Previously in this series: Highway robbery: More warning signs in negotiations with brokers

You think you’re all set: After 120 deadhead miles, you’re almost to the pickup — when the broker calls. The load’s canceled, he says, and $150 truck-ordered-not-used (TONU) is coming your way. Like as not, say James Woods, Chad Boblett and other seasoned independents, he found somebody to do it cheaper and is lying.

It’s happened to Woods. He didn’t get the broker to admit he was lying on the phone — he just kept on going to the pickup location, talked to the shipper and watched the load being put on another truck.

Independent owner-operator James Woods

Independent owner-operator James Woods“Whenever rates get up high like they are,” says Boblett, “shippers and brokers are paying more than they were ever paying before. First and foremost, it’s OK to have the conversation about detention,” TONU and other accessorials such as unforeseen layover. The industry standard for TONU seems to be $150, he adds. If empty miles to the pickup are going to be high for you and you suspect the broker may fish for lower offers, however, bump it up.

“Say deadhead is going to be 100 miles,” Boblett says. “I’ve said my truck-ordered-not-used is $200 — even $400.” If they balk, look out for the canceled-load banana peel, should you take the freight.

It’s generally “easier to negotiate TONU than detention” in today’s market, Boblett says, and detention is getting easier to negotiate in part with growing digitalization driving some measure of rate transparency. Uber Freight last year standardized TONU ($200 plus $2/mile deadhead), detention ($75/hour after two with four maximum) and layover ($300/day) rates for loads booked within its app, and plenty traditional brokers are up-front about accessorial offerings.

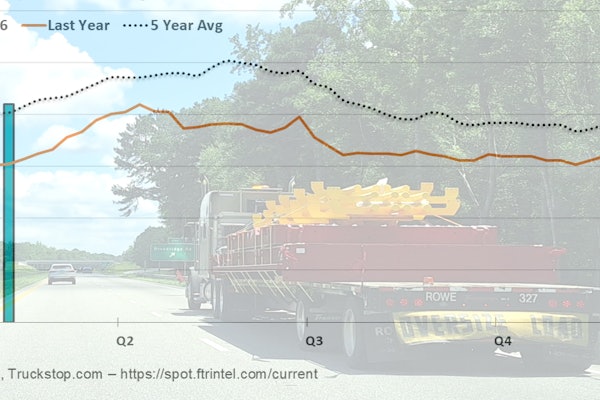

Such more-transparent “disruption” in the freight market is being welcomed by some owner-operators, but others say it doesn’t go far enough to combat a related but bigger problem of broker margins far and above what is reasonable, with owner-operators on the short end of the stick. Many operators believe the push for maximum profit, whatever the cost in toil or honesty be damned, clearly infects some corners of the brokerage world, to the detriment of those doing the real work.

One way of getting a good idea of what shippers are paying brokers is by talking directly to shippers.

“Brokers know that we will take a load to keep from sitting,” Woods says. “I’m one of the few guys who will actually get out and talk to the shippers — we know the shippers are paying $3,000 for a load of tomatoes, for instance, and the broker comes to us and says, ‘Man, all I’ve got in it is $1,900.’ Ask one for a rate sheet or transparency now, and you know what they’ll tell you? ‘You have a good day, sir.’ ”

Amid the fuel shock and precipitous falloff in business in 2008 and surrounding years, bipartisan legislation was introduced that would have codified full pass-through of fuel surcharge monies charged to shippers to the entity responsible for buying the fuel. Most importantly, the TRUCC Act, as it was known, also would have required disclosure to the fuel-cost-bearer “a written list that specifically identifies any freight charge, brokerage fee or commission, fuel surcharge or adjustment, and any other charges invoiced.” While not going all the way to full transparency, it got close.

In Overdrive reporting on this legislation that ultimately failed, it’s perhaps no wonder Robert Voltmann, head of middleman organization Transportation Intermediaries Association, howled about it amounting to a “ ‘re-regulation’ of freight transportation, in which all carrier, broker and shipper margins would be public information.”

Another measure in the TRUCC Act would have more explicitly prohibited the presentation of “false or misleading information on a document or in an oral representation about the actual rate, charge or allowance to any party to the transaction or transportation.” The “re-regulation” Voltmann bemoaned in 2008 might have gone a long way toward combating situations such as those that Woods describes.

OOIDA ended up working with TIA on the broker-bond proposal in subsequent years, which raised the $10,000 bond required of brokers to $75,000. TIA reportedly worked for an increased bond partly as a compromise that might head off “public disclosure of broker margins” becoming law.

Next in this series: Resources for broker credit checks, collections and filing against a bond