Previously in this series: ‘You just lose’ when middlemen don’t pay: Broker reform eight years in the waiting

That phrase – “hit it and move on” – was DAT Compliance Manager Tami Hart’s description of what amounts to a crooked business model among a small fraction of federally authorized brokers: Move as many loads as possible, fail to pay carriers and vanish. A big part of that is exploiting the time lags in current notification requirements of surety providers and the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Association to run up as much business as you can before your authority is revoked over valid claims from unpaid owner-operators and fleets.

Idaho-based Allan Workman speculates that such a case last year was plenty lucrative indeed for the brokerage, Cedar Freight. It was in business about four months.

Workman received no more than a prorated 35% on a claim made to a surety provider on what may have been the first load moved by the federally authorized broker out of Iowa. Assuming all claimants were paid at 35%, he says, the bond maximum of $75,000 covered some $215,000 in business conducted by the broker. Since some cheated clients never file against the bond, the real theft total could well exceed that.

“To get a bond, it’ll cost you $3,500 to $7,000,” Workman estimates, and a couple more thousand for corporate registration in the broker’s state and the authority application. “So you might put out $10,000 to make $200,000 and more” in a few months, and take the rest of the year off. “Throw your ID away and start over again.”

To make matters worse, the assumed $215,000 in claims approved for prorating by the bonding company doesn’t include any loads subject to little-known exemptions to surety requirements: certain commodities and, in this case, intrastate loads.

![Allan and Billie Workman, based in Idaho, specialize in overdimensional loads. Last year they hauled two intrastate loads for a broker who failed to pay them and disappeared. In Allan’s 37 years trucking, he’d heard horror stories about nonpayment but had escaped such problems. Now, he said, “instead of just looking at a load [online] and booking it,” few questions asked, “it takes me a half-hour or more to investigate it.”](https://img.overdriveonline.com/files/base/randallreilly/all/image/2019/11/ovd.Allan-and-Billie-Workman-2019-11-05-14-19.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&q=70&w=400) Allan and Billie Workman, based in Idaho, specialize in overdimensional loads. Last year they hauled two intrastate loads for a broker who failed to pay them and disappeared. In Allan’s 37 years trucking, he’d heard horror stories about nonpayment but had escaped such problems. Now, he said, “instead of just looking at a load [online] and booking it,” few questions asked, “it takes me a half-hour or more to investigate it.”

Allan and Billie Workman, based in Idaho, specialize in overdimensional loads. Last year they hauled two intrastate loads for a broker who failed to pay them and disappeared. In Allan’s 37 years trucking, he’d heard horror stories about nonpayment but had escaped such problems. Now, he said, “instead of just looking at a load [online] and booking it,” few questions asked, “it takes me a half-hour or more to investigate it.”

Dean Jutilla of uShip says that the shipper in this case took a risk by doing something that uShip doesn’t recommend: contracting with an entity that then had no review on the platform, not to mention little to no history in business as a broker. However, “Everybody’s got to start somewhere,” he says of Cedar Freight’s broker account.

Workman then found the load posted by the broker on a different online platform, Truckstop.com, where a $2,000 offer rate, more than the shipper ultimately paid the broker, was an attractive carrot for hauling only 64 loaded miles. Workman didn’t look up Cedar Freight’s authority history before accepting the load. Had he done that, he would have seen that authority had become active mere days earlier.

Owner-operator Workman hauls in this 1999 Kenworth W900L powered by a relatively rare 16-liter Cat factory 600 motor, he says.

Owner-operator Workman hauls in this 1999 Kenworth W900L powered by a relatively rare 16-liter Cat factory 600 motor, he says.He hauled another such load within Washington for the broker shortly thereafter for a promise of $2,700, involving pilot cars, special permitting and more. These loads moved in July and August, respectively.

After failed communications with Cedar Freight about getting paid, including promises of checks in the mail, he filed on the company’s surety bond in early October. Only then did he learn from the bond provider that, since these were intrastate loads, they weren’t covered by the bond. It’s a huge loophole Workman and others feel owner-operators would do well to keep in mind before accepting intrastate work from an unfamiliar broker.

Likewise, an unscrupulous broker can exploit shipments of exempt commodities – such as fresh produce, forest products and more – that aren’t covered by brokers’ bonds. (Search “Administrative Rule 119” at fmcsa.dot.gov for a full list of commodities and their exemption status.)

“It’s a legal way to steal,” Workman says. “What’s the remedy unless you sue them in court?”

Had the owner-operator been able to establish any confidence in the identity of the person behind the brokerage entity, he says he wouldn’t have hesitated to file a court action in the broker’s jurisdiction. Filing suit is a cumbersome, uncertain remedy for nonpayment.

Workman later remembered that the first intrastate Washington load he moved had in fact crossed from Eastern Washington briefly into Idaho while in transit. That made it interstate and covered by the bond. Word about Cedar Freight had traveled fast among owner-operators by then, and claims flooded in. Workman finally received around $800 for that $2,000 load, meaning he’s still out $3,900 for his dealings with Cedar Freight.

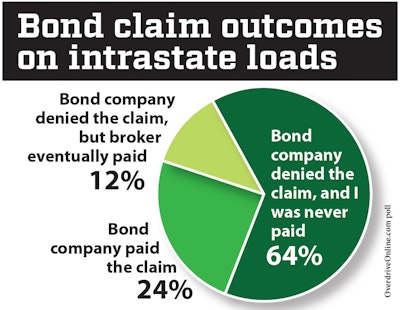

Brokered intrastate loads, moving from pickup to destination within a single state, are exempt from federal regulations addressing brokers’ required surety. Few carriers know about the intrastate exception. A more common surety exemption is for certain brokered commodities such as fresh produce. However, the poll shows that in some cases, bond claims for intrastate loads have proven successful in getting compensation from the bonding company or giving the broker the extra nudge to pay.

Brokered intrastate loads, moving from pickup to destination within a single state, are exempt from federal regulations addressing brokers’ required surety. Few carriers know about the intrastate exception. A more common surety exemption is for certain brokered commodities such as fresh produce. However, the poll shows that in some cases, bond claims for intrastate loads have proven successful in getting compensation from the bonding company or giving the broker the extra nudge to pay.The bonding company notified FMCSA of a pending cancellation in late October, and Cedar Freight’s authority was revoked just after the cancel date on Nov. 27. After receiving complaints, the uShip.com platform canceled Cedar’s account around the same time, as had Truckstop.com, Workman says.

“How do you get something like this resolved or put the brakes on it if it’s happening quite often?” he asks. “It’s a shame, and I think the public needs to know about it.”

Next in this series: Critics say trust fund surety fails to protect truckers in claims against brokers