Previously in this series: Growing broker/carrier identity theft schemes reaping millions

This report is newly updated as of November 18, 2020, to include this video in which U.S. Postal Inspector Steve Cohen offers firsthand detail on what he found in investigation of this double-brokered freight fraud scheme:

Postal Inspection Service inspector Stephen Cohen notes it’s virtually impossible to stop someone from using your name once your identifying information is compromised. Nevertheless, a few extra steps taken early can immediately derail some schemes involving business impersonation, particularly the fuel-advance ID theft scam detailed in the prior part in this series and in the video discussion with Cohen above. (Catch our full discussion with Cohen via this edition of the Overdrive Radio podcast, too.)

Broker due diligence

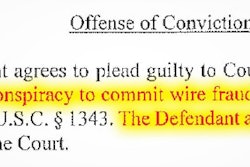

No. 1: Verify insurance independently | The identity thieves in the scam tied to William Francis Hickey III, Cohen said, were very good at preparing insurance documentation that looks like the real thing, but with phone numbers or email addresses changed. When a broker gets an initial contact from a carrier, and the carrier provides its insurance company information, don’t just contact the email or phone on the certificate provided, as it could be fraudulent. Use DOT’s official system via Safer.FMCSA.DOT.gov, and the internet in general, to better identify through public sources the veracity of what the carrier has sent you. Call the number you find online at an official website, not the number provided by the carrier bidding on the load. “If brokers do this, 95 percent of the time, the attempted scam is over,” Cohen says.

After a suspected case of fraud employing theft of her business identity, owner-operator Debbie Desiderato put a note on her business’ DAT profile to mitigate against a broker falling for such a scam: This company does not request fuel advances. “Brokers should reconsider issuing fuel advances,” she said, echoing U.S. Postal Inspector Cohen. “It needs to start with the broker.” Desiderato also notified her insurance company to ping her anytime a broker requested verification of her insurance information, for her own peace of mind.

After a suspected case of fraud employing theft of her business identity, owner-operator Debbie Desiderato put a note on her business’ DAT profile to mitigate against a broker falling for such a scam: This company does not request fuel advances. “Brokers should reconsider issuing fuel advances,” she said, echoing U.S. Postal Inspector Cohen. “It needs to start with the broker.” Desiderato also notified her insurance company to ping her anytime a broker requested verification of her insurance information, for her own peace of mind.No. 2: Don’t offer a fuel advance to a first-time trucking company | Brokers successfully targeted by a crook’s stolen carrier identity are likely to be none the wiser if the scheme works. Cohen said that if it happens to them once, they could be likely to get hit again, and sometimes quite quickly. Cohen recommended brokers put a policy in place against allowing fuel advances for first-time carriers. These crooks “aren’t going to provide bank accounts to brokers,” Cohen said, as they need to “keep their runners from being identified,” hence the targeting of fuel advances and check express codes. “When they don’t get the fuel advance, they don’t keep going.”

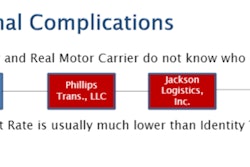

Chad Boblett’s Rate Per Mile Masters Facebook group can be a place to discuss with both owner-operators and brokers the evolving scams that exist. A broker member, Boblett said, pointed to what he said amounted to a double-brokering scam coming from carriers with sizable pools of independent freight agents and subagents working under their authority as well as trucks either owned or leased. The broker books a shipper’s load with one of the agents, thinking that load is then going on one of the carrier’s trucks, only to find out the carrier’s brokerage arm has rebrokered it out to an independent carrier, ultimately just putting another hand in the cookie jar of the overall freight rate. This kind of unethical fleecing of the rate has gone on for years, yet the difference in recent times, Boblett believed, is that it’s not exactly “the wild wild West out there anymore.” Do such a thing and you’re found out, and people will hear about it. His group has played a big part in that: “Brokers and carriers both can’t so easily get away with unethical practices.”

Chad Boblett’s Rate Per Mile Masters Facebook group can be a place to discuss with both owner-operators and brokers the evolving scams that exist. A broker member, Boblett said, pointed to what he said amounted to a double-brokering scam coming from carriers with sizable pools of independent freight agents and subagents working under their authority as well as trucks either owned or leased. The broker books a shipper’s load with one of the agents, thinking that load is then going on one of the carrier’s trucks, only to find out the carrier’s brokerage arm has rebrokered it out to an independent carrier, ultimately just putting another hand in the cookie jar of the overall freight rate. This kind of unethical fleecing of the rate has gone on for years, yet the difference in recent times, Boblett believed, is that it’s not exactly “the wild wild West out there anymore.” Do such a thing and you’re found out, and people will hear about it. His group has played a big part in that: “Brokers and carriers both can’t so easily get away with unethical practices.”Carrier due diligence

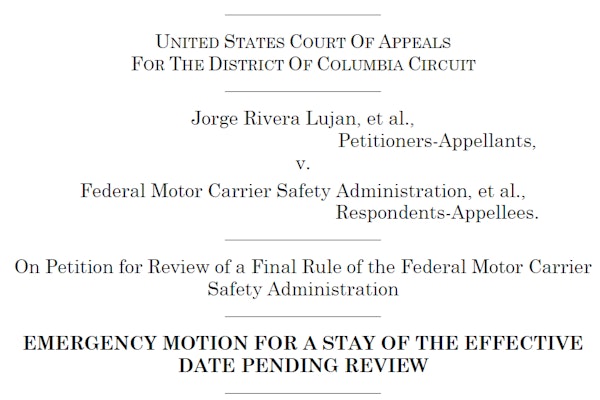

No. 1: Verify any broker’s identity independently | Owner-operator Chad Boblett of the Rate Per Mile Masters Facebook group recommends what he calls “two-call authentication” for any broker you’ve never done business with. Look up the broker on Safer.FMCSA.DOT.gov and use the listed contact number to verify the identity of the person you’ve been dealing with. “I see a lot of people skipping that, especially if they’re already set up with that broker,” Boblett said. “Just call and say, ‘Hey, I got the load from this particular person. Are we set up? Is this all good? This is where I send the invoice where I’m done?’ I’ve never had a broker not like that when I do it. They totally understand and they also say I’m one of the few that does it.” With email communications, be very skeptical of a broker communicating with you through a gmail or other free-email-service address, too, as opposed to a company domain name. Use public sources of contact information to verify.

No. 2: Get confirmation of the broker’s identity from the shipper | Use your access to the shipper to verify “who the broker on the load really is,” Cohen said. If the names don’t match up with who you’ve been dealing with, you may have been had. Cohen said thieves in his case tried to mitigate the possibility of being found out this way by claiming the load was a “blind shipment,” or “blind load.” That’s common enough terminology for a situation where the identity of the receiver isn’t known to the shipper, and vice versa in some cases, often when a distributor is trying to protect its business from either party. If you hear the phrase from a broker, do the extra work to verify the legitimacy of the voice you’re dealing with.

Next in this series: How to vet brokers’ credit before taking a load