Bad driving habits — such as running regularly too fast, above your engine’s fuel-efficiency sweet spot — are among the primary reasons for increased fuel consumption and reduced profit.

Bad driving habits — such as running regularly too fast, above your engine’s fuel-efficiency sweet spot — are among the primary reasons for increased fuel consumption and reduced profit.Your survival depends on minimizing fuel consumption and getting a fair surcharge

Much attention is given to cost control when, in reality, “waste control” is what owner-operators should be watching. This is especially true for fuel, an owner-operator’s number one cost. You can make the wisest business decisions about fuel when you know your fuel economy, expressed in miles per gallon, and your fuel cost per mile (CPM).

Calculate your mpg simply by tracking your mileage between fillups and dividing the total by the number of gallons you burned; do this for all trips. Fuel economy constantly changes, affected by weather, loads, routes, traffic, terrain, road surfaces and other factors. Many may be out of your control, but no problem can be remedied if it isn’t noticed.

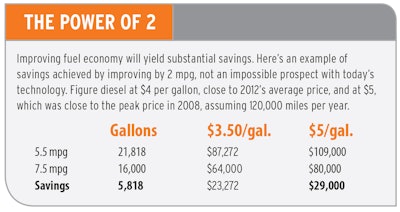

It’s helpful to know mpg per month, per week and even per load. That occasional haul of steel across the Appalachians may be costing you more in fuel than it’s worth. If your numbers look bad, don’t give up; the worse your fuel economy, the more you have to gain by improving it.

Armed with your mpg, calculating your CPM is easy. Suppose your truck gets 6 mpg, and you ran 6,000 miles in a month, meaning you burned 1,000 gallons (6,000 divided by 6). If diesel averaged $4 per gallon that month, your total cost was 1,000 x $4, or $4,000. Your fuel CPM was $4,000 divided by 6,000, or 67 cents – likely the largest single chunk of your total CPM. It will pay you huge dividends to consider strategies for cutting your fuel bill.

For good fuel economy, your truck has to overcome three things: rolling resistance, air resistance and gravity. Fortunately, your driving technique and other choices you make can address each of these. Let’s look first at two of the biggest areas for cutting fuel costs.

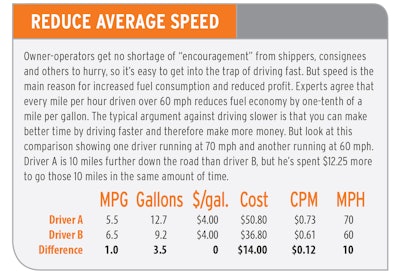

That might not seem like much money, but look at the impact during an entire year. If you drive 130,000 miles per year and average 5.5 mpg vs. 6.5 mpg because you drive faster, you will spend $12,727 more on fuel. In essence, you gave yourself a 10-cent-per-mile pay cut.

Most owner-operators net about 40 cents per mile. If you divide the extra $12,727 fuel expense that driving faster costs by your net per mile of 40 cents, you would have to drive 31,818 miles more per year just to pay for the extra fuel. When you look at it this way, speed actually costs you time. Throughout the year, the hours-of-service limits will mean that on some days you’ll log fewer miles at 55 mph than you would at 65 mph. Even so, you won’t lose anything close to 31,818 miles.

LIMIT IDLE TIME

Idling requires about a gallon of fuel per hour, which can cost you about $160 per week at $4 per gallon if your truck idles eight hours a day. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, line-haul trucks not equipped with auxiliary power units might idle about 20 percent to 40 percent of the time the engine is running to power climate-control devices and sleeper compartment accessories and to prevent startup problems in cold weather.

Just because idling is common doesn’t make it smart. Idling on average costs $3,500 or more in fuel alone per year. This doesn’t include the added engine maintenance expense that results from excessive idling, which is harder on your truck’s engine than highway driving. In addition to operating costs, many governments impose no-idling laws with fines as high as $25,000.

Instead, there are many alternatives. An extra blanket for cold temperatures and window screens for when the weather is warm make it easier to turn off the engine. For about $80, you can buy a remote starter with a temperature sensor that will start the truck at a specified temperature. Infrastructure in truck stop parking lots to provide electrical power and auxiliary heat and air continued to increase in 2013, with many truck stop electrification (TSE) installations coming online for the first time.

Auxiliary power units (APUs) can pay for themselves in a reasonable amount of time. A mobile generator costing as little as $200 will burn less fuel and provide heating and cooling. Not idling is even a point of pride for many truckers who long have realized the benefits of shutting down the engine.

Choosing idle-reduction technology. This can be a difficult decision. Systems and costs vary widely. Several years ago, a study by the American Transportation Research Institute put diesel-fired heaters at the bottom of the cost range for purchase ($888) and annual maintenance ($110). Full-function diesel APUs/gensets are at the top, up to $8,000 or more.

If you go shopping for the cheapest system on the market, you may be disappointed with the features or overall quality. Buying an APU that doesn’t match your needs is a poor investment.

Search with two main goals – finding a system that fits your application and one that gives a healthy return on investment. No one has cornered the market with a one-size-fits-all system. When deciding whether to go all-electric, diesel-powered or hybrid, the decision comes down to practical power-supply needs and personal preference.

Evaluate your idle-reduction need by keeping a detailed idle log. Write down every time you idle and why. Keep track of hours idled and sort them by reason, such as air-conditioning, heat, AC power, warming the engine, etc. Try this for a year, accounting for all seasons. That may not be practical, but if you keep this log for three months and are disciplined in your records, you will be able to make good estimates for the other seasons.

If you skip this first step, you will drastically underestimate the amount of time you idle; you’ll also fail to understand the reasons you idle. Idling solutions have pros and cons and most revolve around the reason for idling; if you idle only because you need heat, then a full-blown APU is overkill. A better solution is a small diesel-fired heater, which is easy and inexpensive to use.

If you idle to produce AC power for a computer, TV, coffee maker, microwave, etc., you also can find inexpensive alternatives to a diesel-powered APU. One TV maker is releasing flatscreens that run well on 12-volt systems. Inverters and absorbed glass mat batteries will keep small appliances running for days. Add a small solar panel, and you can keep the batteries conditioned and extend that time as well, perhaps using some of the new TSE installations if you need to park for an extended period.

Once you have a clear understanding of how often you idle and why, research the options in today’s market. Then calculate the break-even point and return on investment for each solution. This methodical approach will reward you with an idle-reduction technology that fits your operation and budget.

Determining APU return on investment

How long it takes to recoup the money you shell out for an APU can vary considerably.

The more hours you can quit idling, the quicker the return on investment. With a full-function diesel-driven system costing $8,000 to $10,000, a good payback would be less than 24 months – or even 18 months if you are running hard and the price of fuel is high.

Any good APU dealer can help you figure your return on investment based on your idling habits, truck/sleeper size, normal freight lanes and accessory power needs. If the system you are considering is a diesel-powered unit, find out the per-hour operating cost.

If a system burns 0.2 gallons of diesel per hour and the average fuel used to idle is 1 gallon per hour, you have net fuel savings of 0.8 gallons per hour. Multiply that by the number of hours you idle (by day, month or year) times the price of diesel fuel to get your overall savings.

Weekly fuel savings

Hours idling: 50

Fuel price: $4

Cost to idle: $200

Cost to use diesel APU (0.2 gallon per hour): $40

Cost to use electric system: $0

Savings (diesel-powered): $160

Savings (battery-powered system): $200

Does not include maintenance cost, repairs or replacement parts

OTHER SMART PRACTICES

In addition to reducing speed and idling, there are several other good fuel conservation practices, each of which can reduce your fuel bill by 1 percent to 3 percent — or several hundred dollars a year:

Watch Cash Flow. Don’t tie up money needlessly in the fuel tank when downtime of a few days or more is expected. If you know a low-price area is on your route, don’t fill up at a more expensive stop; limit your purchase based on your mpg.

Buy the Right Fuel. If you’re in areas where farm vehicles are prevalent, it may be hard to find ultra-low-sulfur diesel. Check labeling if you buy from any outlet that’s not clearly a truck stop. With 2010 engine technology, low-sulfur diesel would interfere with proper operation of the diesel particulate filter and the selective catalytic reduction system, and could cause permanent damage.

Be Cautious with Biofuel. Biofuels tend to be expensive and produce lower fuel mileage. Know the level of biofuel (B20 is 20 percent biofuel) allowed under your engine maker’s warranty, and use only approved fuels. Carry extra fuel filters, as biofuel can cause clogging.

Maximize Storage. Whether you’re buying a used or a new truck, opt for larger dual tanks. This gives you the option of pigging out on super-cheap fuel and cutting down on the number of fuel stops, saving time.

Spec Your Truck Wisely. Your paycheck will show whether you chose a truck with a big engine and a lot of chrome or a truck engineered to meet your business needs and help you succeed. First, there is the initial extra expense for the purchase, then the added cost of fuel consumption. Weight and maintenance are in even sharper contrast between a lifestyle truck – a wannabe show truck – and an aerodynamic truck that is an efficient tool for business. In fuel savings alone, the aerodynamic truck generally more than offsets the resale value of the stylish truck. It also yields greater load capacity, more comfort, less noise and higher profit. On the other hand, operators with too-low horsepower settings for the application will find their feet always hard on the throttle, consuming more fuel. Some have benefited in fuel economy by retuning the engine control module for maximum fuel economy, installing full-flow mufflers or utilizing one of several new engine/transmission combinations built for maximum mileage, offering peak torque at much lower rpms than traditional diesels.

Consider Alternatives to Diesel. Interest in natural gas as a viable Class 8 fuel skyrocketed during the unprecedented 2007-08 fuel price spike. That brief affair ended as prices dropped when the subsequent recession hit, but today prices well above $3 per gallon have become something of a norm. Though natural gas fueling infrastructure is lagging, several new networks are in the works. Truck manufacturers have put big investments in natural gas technology and products. While natural gas trucks are expensive, they have a fast return on investment due to the decidedly lower cost of the fuel. A new natural gas truck can cost as much as $40,000 in incremental upcharges over a conventional and comparable Class 8 diesel truck, but cost-per-gallon equivalent has been as little as a third the cost of a gallon of diesel today. Despite power density and range limitations compared to diesel, natural gas appears to be working for those willing to accept those tradeoffs in return for lower fuel prices.

Think Aerodynamic. There’s plenty you can do to make your existing truck more aerodynamic. Snug the trailer tight to the tractor, which cuts down on wind resistance. The ride may not be as good, but the savings are worth the tradeoff. Add features such as roof fairings, chassis fairings, cab extenders and aerodynamic mirrors. Mount air cleaners under the hood. Use all-position tires on the rear, and make sure they’re the same tread as the steer tires. Match sleeper package to application; when you’re pulling tanks or flatbeds, a flat-top sleeper is the most aerodynamic option. And keep your gross vehicle weight as light as possible; even if you make up for those weight savings with heavy loads, you’ll greatly improve your fuel economy per pound of cargo. If you own a van or reefer trailer, investing in side skirts and trailer tails has resulted in 1-mpg gains or more for some operators. If you run wide-single tires instead of duals, cut down your mudflaps or invest in flaps that match the width of the tires.

Perform Regular Maintenance. This ensures your truck is running efficiently. Also, check your current miles per gallon at each fill – if it falls off, determine the reason. Start a preventive maintenance routine; check often enough to catch low oil, a dirty air filter or an air compressor leak. Don’t use a higher-viscosity oil than you need

Get any dangling bumpers or cockeyed mirrors fixed immediately, as they’re adding to your truck’s air resistance.

Maintain Tire Pressure. To reduce rolling resistance, check air pressure in all 18 tires and fill them up at least weekly to the manufacturer’s specifications. The trailer tires may belong to your carrier, but why pay the extra cost of pulling a trailer with underinflated tires?

Slow Your Acceleration and Deceleration. Both will consume less fuel and be easier on the mechanics of your equipment. Slowing acceleration is especially important running on hills or in the mountains because it helps reduce the effects of gravity. Rapid acceleration gets you an extra few seconds but creates premature wear on the engine, driveline and tires – along with increasing your fuel costs. Hard and frequent braking converts precious fuel to wasted energy; much of the fuel you need to get up to speed again is lost. Safety experts recommend watching ahead a distance of 12 seconds so you never have to react at the last second. You also won’t ever have to engage the engine retarder in city traffic if the “12-second rule” is followed.

Shift Wisely. Don’t drive by engine sound but by rpm. If you’re not absolutely sure about your engine’s sweet spot, ask the manufacturer.

Cut Out-of-Route Miles. If you’re like many owner-operators with 6 percent to 10 percent of your miles out of route – lost to detours, side trips and simple “Did I just pass my exit?” confusion – you possibly could cut them 3 percent. Doing so would save an extra 3 percent on fuel, as well as on other variable costs such as tires and maintenance. Rethinking your route, keeping side trips to a minimum and getting better directions will pay off in savings.

For more fuel-saving tips, visit OverdriveOnline.com/fuel-savings-tips to view our fuel savings microsite, offering 67 different tips on saving in five categories — Tires, Aerodynamics, Data Analysis, Driving Strategies and Anti-Idling — among other tips.

GETTING A FUEL SURCHARGE

As fuel prices have trended higher, fuel surcharges have become more widespread and – in many cases – more generous, as carriers have used them to help operators guard against price spikes.

How to Figure What a Surcharge is Worth. As long as you know your truck’s fuel economy, you can calculate how well a fuel surcharge compensates you for rising prices.

Many carriers pay a surcharge when the national average price for a gallon of diesel, as reported weekly by the U.S. Department of Energy, exceeds a certain price – often $1.10 to $1.25. The surcharge increases incrementally with diesel prices, either on a cents-per-mile basis or on a percentage of what the customer pays the carrier for the load. Carriers often structure their surcharge scale by assuming a certain fuel efficiency, such as 6 miles per gallon.

Some owner-operators make a healthy per-mile profit from their carriers’ surcharge because good fuel economy practices allow them to average better than 6 mpg. While surcharges traditionally have been based on the national average of diesel prices, in recent times – particularly in the case of dedicated regional routes – they are based on regional prices or prices along specific lanes. This can be a double-edged sword with customers; the same company that will pay extra for loads traveling only in Western states might ask for a discount on trips in other areas. For examples of surcharges along specific lanes, visit fuelsurchargeindex.org.

Surcharge Figured as Per Mile. Suppose a surcharge is designed to cover increases above $1.25, and fuel costs $4. Ideally, you’ll receive a surcharge covering that $2.75 spread.

If your truck gets 6 miles per gallon, divide $2.75 per gallon by 6 mpg. That equals 46 cents per mile. A surcharge at that level allows you to break even. Now assume you actually get 7 mpg. Dividing the $2.75 cents by 7 means a surcharge of only 39 cents per mile is needed to break even. If you’re driving for a fleet that has a surcharge based on its company trucks’ 6 mpg average, you come out 7 cents per mile ahead.

Surcharge Figured as Percentage. An owner-operator offered a surcharge that is a percentage of gross revenue does a similar calculation. Take the same situation – you get 6 miles to the gallon and diesel is $4 a gallon, so you need a surcharge of 46 cents per mile to cover your costs. Assume you’re offered a 1,000-mile haul for $1,100 in gross revenue. Start with your 46 cents per mile target for a surcharge and multiply by miles.

Now see what your $460 surcharge would be as a percentage of the gross. Divide it by $1,100 to get 42 percent. That’s the level you need to cover your extra fuel costs.

There are no rules covering fuel surcharges. As with freight rates, anything goes. But once you understand how surcharges work, it’s easy to see the potential for profit. Because fuel surcharge calculations involve some sort of fuel mileage average, a fuel-efficient owner-operator or small fleet owner always can beat the averages.

FINDING THE CHEAPEST FUEL

An effective fuel-buying practice is to maximize fuel purchases in low-fuel-tax states and mileage run in those states. The International Fuel Tax Agreement between the United States and Canada facilitates the reporting, collection and distribution of taxes to states and provinces. You pay taxes every time you fuel, but your ultimate fuel tax bill is calculated according to where you drive. If you purchase fuel in high-tax states and drive most of your miles in lower-tax states, you will get a refund when you file your IFTA report.

You cannot lower your tax outlay unless you choose hauls that avoid high-tax states. What you have more control over is how much you pay strictly for fuel when the fuel tax is not considered.

Pump Price — Taxes = Real Cost. The key to finding the cheapest fuel is to know the current fuel tax rates, both federal and state, and any state surcharges. Subtract taxes to find the raw fuel cost in each state, then buy where fuel is cheapest. The strategy means that you buy without regard for whether you are paying more at the pump — or in taxes at the end of the quarter.

Paying close attention to your routing will help you avoid rush-hour traffic delays that can put a dent in your fuel mileage.You cannot lower your tax outlay unless you choose hauls that avoid high-tax states. What you have more control over is how much you pay strictly for fuel when the fuel tax is not considered.

Paying close attention to your routing will help you avoid rush-hour traffic delays that can put a dent in your fuel mileage.You cannot lower your tax outlay unless you choose hauls that avoid high-tax states. What you have more control over is how much you pay strictly for fuel when the fuel tax is not considered.

IFTA also considers state surcharges, which complicate the fuel-buying strategy. Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, Vermont and Virginia have per-gallon surcharges; Idaho, New Mexico, Kentucky and New York have per-mile surcharges. While some owner-operators buy only enough fuel to get through surcharge states, this practice can backfire, depending on the actual cost of the fuel in each state. There may be times when buying more fuel in a surcharge state is more economical.

Part of the challenge in smart fuel buying is keeping up with changing surcharges and taxes; Georgia, Massachusetts and New York revise their fuel taxes quarterly, and North Carolina revises its own semi-annually.

Other fuel-buying costs depend on how your fuel taxes are managed. Most leased owner-operators depend on a carrier to collect and distribute fuel taxes. If you’re leased and your carrier handles your fuel taxes for you, simply look for the cheapest pump prices. Some carriers charge a fee for this, and some pay simply by averaging the mileage of their entire fleet. If your carrier does that, and you average a better per-gallon average than the fleet, you could be paying more tax than you actually owe; for this reason, some make the case that it’s always best for an owner-operator to handle his/her own fuel taxes.

Whatever the case, a good lease will itemize all charges, including fuel taxes and how they are assessed. If your settlements do not reflect what is stated in your lease, you should ask for clarification and, if necessary, look for an alternate method of paying your tax. Not all carriers, however, allow leased operators to opt out of their system, so make sure you understand how the carrier handles IFTA before signing on.

You must get your own IFTA account to do your own fuel tax reporting, whether you do it yourself or through a third party. You do not have to have your own operating authority to get an IFTA account, but independent owner-operators must have such an account in their base plate state and be responsible for quarterly reporting. You also can use knowledge of state fuel taxes to smooth out your cash flow and avoid paying surcharges or large tax bills.

GETTING WITH THE PROGRAM

Owner-operators often can save an average of 6 cents per gallon or more when they are able to participate in major carriers’ discount fuel networks, according to ATBS. If your fleet has a fuel-optimizer program, use it. An optimizer program helps an owner-operator plan a trip based on fuel prices and locations in the carrier’s fuel network. Fees for using such networks have become rare thanks to competition for drivers.

Owner-operators are well advised, however, to pass up network fuel stops that are too costly, are too far off route, sell inferior fuel, are dangerous or poorly maintained, or are perceived as a profit center for the carrier at owner-operators’ expense. If you have concerns about a stop on the fleet network, respectfully bring them to the fleet’s attention.

The National Association of Small Trucking Companies offers members the opportunity to tap into the association’s directory of fueling stops to find the lowest prices. Another of the organization’s tools is a daily fuel hedge; each weekday NASTC takes a reading of OPIS wholesale rack prices from about 400 fuel locations that becomes the cost basis for the next day’s fuel purchases. Drivers get a text-message with an alert that lets them know whether the next day’s prices will be more or less than current.