Michigan-based Eagle Express small fleet owner Leander Richmond got a bit of a DataQs victory last year, but it didn’t come easily. Richmond was using the system in a common way — disputing what to him was an officer’s obvious misinterpretation of safety regulation. In this case, it was a driver charged at roadside in Michigan with violating the federal cell-phone-use statute.

Like Richmond, many owner-operators and small-fleet owners report having used the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration’s DataQs system. Administered in cooperation with state enforcement jurisdictions, DataQs is the principal protocol for carriers, drivers and others to challenge or simply correct information collected about them -- crash information, inspections and their associated violations, chiefly.

In Richmond’s case, no citation for cell-phone use was issued, and the driver was not utilizing the phone for anything other than GPS at the time of the stop, as the officer’s examination of the phone revealed, Richmond said. The federal prohibition on handheld device use does not include GPS purposes, as Richmond pointed out, but rather handheld use while talking or texting, among other types of uses.

Richmond’s first attempt to challenge the violation dragged on for more than eight months. His goal was to have it removed from his company’s and the driver’s records in the Compliance, Safety, Accountability and Pre-Employment Screening Program systems. Richmond’s description of his frustrating efforts is of a piece with other horror stories around challenging violations.

Michigan-based Eagle Express owner Leander Richmond knew his driver, charged with violating a federal cell phone use regulation but not issued a citation, was in compliance. Working through the DataQs system, Richmond spent months attempting to correct the record.

Michigan-based Eagle Express owner Leander Richmond knew his driver, charged with violating a federal cell phone use regulation but not issued a citation, was in compliance. Working through the DataQs system, Richmond spent months attempting to correct the record.

Thousands of DataQs reviews are rejected each year. Many come from requestors who have a reasonable basis for challenging and who have exercised persistence in what can become a months-long project. Rejections are common in cases that boil down to a judgment call, where the carrier or driver lacks evidence to change the mind of the officer who wrote the violation and will eventually weigh in again on the request for data review (RDR), then yet again if there is an appeal.

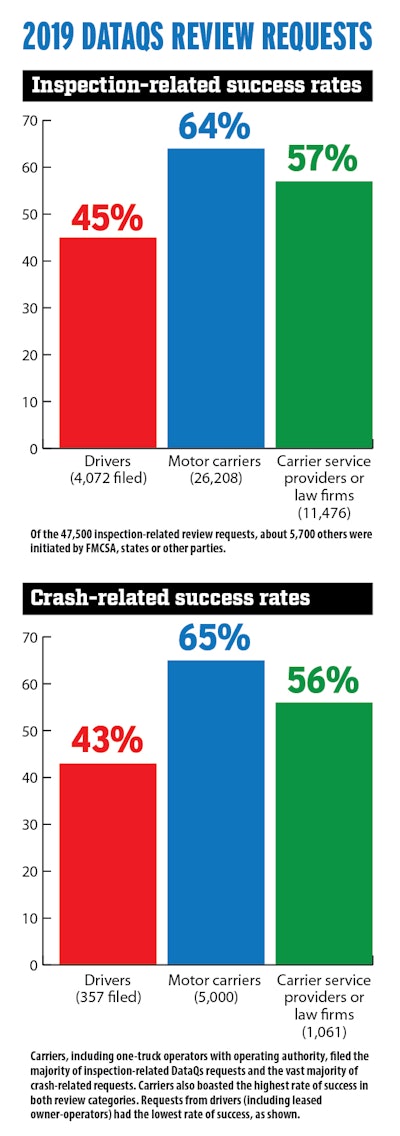

Perhaps the cases most maddening to fleet executives and owner-operators, though, involve matter-of-fact correction of basic data about a truck, a driver or a carrier that gets stonewalled even when the review request presents clear evidence of the error. In 2019, according to federal data, there were 22,271 such informational-type DataQs filed – inspections/crashes assigned to the wrong carrier or driver, for instance, duplicate records in the system, and more – accounting for 41% of the total 54,000-plus DataQs filed that year.

In its defense, FMCSA and state partners point to thousands of DataQs filings per year where such information is, in fact, quickly corrected. The average success rate – meaning information was changed or removed as a result -- of this category of informational-type DataQs was 78% in 2019.

For DataQs overall, success rates ranged widely when grouped by carrier size. On the low end, fleets of two to five trucks had a success rate of 51% for inspection-related DataQs in 2019. One-truck owner-operators, accountable only for themselves, had a comparable rate of 62%. For 500-plus-truck fleets, with personnel devoted to tasks such as DataQs filing, that rate was 69%.

Though it’s not hard to find prolonged DataQs cases, FMCSA touts its processing time for RDRs. It says most are closed within days of its “best practice” target of “within 14 days of receipt.”

Nevertheless, even with clear evidence that objective information was recorded in error, fixing that can be “like pulling teeth” when a filing gets rejected, said Adam Kleinschmidt, who works in the compliance department at the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association. He cited a case in Georgia where OOIDA challenged incorrect info on a carrier. The request was denied, with this response, he said: “The inspecting officer did his job at the time to verify the information.”

OOIDA obtained further evidence – an accident report – and appealed. “We verified the information on the truck equipment was not matching,” Kleinschmidt said. This time the correction was quickly approved. “They’re making us do all the heavy lifting when we try to call them out,” he said.

He and others say those kinds of filings are usually successful because other records – insurance policies, accident reports – support the claim.

On the other hand, “It’s rare to beat a violation,” Kleinschmidt said. FMCSA statistics back him up. During 2019, just 39% percent of DataQs filed seeking to change a violation that had no associated citation (a ticket that can be adjudicated in court) resulted in a change.

“Basically you’re talking to the guy who wrote the inspection, so it doesn’t do you much better than arguing on the side of the road,” Kleinschmidt contended, yet that’s not the case in all states.

In Minnesota, known for a tiered DataQs decision appeal process that involves outside industry reps, the first review does involve the inspecting officer. Yet, said Captain Jon Olsen of the state patrol, a DataQs administrator handles collection of information from the carrier/driver and the officer. With the assistance of a dedicated staff, the administrator makes the decision on any changes. In essence, that administrator’s doing at least some of the heavy lifting.

OOIDA will file an RDR as a free service for its members “as long as it’s valid,” Kleinschmidt said. “We need to make sure the information is challengeable,” meaning it has clear evidence.

Responses can vary widely by state, he said. Arizona makes a filer “jump through the hoops” to ensure that you have a position that qualifies you to make an appeal. “Kansas almost never changes anything” in his experience, “no matter how good your argument.”

Kansas Highway Patrol Public Information Officer Nick Wright notes the DataQs that come into the patrol there are changed at the rate of 40%-45% of the time, below the approximately 65% national average for 2019, according to FMCSA.

Texas-based Clark Freight Lines, with 180 trucks, has largely given up on challenging violations and now files RDRs mostly about correcting misinformation, said Vice President Danny Schnautz. “It has to have some kind of proof beyond what you normally get at roadside,” Schnautz said.

In one case still under DataQs review, a normally short-haul driver was given a no-logbook violation when discovered without an electronic logging device. But the officer failed to understand that the driver remained well under the eight days allowed beyond the short-haul radius in any rolling 30-day period before the ELD requirement kicks in.

In spite of continuing frustrations for the carrier, “These DataQs have improved exponentially from when they first started,” Schnautz said. “Almost every one was denied. We’d go back again and again and say you must not be reading my submission. The joke was they wouldn’t read them, they’d just hit ‘Denied.’”

Texas-based Clark Freight Lines, after repeated failures in appealing violations through DataQs, now focuses mainly on correcting misinformation through the program, said Vice President Danny Schnautz.

Texas-based Clark Freight Lines, after repeated failures in appealing violations through DataQs, now focuses mainly on correcting misinformation through the program, said Vice President Danny Schnautz.

In some states, it might not have been a joke. Olsen said he has heard of past automatic denial policies from colleagues in other states. “Then if you request a review, they might consider it,” or follow the common procedure of “sending it straight to the inspector” who wrote the violation or handled the inspection or crash in the first place.

In Eagle Express owner Richmond’s case, “the DataQ process failed miserably because the officers are not held to a standard other than what they believe,” he said. “This was my experience when I argued with a sergeant” over the handheld-cell-use violation. The issuing officer stood his ground on the violation, a Michigan State Police sergeant agreed, and the request for a change was denied.

“That’s not the process that needs to be in place,” noted Olsen. “It’s not doing anybody any favors.”

Another problem with fairness in the process is the issuance of a warning, such as for speeding, written at roadside also with a Level 3 inspection report where it’s marked as a speeding violation. That violation flows through to the carrier’s SMS profile and the driver’s Pre-employment Screening Program report.

A speeding warning is not a citation that can be taken to court, so if that violation is on the associated inspection report, “you can’t do anything about it,” said Drivers Legal Plan Marketing Director Richard Banks. “They should write you a ticket, but they don’t want to go to court.”

The smallest fleets, such as those represented by OOIDA and the National Association of Small Trucking Companies, can be at a disadvantage in succeeding at a DataQs filing since they often lack a department, or even one person, devoted to handling the process. “They want to verify registration, or they want insurance records, or ELD records,” Kleinschmidt said. “You really need an office to come up with a lot of this.”

Fleets the size of Payne Trucking, a 130-truck carrier based in Fredericksburg, Virginia, can afford to employ someone who specializes in this, said Christopher Haney, director of safety and human resources. “So you can’t say this is a fair program.” Haney has years of experience in this area and has never failed in a DataQs request. Small fleets “don’t have the resources to argue what they need to argue.”

With persistence, however, some get their desired result.

Eagle Express owner Richmond, for instance, who also notes the problem of having a violation listed but with no citation to open the door for a court appeal. Months into his DataQs efforts, he delivered a note to the Michigan Attorney General and copied the state police. He included the language of the applicable federal statute, his reasoning based upon that, and this language:

Not having an actual citation provides no mechanism by which this could have been handled through the court and I am not happy just accepting this as “the way it is.”

I would like to assert that mentioning the cell phone law, in the violations section, as a reason for this [stop] is as good as a guilty assessment in the CSA scoring process. If there was no violation in the stop then there should be no mention of a violation in the inspection report.

A lieutenant with the state police eventually agreed. “Another small victory,” Richmond said.

Read next: Correcting errors: How they can happen, how they hurt

More in the "Setting the Record Straight" package:

Two states, CVSA lead way in countering DataQs appeals bias

How to mount an effective DataQs challenge

Podcast: Fairness in Minnesota's DataQs appeals process