This is the third part in a three-part series on how owner-operators can work toward retirement. See the other two installments in the links below.

For owner-operators running a small fleet, the large asset they’re most experienced with buying and selling is a truck and trailer. What’s less familiar is the potentially more valuable asset of a successful independent operation.

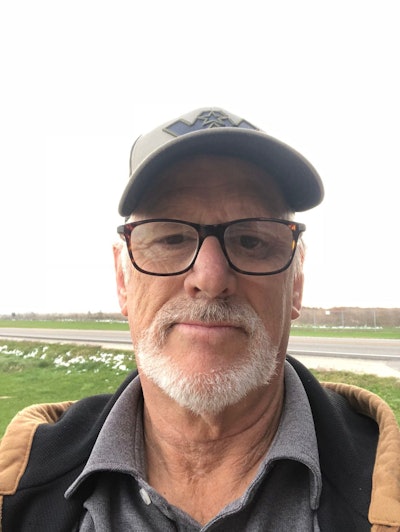

An established small fleet with loyal customers and drivers can bring a good price, making it a key asset for a retiring owner. Small-fleet owner-operator Monte Wiederhold isn’t sure how his business will fare when it comes time to sell. He drives this 2000 Western Star, which has more than 1.5 million miles.

An established small fleet with loyal customers and drivers can bring a good price, making it a key asset for a retiring owner. Small-fleet owner-operator Monte Wiederhold isn’t sure how his business will fare when it comes time to sell. He drives this 2000 Western Star, which has more than 1.5 million miles.When retirement comes knocking and it’s time to divest the business, it can mean a pleasant surprise for the owner.

“The value of the trucks is nothing compared to the value of the routes they’re driving,” says Dennis Bridges, who provides financial services for leased and independent owner-operators. “If they’re dedicated routes, that’s literally a stream of income somebody’s willing to pay very good money for.”

This would be true only for a fleet owner with operating authority, not a multi-truck owner who leases units to a large fleet, says Henry Seaton, a transportation attorney.

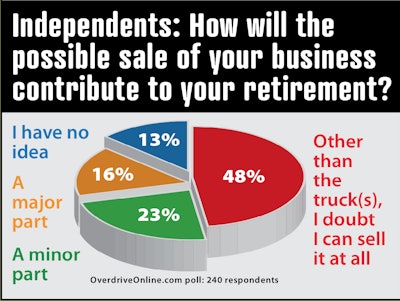

Bridges says fleet owners often “have no idea that this is actually a sellable asset, even if it is just literally one or two or three trucks.” However, not all observers are optimistic about sales prospects for the smallest of independent businesses.

The sales price for a small fleet is often 1.5 to 2 times the annual gross revenue, Bridges says. For some such sellers, “that ends up being the primary source of their retirement plan.”

A couple that owned a fleet of about 12 trucks in Georgia needed to back out of the business, expecting to sell the equipment and shut the doors, Bridges says. Instead, they “ended up selling well into seven figures,” and the business continued.

Another common formula for a sales valuation is a multiple of the seller’s EBITDA, says Seaton. That’s a common business term for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization.

Small fleet owner Monte Wiederhold

Small fleet owner Monte WiederholdThe majority of fleet sales fall into a multiple of roughly 2.75 to 3.25 times EBITDA, says Spencer Tenney, owner of the Tenney Group, which brokers sales of mid-size to large fleets.

In the smallest independent operations, such as one or two trucks, “many of them are not sellable business,” he says, because it’s simply the owner doing most or all of the work. “When a company functions more like a business and less like an owner-operator, a multiple of EBITDA is a common starting place” for valuation.

Seaton says an EBITDA multiple of four is common for bigger fleets but that sales of the smallest fleets often don’t boil down to a simple formula. One reason carriers have less interest in buying small fleets is because the transition might not be worth the trouble.

“It’s hard for them to get all the procedures in place to bring a small carrier into compliance, to teach them how to switch it over,” Seaton says. “A larger client is looking for someone with 100 trucks, not five.”

Also, any given buyer has its own special needs, he says. It might be interested in a fleet’s drivers and customers, but not the equipment or a shop, leaving the seller the chore of selling equipment and real estate.

Small fleets tend not to build up equity in real estate, says David Owen, president of the National Association of Small Trucking Companies. When they do own real estate, it can be a hindrance, such as when a fleet shop has operated at one site for many years and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency categorizes “that land useless for anything other than trucks,” Owen says.

Stable drivers are more commonly a prized asset in a sale, though early turnover is a real risk for a fleet buyer. Not only is there unknown loyalty to a new owner, but also once a sale is public knowledge, big fleets are looking to poach the stronger drivers.

Tenney refers to such a contract provision as a holdback. “Say it’s an all-cash deal, but 10 percent is held in escrow for six months until 90 percent or 80 percent of the drivers are successfully transferred to the new business,” he says.

“To a sophisticated buyer who wants it,” Seaton says, “it says basically, ‘I’m buying your goodwill and your driver list, but I can pay you more based on the loyalty of the customers and the loyalty of the drivers.’ ”

For that customer retention, a buyer might offer the seller a 6 percent commission from existing shippers’ revenue for up to a year and a half, Seaton says.

Tenney agreed that such an earn-out provision is common when the buyer needs protection from shippers’ defection. A fleet with five customers might get 90 percent of its revenue from only one of them. “That’s a pretty high risk,” he says. A buyer likely would want an earn-out clause or a substantial discount on the sales price.

Not all small-fleet buyers are big fish looking for smaller ones. Monte Wiederhold was driving one of five owner-operator trucks for B L Reever Transportation when he bought the business in 1993 from founder B.L. Reever.

“I paid $130,000 for that, which, I think, probably about half of that was money in accounts receivable,” Wiederhold says. “So I paid probably $60-$65,000 for goodwill, if you want to call it that.”

There wasn’t much more involved, given that there were no company trucks and no real estate. Three of the other four owner-operators stayed on.

The fleet, based in Maumee, Ohio, hauls mostly flatbed freight out of Toledo, Ohio. Wiederhold says in the 25 years he’s owned the company, he’s kept it at five to six trucks.

Wiederhold, 63, says he hasn’t thought seriously yet about retirement. “It would be nice to sell the business for a premium, but I’m not sure that will happen.”

Bridges says a small-fleet owner can handle a sale on his own, but it’s also common to work through a business broker, an attorney or both.

Tenney doesn’t work on small-fleet sales, but he recommends any seller “be early in the process in terms of finding out what their business is worth.” One advantage of doing so is that as the market changes, a seller “can make adjustments for wealth planning or retirement planning” and avoid an unpleasant surprise as his career ends.