This multipart series, published in early 2020, explored issues related to the financial security of freight brokers and how some shady operators exploit loopholes in current regulatory processes to cheat owner-operators, despite unenforced statutes intended to better prevent the practice.

This multipart series, published in early 2020, explored issues related to the financial security of freight brokers and how some shady operators exploit loopholes in current regulatory processes to cheat owner-operators, despite unenforced statutes intended to better prevent the practice.A congressional mandate to fix huge loopholes pertaining to the financial security of transportation brokers and freight forwarders remains mostly unfilled eight years after its passage into law.

As a result, every year owner-operators and small fleets continue to get cheated out of untold hundreds of thousands of dollars. Larger fleets are hardly immune, but being more established with shippers, employing more support personnel and often running their own brokerages, they suffer much less from broker problems.

Though a small fraction of fraudulent brokers gets punished, most are never brought to court. Many seem to easily manipulate the bonding and claims process, closing after their reputation is shot and reopening under another name.

Nonpayment issues can have stark consequences. Such was the case for Texas-based owner-operator Rob Goodwin. When he was stiffed on payment for two of three roughly $7,000 loads years ago, it triggered a cascade of financial problems.

“I filed on the broker’s bond,” Goodwin adds, and “ended up getting some money a year later on one of the loads.” But it was too little, too late. He gave up his motor carrier authority and leased to a small fleet. “You just lose,” he says.

When a broker failed to pay Rob Goodwin on two out of three loads, it triggered financial problems that led to him giving up his operating authority. Now as a leased operator, he pulls a reefer with this 2000 Western Star.

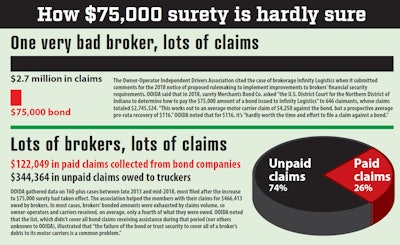

When a broker failed to pay Rob Goodwin on two out of three loads, it triggered financial problems that led to him giving up his operating authority. Now as a leased operator, he pulls a reefer with this 2000 Western Star.The most prominent intermediary-related aspect of the 2012 Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act highway bill was to boost the minimum required surety bond or trust from $10,000 to $75,000. That insurance-like backstop is intended to protect motor carriers in the event of a broker’s failure and inability to pay the carrier. Though it went into full effect the following year, it falls far short of being able to ensure that cheated operators can file a successful claim for the full value of what they’re owed.

The speed of regulatory action has been quite the opposite on other MAP-21 provisions that could significantly help put a stop to the crooks. In addition to tentative moves regulators made in 2014 toward some further action, later abandoned, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration on Sept. 27, 2018, issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking, looking for input on implementing new statutory requirements in eight MAP-21 areas. Since the ANPRM’s comment period ended Nov. 26, 2018, no action has been taken.

FMCSA Spokesman Duane DeBruyne said no determination has been made about the fate of the proposed rule. He declined to speculate when further action might come. Sources within the U.S. Department of Transportation, which oversees FMCSA, and the White House Office of Management and Budget point to each other as responsible for taking the next step.

Overdrive received no response to inquiries to the U.S. House and Senate transportation committees and their highway subcommittees regarding the unenforced provisions of MAP-21.

David Dwinell, a broker who runs loadtraining.com, a broker training program, blames FMCSA for the lingering problems and lack of attention to MAP-21. “They are not only not enforcing the law, they are ignoring it,” he says. He also says the agency was given no additional personnel as part of MAP-21 to enforce the congressional directives.

Filing a lawsuit against a broker is another option when payment is withheld, assuming the defrauded operator can identify and locate the broker. A handful of egregious cases involving various broker frauds have resulted in prison terms and six- and seven-figure penalties over the last few decades.

The courtroom route is rarely pursued because typical claims of $1,500-$2,000 don’t justify the time and expense of a lawsuit, says Daniel Larson, CEO of Pacific Financial Association, one of the largest providers of broker sureties.

In situations that do get to court, Dwinell says he has served as a witness, sometimes on behalf of the broker, other times on the other side. “If there are 100 cases of broker fraud? Three go to court,” he says. Brokers sometimes win, partly because some claims against them appear frivolous.

One of the MAP-21 provisions mandated by Congress would be crucial to quickly identifying middlemen who get into business with an intent to defraud owner-operators and fleets. That provision would give the agency new power to immediately suspend a broker’s authority as soon as claims on that broker’s bond are deemed valid by the surety provider.

The current suspension protocol predates MAP-21. It requires a bond/trust provider to give the bonded broker 30 days to replenish the security when a claims payout effectively reduces the required $75,000.

The surety provider also is required to give FMCSA 30 days’ notice of a pending cancellation of the $75,000 surety instrument. Given the increased speed of today’s trucking transactions, that’s more than enough time for crooks to continue contracting with unsuspecting shippers and carriers, with no intent of paying tens of thousands of dollars in freight bills before disappearing.

The Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association believes removing that time lag before a broker’s suspension and revocation would occur is ultimately key in making the increased bonding amount effective. In OOIDA’s public comment in response to the 2018 ANPRM, the association called immediate suspension “the most important aspect” of the eight areas identified: “It is critical that FMCSA’s Final Rule implements the imperatives and timeliness” required by Congress “by suspending a broker’s authority before the broker’s nonpayment to motor carriers results in claims on its bond or trust in an aggregate amount of more than $75,000.”

Click through the image for a larger version.

Click through the image for a larger version. Defining exactly what number or frequency of valid claim submissions should trigger a suspension or cancellation would be tricky, says Larson of Pacific Financial. The largest and usually reputable brokers get claims every day because they have so many transactions, yet they process them routinely. The vast majority of brokers, being much smaller, get few, if any claims filed, he says.

Furthermore, if legitimate brokers get suspended or canceled too abruptly, “fewer carriers would end up getting paid,” Larson says.

OOIDA also argued that some sureties seem to operate under the “fiction” that their requirements to provide notice to FMCSA of valid claims didn’t apply until they’d actually paid one. Under that assumption, “This means the broker can continue to conduct business even if there is effectively no longer any financial security in place.”

There’s evidence plenty individuals get into the brokerage business to exploit such lags in the surety claims process. No federal agencies contacted by Overdrive had precise figures to quantify the scope of outright fraud as opposed to insolvency regarding the thousands of revoked brokerage authorities in recent years. Fraudulent broker activity, though, is certainly no secret.

“We see a lot of that,” says Jennifer Licktieg, president of TBS Factoring Service. “The broker goes into business, ramps it up, then closes shop.”

When the money runs out, the broker might reopen at the same or different address, under a different name and authority.

Larson believes “broker fraud gets a lot of media attention,” but that “less than 2% of all transactions in the transportation industry could be associated with broker fraud.” For its part, PFA does extensive background checks before accepting new clients to identify suspicious data such as multiple uses of the same address or having personnel of questionable background.

When FMCSA lacks the ability or initiative to act quickly to suspend a broker’s authority upon the filing of an initial valid claim, OOIDA argues, the increased bonding amount does little to adequately protect carriers unlucky enough to get involved with a fraudulent or insolvent broker. OOIDA’s examination of 160-plus claims filed in recent years by its members showed that brokers’ sureties covered just 26% of billed freight charges. Most of those claims occurred after the $75,000 bond requirement was in place.

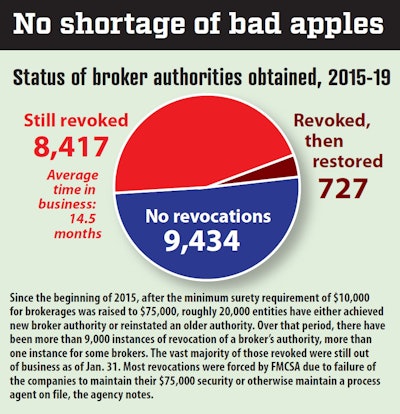

FMCSA data on brokerages filing for new or reinstated authority since 2015.

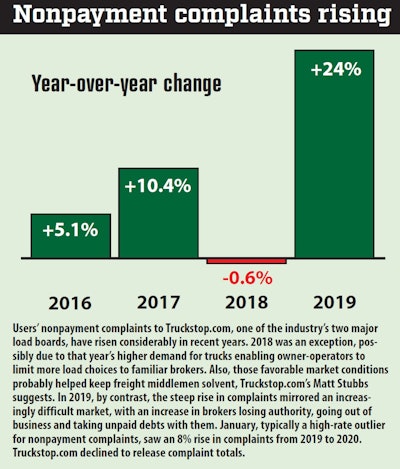

FMCSA data on brokerages filing for new or reinstated authority since 2015.FMCSA, however, has taken a step in the direction of identifying problem brokers. The agency in recent years added automated flags to regulated entities’ public profiles on its Licensing & Insurance website that can at least provide watchful carriers notice that a bond or trust is pending cancellation. Yet those flags alone don’t deliver the kind of confidence an authority suspension would, points out Willie Taylor, director of assurance data management for Truckstop.com.

The red listing shows that the surety is pending cancellation, Taylor says, but “it doesn’t tell me why.” Truckers are left to rely on their intuition about who they’re dealing with. Or they can take time to call the surety provider directly to find out whether the pending cancellation is a routine end of term or the result of a run-up in claims — not always a practical step, given the number of potential loads some operators consider every week.

FMCSA’s relatively new Unified Registration System for new authorities of all types has made it tougher, too, for problem actors to reincarnate and hide their past actions, says DAT Compliance Manager Tami Hart. It’s not been uncommon, she says, to see dishonest brokers “try and create multiple MC numbers. FMCSA is making it a little more difficult to do that, given the fact that they now have to disclose any relationships and affiliations.”

If they don’t do that disclosure and file with a new authority, the agency can crack down on the new filing. If, that is, the officials are not asleep at the switch and actually make that discovery.

There’s some evidence that it might be too easy to miss crooks’ use of multiple motor carrier numbers. Cedar Freight, LLC, successfully applied for brokerage authority in July. A list of carrier authorities revoked in Iowa shows two separate companies at the same mailing address used by Cedar Freight, both revoked earlier in 2019 for failure to respond to FMCSA’s New Entrant audit notice. (Follow this link for one carrier’s experience with short-lived Cedar Freight.)

There’s no sign that this and other possibly fraudulent behavior by brokers will be addressed anytime soon by FMCSA rulemaking. The agency is reluctant to get further involved with broker fraud, considering it to be a financial matter unrelated to safety, says a DOT source, speaking off the record. The source suggested that the relatively new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau or the Federal Trade Commission might be more appropriate for such oversight.

The Transportation Intermediaries Association, which represents larger brokers, disagreed about the link to safety in comments submitted for the 2018 ANPRM.

“Small carriers and owner-operators often operate on thin financial margins and need the revenue from every load to maintain their equipment so that it meets roadworthiness and safety requirements,” wrote TIA. “If they are not paid, necessary maintenance and repairs may be put off or ignored because of the reduced cash flow.”

OOIDA echoed the argument in its comments: “When many motor carriers are living load by load to support their families and maintain their vehicles, loss of one payment of $2,000 or more can cause them to defer maintenance and run harder until they make up the shortfall. These issues are distinctly related to safety.”

The DOT source says further action on the proposed rule lies with the White House Office of Management and Budget, where it now languishes. “USDOT/FMCSA is part of the Executive Branch of government, so it’s entirely up to OMB,” he says.

An OMB source, speaking off the record, says “this rule is not with OMB. I’d refer you to DOT.” The OMB status page for the rule lists its “legal deadline” as “none” and its status as “next action undetermined.”

Next in this series: A ‘hit it and move on’ broker scam — and more loopholes