Previously in this series: More hopes and hazards: ELD data aggregation for advocacy, predictive maintenance, other uses

Safe Way Carrier began working with broker One Point Logistics about a year ago, says the fleet’s technology/billing manager, Jon Gavrilyuk. A short time after that, he began to notice “a lot more focused freight from different areas around the country,” he adds.

He thought it might be a benefit of the fleet’s growing relationship with OPL. What Gavrilyuk didn’t know was that KeepTruckin, Safe Way’s ELD provider, had acquired OPL at a time that roughly coincided with the uptick in that “more focused freight.”

Letting its acquired brokerage glean insights from customers’ aggregated, anonymized ELD data effectively put KT in a position of competition with its own ELD users, who generated the data, or their brokers. KT CEO Shoaib Makani defends the company’s internal use of anonymized data as critical ultimately in its efforts to help customers in fighting detention or getting optimized load offerings.

Situations such as this show how the possession and use of massive amounts of data can change traditional balances of power in spot market rates and negotiations.

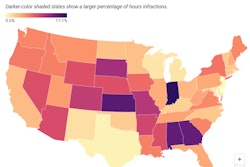

FreightWaves’ Daniel Pickett acknowledges the potential for carriers’ information to be used against them in rate negotiations, should brokers or shippers be able to establish the carriers’ operational patterns.

For instance, he says, assume an owner-operator wanting to return home to Dallas for the weekend is trying to negotiate a Thursday pickup for a load from Chicago to Dallas. Brokers “could bargain harder with you because they know you won’t have to deadhead if you wind up near Dallas.”

He hasn’t seen that occur, he says, “but that certainly is the risk if you’re using apps that can track you, whether it’s an ELD or a brokerage app. You do need to think about the patterns they can build on your data.”

Brokers also have expressed concern about ELD data being used to tilt the market against them.

Jeff Tucker, CEO of Tucker Company Worldwide, admits the sudden widespread nature of ELD data “scares the daylights out of me.” He sees distribution of ELD data as skewing the market unfairly.

Tucker’s concerned with “the explosion of IT and tech startups who are taking that data and creating their own little marketplaces with it.” Such companies are “taking part of my data and part of the carrier’s data – which is really private between me and my carrier – and they’re putting it out to the market and putting a value on it and making money off of that data. That’s without my permission and without the carrier’s permission.”

KeepTruckin’s user agreements, like those of many ELD providers, ask customers for their permission to share anonymized ELD data or use it internally to develop new products. Customer permissions, though, had no bearing on the acquisition of OPL, which wasn’t announced during the first six months of ownership. Gavrilyuk learned of it only after KeepTruckin announced it in April.

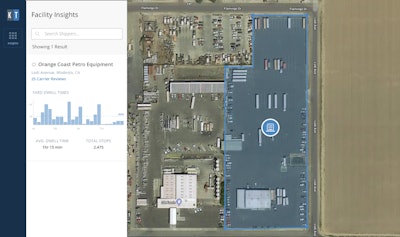

Also at that time, KT announced its coming Facility Insights tool, which uses ELD data to help its customers gain critical information about detention times. The company also touted its work on a freight marketplace it’s calling the Smart Load Board.

At that point, KeepTruckin had owned and begun to expand the brokerage for about six months. The company relied on a variety of resources, including its facilities detention measurement tool built with carrier data, to grow OPL.

KeepTruckin’s Facility Insights tool will feature average dwell times for thousands of shipper/receiver load locations, gleaned from ELD users’ data. The ability for users to review such facilities is set to follow.

KeepTruckin’s Facility Insights tool will feature average dwell times for thousands of shipper/receiver load locations, gleaned from ELD users’ data. The ability for users to review such facilities is set to follow.A KeepTruckin ELD user, Hallahan Transport owner-operator Rob Hallahan, based in La Crosse, Wisconsin, said KT’s use of carrier data for six months before announcing the broker acquisition “sounds like a form of insider trading.”

To ease such concerns, Makani says the company might create a data-share wall between OPL and the central KT team upon this year’s release of the company’s load board.

“We do want this to be an open platform,” he adds of the load board, without preferential access for the OPL brokerage.

Makani sees the brokerage, the detention tool and the load board, as well as the data shared among them, as interrelated in giving KT’s customers leading-edge tools.

He acknowledges it’s an open question as to whether brokers will be willing to participate in a service whose developer also happens to be a competitor of theirs. But when KT’s load board is launched, he says, OPL will operate just as any other participating broker, with access to the same data those brokers have, he says.

“We couldn’t have built this load board and made it a great experience unless we were moving freight,” Makani says, which necessitated the purchase of OPL.

While aggregated ELD data can benefit industrywide improvement efforts and regulatory developments, putting trucking trip data in the hands of governments, as the Geotab company has done toward assisting in road improvements, also could carry some downsides, including an impact on competition.

A recent Wired story showed how the city of Los Angeles built a system under which scooter- and bike-share providers are required to share trip data with the city. The city’s plans were to anonymize the data for any public consumption, and to prohibit sharing the data with law enforcement unless required by subpoena. Other cities adopted similar rules, aiming to control congestion of such vehicles.

Some large cities’ interest in trip data from shared vehicles, such as scooters and bicycles, shows how governmental entities could begin to mine ELD data that records truck trips. Some observers worry that exposure of certain data could compromise carriers’ competitive positions.

Some large cities’ interest in trip data from shared vehicles, such as scooters and bicycles, shows how governmental entities could begin to mine ELD data that records truck trips. Some observers worry that exposure of certain data could compromise carriers’ competitive positions.Consumer privacy watchdogs and ride-share companies such as Uber and Lyft are fighting the L.A. rules. Their worries: the privacy implications of relying on governments to anonymize data, a slippery slope of regulation, and exposure of intellectual property underlying their operations.

Truckers also have been concerned over the intersection of data privacy with competition. ELD providers “can already follow you into your customers” by reidentifying data around facilities, wrote Overdrive reader Jeff Pearson, commenting on Part 1 of this series. “What’s next, the cops can sit at their office writing you speeding tickets?”

Geotab executives say they are aware of the sensitivity of data when it comes to market competition.

In a 2017 Overdrive interview with Dirk Schlimm, Geotab executive vice president, he emphasized that competitive issues could be of greater importance than individual privacy issues when it comes to business data. In Geotab’s internal deliberations over what tools to develop and with whom to share them, it’s a key consideration.

“We’re asking that question first,” Schlimm says. “ ‘Is this a benefit to our customers?’ ”

A backlash over the use of private data by service providers has been brewing since long before the ELD mandate, says Kenny Lund, vice president for ALC Logistics. His company also produces a transportation management system for shippers, whose data it keeps walled off from its principal business of truckload brokerage.

Information technology companies are “blatantly pushing” to get truck data and profit from it, he says. “My prediction is that truckers will ultimately say, ‘No, I’m not giving you that information.’ But also, shippers and brokers will realize that tracking tractors and drivers is ultimately problematic for them, too.”

Some of the third-party logistics providers and tracking-technology providers used by Maverick Transportation’s shipper customers are “asking for all our data, but we are not giving it to them,” said President John Culp, speaking at the Truckload Carriers Association annual meeting in March. “We still feel that for the relationship we have [with the customer], to provide service, we need to protect our data.”

Generally, however, there are no organized efforts pushing against the issue of liberalized ELD data use. Since the information technology industry has moved the boundaries on privacy, and given a soft stance from the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration on regulating ELD data, such efforts may be hard to muster. —Aaron Huff contributed to this report.

Find the first installment from early this month in this broad series on ELD data handling via: