Previously in this series: Will enforcement use ELD data for purposes beyond hours of service?

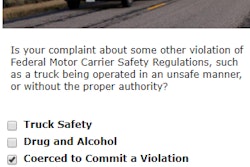

What will happen in situations where your electronic logging device documents an unavoidable violation? This could be driving beyond limits while looking for a parking spot in a congested area or moving from a parking place during an off-duty period when forced to by local law enforcement.

State and federal law enforcement officials urge drivers to practice blunt honesty, using annotations on duty statuses and status changes to explain the situation in detail. In many cases, officer leniency is likely to prevail.

Before e-logs, “getting the load there on time was the first priority,” said driver Bob Stanton, part of a panel convened by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration during the Great American Trucking Show in August. Before, “you made your log look legal” only after that first priority was met, he said. Now, if there’s any chance you can’t get deliver within legal hours, you need to make the appropriate calculations well beforehand.

Driver Bob Stanton (second from right) responds to an audience member’s question at the GATS ELD driver panel convened by FMCSA.

Driver Bob Stanton (second from right) responds to an audience member’s question at the GATS ELD driver panel convened by FMCSA.That seemingly simple change, however, is one that brings with it a raft of complications, from new administrative and operational burdens placed on drivers and carrier dispatch to the pressing need for shipper/receiver customers’ appreciation of the new dynamics.

Others at the GATS panel presented cases, including delays at shippers and receivers that exhaust on-duty hours. FMCSA enforcement specialist LaTonya Mimms noted officers will retain the discretion on whether to write a violation.

If the overage is “no more than 15 minutes,” Mimms said, the “trooper may or may not cite a nominal hours violation,” with little consequence for safety scores. In excess of 15 minutes, however, a normal violation would be the typical response from the agency’s perspective.

Two-truck independent Rico Muhammad has encountered such a situation, parked overnight outside a receiver’s closed facility, staged to unload in the morning. Run off by local law enforcement during his off-duty period, he used personal conveyance mode in his e-log (which continues the off-duty status when selected) to move five miles up the road to a spot. Loaded, however, that use of personal conveyance would open him up to a false log violation down the road if discovered, notes Joe DeLorenzo, director of FMCSA’s Office of Enforcement and Compliance.

DeLorenzo hears about special cases all the time, many having to do with just where personal conveyance is warranted or not. He emphasizes that it’s properly understood as truly personal use of the vehicle. Traveling to and from shipping/receiving locations isn’t the place to use it, though compliance consultants have argued otherwise, particularly for self-dispatched or independent owner-operators such as Muhammad (if empty).

When an exceedingly lengthy delay at the shipper or receiver causes the driver’s 14-hour clock to run out, DeLorenzo says proceeding to a safe haven/parking location/truck stop would not be considered personal conveyance. Rather, he urges drivers to make the trip and annotate the circumstances “in case somebody asks for it,” thus avoiding charges of a “false log” for incorrect personal conveyance use.

In mid-late November, DeLorenzo said the FMCSA would further clarify personal conveyance in light of the ELD mandate in a Federal Register notice, unavailable at press time.

DeLorenzo also clarifies the other special short-term driving category specified in the ELD rule: yard move. Using this category will move a driver to the on-duty not-driving status, even though the vehicle is in motion. Just where it can be used hasn’t been fully understood to date throughout the industry.

DeLorenzo says fleet terminals aren’t the only places where it’s OK to use; it’s also good within facilities away from public roads such as ports, railyards, customer locations and the like. At distances of no more than three to five miles, DeLorenzo says, “it’s OK. If it starts to accumulate more than that, people are going to start asking questions.”

Yard moves, after being categorized by the driver or registered automatically in a geofenced area, must be approved by the administrator. In the case of an independent, that makes use of the yard move a two-step process for the owner.

Self-incrimination by ELD will rise to the level of a violation only if someone decides that it does. Picky violations in special circumstances, says Capt. Brian Preston of the Arizona Department of Public Safety, are not going to get many in much trouble if they’re logged honestly.

What his officers are looking for, he says, is more the intent to deceive. At roadside, that most often manifests as someone having unplugged the ELD so that it shows they “went to sleep in Oklahoma and woke up in Texas.” Preston adds that “most humans just don’t lie very well” and inspectors are well-trained in dealing with drivers. If “right off the bat the situation doesn’t look right, if it looks like a game is being played, that will be the biggest deciding element” of just how in-depth officers go into a driver’s log.

Lt. Dan Wyrick of Wyoming says he’s seen scenarios where drivers don’t log in for a certain time to mask movement. He’s also seen “the company cheating the system by reassigning driving time” on the back end, which will be impossible to do without driver involvement under the new ELD specification. With ELDs, unlike AOBRDs, drivers must approve any office edits.

Veteran officers believe electronic and paper logs have similar enforcement dynamics, Preston adds. What’s different with paper are the form-and-manner formatting errors that get recorded – ELDs virtually eliminate those. Generally, enforcement philosophy will not change.