Previously in the “Broker reforms” series: Critics say trust fund surety fails to protect truckers in claims against brokers

In December, Walkabout Transport owner-operator Debbie Desiderato got a call from Grizz Logistics. The broker said Desiderato’s driver couldn’t run the load he’d negotiated because she didn’t have reefer breakdown insurance.

With that news, she realized there was a much bigger problem. “I don’t have a driver,” she told the broker, “and I don’t have a reefer.”

For weeks thereafter, Desiderato was convinced someone had used her DOT number in offering to move Grizz’s load. The broker had been convinced briefly, too, after having examined Desiderato’s insurance certificate in the course of conducting due diligence on the carrier.

When the broker noted the discrepancy in insurance coverage listed, Desiderato says, “the broker had the common sense to call the number associated with my DOT number.” The broker also gave her the name and number of the driver who’d been negotiating the load.

When Overdrive called that number, Four Hearts Transportation owner-operator Tomaz Sterczewski of Ocala, Fla., answered. It turned out if you remove the zero starting Sterczewski’s MC number, guess whose DOT number you get?

The fear of the broker and Desiderato – that a crook was attempting to exploit Desiderato’s stolen business identity – was a case of mistaken identity that caused no loss. But their alarm was fully merited, given the growth in business identity theft in the brokered-freight world.

This multipart series explores issues related to the financial security of freight brokers and fraud in freight transactions. Catch previous pieces of the “Broker reform” series via this link and stay tuned for more on how to prevent/combat the scammers.

This multipart series explores issues related to the financial security of freight brokers and fraud in freight transactions. Catch previous pieces of the “Broker reform” series via this link and stay tuned for more on how to prevent/combat the scammers.“We’ve seen a dramatic increase in identity theft,” says Willie Taylor, director of assurance data management for Truckstop.com. When Taylor started in his current position about three years ago, “I’d see maybe one a month in terms of cases” reported by board users. “We’re seeing two to three a week now, and we’re working them as fast as we can.”

Crooks can impersonate carriers or brokers. For Taylor, it’s the latter that “scares me most,” he says. “If someone can successfully impersonate a broker, he might quickly cause about $60,000 to $80,000 worth of damage in two, three days.”

In a recent case led by Postal Inspection Service Inspector Stephen Cohen, perpetrators impersonated both in an orchestrated fashion to get loads moved and pocket the payments. William Francis Hickey III, then a resident of Elkton, Md., is currently locked up for his role in the scheme.

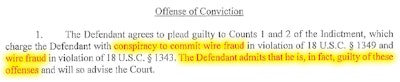

Hickey’s plea agreement shows him pleading guilty to wire fraud and conspiracy to commit wire fraud with others. As noted by Postal Inspection Service Inspector Cohen, Hickey’s unnamed coconspirators were outside U.S. law enforcement jurisdiction, as far afield as Pakistan. Hickey’s role in the fuel-advance and double-brokering identify theft scheme detailed below was key to laundering more than a million dollars to deliver a considerable amount of it to actors overseas.

Hickey’s plea agreement shows him pleading guilty to wire fraud and conspiracy to commit wire fraud with others. As noted by Postal Inspection Service Inspector Cohen, Hickey’s unnamed coconspirators were outside U.S. law enforcement jurisdiction, as far afield as Pakistan. Hickey’s role in the fuel-advance and double-brokering identify theft scheme detailed below was key to laundering more than a million dollars to deliver a considerable amount of it to actors overseas.The investigation began with the U.S. Department of Transportation Office of Inspector General, says Cohen. It eventually made its way to the Postal Inspection Service from the U.S. attorney’s office.

Hickey was “helping facilitate the moving of over a million dollars” overseas, where crooks in Pakistan “specialize in identity theft on a large scale,” Cohen says. “We have limited reach to identify who they are, so we focused on folks here.”

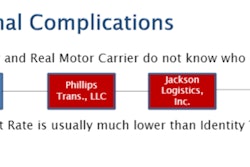

The scheme largely centered on the crooks’ ability to impersonate carriers, using trial accounts or other means to get into a load board. They’ll find “a legit load posted by a real broker,” perhaps moving chickens from New Jersey to Florida, Cohen says. “Then, using my stolen carrier information,” readily accessible via DOT websites and other sources, “I contact Broker A and tell them I can move the load to Florida.”

If Broker A accepts it, the thieves posing as a trucking company then use other stolen broker identity information to go back as “Broker B” to their load board of choice to double-broker the chickens. “They can either post that same load of chickens,” Cohen says, or, easier and more commonly, find a one- or two-truck owner-operator who’s posted as available.

They send that carrier to the shipper, instructing the carrier to email a copy of the bill of lading “as soon as you pick up the bill.” The thieves then “modify that to make it seem like they picked it up, and they send it back” to Broker A.

Next comes the play for a fuel advance – an old scam, though clearly still in use. In the case of Hickey and his co-conspirators, plenty often it worked, and the double-brokering scheme continued. After the duped carrier gets loaded and moves toward the destination, crooks get an express code from Broker A for a fuel advance check that can be cashed, then send it to Hickey, who launders the money.

That carrier hauling the chickens, still unaware, gets the shipper’s paperwork, emails it to fake Broker B, delivers the load, gets proof of delivery and invoices Broker B, who never pays him. But the crooks take the proof of delivery, go back to Broker A and get another express code for the full delivery amount and deposit it via Hickey.

“Hickey was receiving eight, nine, 10 checks a day,” Cohen says. “On any given day our suspects may be obtaining five to 10 different loads,” clear evidence well more than just one other person was involved here.

In some cases, though, losses to the carrier and/or shipper could “skyrocket” if Cohen’s “suspects couldn’t find a carrier to move the load” where they wanted it to go, he says. “They’d change the destination to a different place” in their posting to the load board or calls to the carrier. “Instead of the loss being just the amount of money the carrier didn’t get, [the shipper] might lose their load as well” if the crooks could convince the duped carrier to continue on a course to a false receiver address. In the case of fresh produce or other perishable load, the carrier could be stuck trying to salvage what was left if more favorable terms couldn’t be worked out with the original broker or shipper.

Yes, as Cohen noted about all these schemes, carriers tricked into involvement might ultimately find their way back to the original broker, via the shipper or other source, and get paid, Cohen says. Too often, though, that doesn’t happen.

Next in this series: How brokers, carriers can prevent business ID theft schemes