CDL credentialing system in the U.S.

"We believe strongly you need to take [the CDL skills test] in your state of domicile," said Cahalan, who said bad actors go "forum shopping" to find the easiest CDL schools, sometimes across state lines.

Cahalan said "word gets out quickly in the underground network" about fraudulent CDL schools, allowing more bad drivers in the industry.

Since prior reporting about CDL schools' letter to FMCSA urging action against bad schools in the training-provider registry, the agency has removed some training providers from the approved registry, but Overdrive found many of those schools hadn't been in the CDL training business for years.

"I think you’re going to see the same thing that Oregon saw in a lot of places -- CDL mills and pay to play schemes," said Cahalan. "There are hubs fraudulently issuing CDLs. That's something that's more or less out in the open and obvious."

That's where Trump's executive order comes into play.

Below mention of the ELP requirements, right under the non-domiciled CDL audit, Section 4(b) of the order instructs DOT to "evaluate and take appropriate actions to improve the effectiveness of current protocols for verifying the authenticity and validity of both domestic and international commercial driving credentials."

Notice how that section applies to all CDL credentialing, not just the type available to non-citizens.

Cahalan would like to see a minimum behind-the-wheel-hours requirement for CDL applicants, which many in the trucking community have supported in past. In 2017, 8 in 10 Overdrive readers supported minimum hours of behind-the-wheel instruction as part of the entry level training rule, which ultimately wasn't included.

Cahalan would also like to see law enforcement investigate CDL schools that graduate drivers who display dangerous ignorance or disregard for safety. "Let’s set people up for success, not just do what’s the quickest way we can move product from point A to point B," he said.

Importantly, Cahalan pointed out, there are hardworking drivers of all races and ethnicities in the U.S. A lot of talk about race and language can become "noise," he said, in the quest to actually button down the nation's CDL credentialing process and make the roads safer.

"Driving a truck is hard and challenging work. TSC wants to be sure everyone has had the necessary training to do so safely," he concluded.