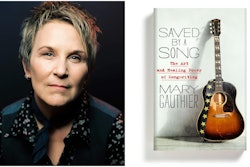

The latest in “Long Haul Paul” Marhoefer’s “Faces of the Road series features …

Mary Gauthier

Mary GauthierMary Gauthier: Folk singer

Past jobs: Lawn care provider, Short-order cook, Chef, Restaurateur

“Paul, your logs are atrocious. You’re going to have to come in on Saturday and fix them. I’m not going to prison for you, dude.”

It was a common refrain from my terminal manager, Kevin Glass, back in the paper log days of late 2010. Not being above the practice of civil disobedience through discrepant clerical entry, it fell on me sometimes to make revisions, once the logs were audited internally. I won’t incriminate myself further as to how often these sessions took place, but let’s just say I always felt a little guilty every time I passed a pulpwood truck. Strangely, though, it seemed we would work on log corrections for about 20 minutes, and spend the remainder of those mornings Youtube-ing our favorite Americana artists. It was discovered that we both were fans of a new-ish female songwriter who was getting a lot of play on the Sirius XM Outlaw Country Channel 60, one Mary Gauthier.

“Check this out,” he’d say, as her Youtube channel rolled to a talking-blues number called “Falling Out of Love,”

It’s a cheap hotel, and the heat pipes hiss.

The bathroom’s down the hall , and it smells like piss.

It was raw. It was gritty. It was right as rain. Finding another Mary Gauthier fan in 2010 Richmond, Indiana, was an apparent cause for celebration. The gravel-voiced Kentuckian pulled a fruit jar from his file cabinet, took a sip from it, and handed it to me. While I’m not altogether certain whether Gauthier (pronounced go-Shay), a recovering alcoholic now 27 years sober, really intended her songs to be listened to in this manner, it was clear that she was getting me out of a lot of remedial paperwork, and the shine was the smoothest I had ever tasted. She had me at piss.

Nor would I have dreamt that one day I would have the honor of interviewing “The Queen of Country Noir” for Overdrive magazine about her most lauded album to date, “Rifles and Rosary Beads,” an album co-written with military veterans in conjunction with SongwritingWith:Soldiers, a program birthed by Austin-based singer-songwriter Darden Smith and his longtime partner, Mary Judd, who, for her part, has compared the trove of songs the project has spawned to the Civil War diaries. Mr. Smith explained to me that the process borrows from the oral tradition, pairing soldiers with some of the top songwriters in the business.

Names like Radney Foster, Jay Clementi, Georgia Middleman, Gauthier, Darrel Scott, Gary Nicholson and Smith himself have graced the retreats. Politics are set aside. The only agenda is the song. Once the soldier’s story is ascertained , as Gauthier explained to me, “the songwriter’s job is to disappear” from the narrative. In so doing, Smith and Judd, with their dream team of songwriters, have midwifed a genre unlike anything this gear-jammin’ music junkie has ever heard, making an art form of collaboration, consecrated to the task of transcribing the traumas and truths of those among us who have sacrificed the most.

I keep going back to the songs from the retreats, now numbering 27 albums. They range from the outrageously funny “Involuntary Erection,” by Gary Nicholson and veteran Palermo Deschamps, to gritty country blues masterstrokes such as “Ink,” by Jay Clementi and veteran Will Kimbrough. The songs can be heard and purchased digitally for whatever price you name at this link.

For Smith and Judd, the fulfillment comes through finding connections and commonalities with the women and men who served, and the ability to go beyond surface differences. “It’s about the look on the soldier’s face,” he says, when someone, who “hours ago was a complete stranger,” entrusts the writer with their story. They then, together, turn it into a song the soldier will have for the rest of his or her life.

“If you look at me, you can probably tell who I voted for,” he jokes. “Some of these soldiers are the most conservative folks I’ve ever met; but that’s all surface stuff.” The songs, and what they represent, are a “model for our culture at large,” he said.

And, for this driver’s dollar, they possess a scope and import so Homeric that it seems like an outright crime they’re not more widely known. Enter Mary Gauthier.

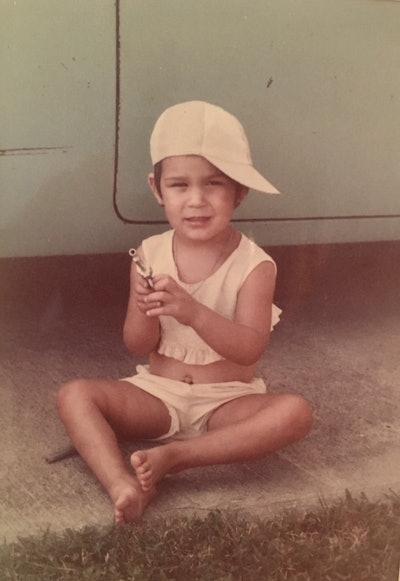

Gauthier at age four

Gauthier at age four“I was mowing lawns by the time I was ten, just to get enough money to buy some weed.”

Born March 11, 1962, in New Orleans and given up by her birth mother to St. Vincent Infants’ Asylum, now regarded as one of the most haunted buildings in the French Quarter (ghost tours still available), Mary was eventually adopted at the age of one by Barbara and Joe Gauthier, a dietician and geologist respectively. Addled by an attachment disorder which frequently plagues orphans, young Mary was bright, precocious even, and hardworking, though troubled.

“I was mowing lawns by the time I was ten, just to get enough money to buy some weed. I had to pretend to be a boy,” she told me by phone. At the ripe old age of 15, she stole her adopted mother’s car, leaving home for good., which she later chronicled in her mostly autobiographical song “Drag Queens and Limousines.”

Several cycles of rehab, recovery, relapse and jail would, like the ghosts of St. Vincent, hound her for the next 20 years; still, the work ethic remained. She would complete five and a half years of college, quit … then transition to culinary school. By the time her first album, “Dixie Kitchen,” was released, she had an ownership interest in three restaurants in Massachusetts, which she would later sell to become a full-time musician.

“Selling the restaurants was terrifying. But I fell out of love with them,” she says. “I had to move on. Staying was going to kill me.” In the midst of all this professional success, on the night her first restaurant opened, she wound up in a Boston drunk tank, found recovery, and got sober.

A new mental space was created. She wrote her first song at 35. It was well-received at open stages, and the metamorphisis into a full-time artist began. The veteran chef would eventually make it to Nashville by way of Austin, displaying a knack for surrounding herself, like so many ingredients, with the best people in the business. She would go on to write for the legendary Harlan Howard Songs; and, at the recommendation of recovery brother Ray Wylie Hubbard, would find the full possession of her voice in that 2009 collaboration that garnered her a national audience, “Mercy Now,” produced by Austin-based Americana maven Gurf Morlix, whose discography includes clients such as Hubbard, Lucinda Williams and Robert Earl Keen.

By 2010, off-duty truckers a thousand miles from Austin were huddling over computers in nondescript warehouses on Saturday mornings, sipping the aforementioned moonshine, taking in every dark and dangerous word.

Jerry Novak, retired Air Force veteran and longtime cow hauler said he “shed a tear” the first time he heard “The War After the War” on satellite radio.”There’s not a warrior out there who’s not scarred in some way, shape or form,” he told me in a phone interview.

Gauthier’s dexterity with things dark made her “an inspired match for the Songwriting:withSoldiers program,” according to Sirius XM Outlaw Country’s Meredith Ochs. “There’s an emotional directness to her lyrics — she can cover really dark subject matter in a plainspoken way. It’s a great approach to help veterans express what they’ve seen and endured. And the songs should give civilians a better understanding of what soldiers experience. They sacrifice so much for the rest of us. We’re failing them if we don’t do whatever we can to help them when they come home.”

For Gauthier, one of the great surprises of the retreats was learning just how much we are failing them. “You’ve got one half of one percent of the population carrying the load for everyone else. Some of these soldiers are being deployed 10 or 12 times; so there’s trauma upon trauma. That helps explain why 22 of them a day are committing suicide.”

One veteran who came to SongwritingWith:Soldiers at the urging of his wife, Retired Army Sargeant Josh Geartz, was no stranger to the veteran suicide epidemic. Having attempted it once himself in 2014, he had already made his own second date with death. It would be November 7, 2015, the anniversary of his best friend’s death, just weeks after the retreat.

In 2000, Geartz, an MP stationed then in Germany, was nearing the end of his shift. A call came in: “accident on Autobahn 45 involving a tractor-trailer and an unspecified amount of cars.”

“On the Autobahn, some of the exits are 45 miles apart,” he says. “A trucker had missed his exit, and was attempting an illegal three-point turnaround in the middle of the road.”

Geartz, the first officer on the scene, came up on the very same dark gray 300 Series BMW he had jumped out of just hours before. It had been driven by his best friend, PFC Thomas Faulk, who was now unresponsive. Earlier in the day, Geartz had orchestrated a surprise reunion between Faulk and his wife Tawanna, herself a soldier, at the base. It was the first time the couple had seen each other in a year. Faulk could not have been more joyful. He would then beg his best friend to accompany them to dinner.

Geartz declined. “Go be a husband and wife.”

“Come on Josh, we’re family,” Faulk would contend.

Geartz finally consented, reluctantly. As the car was about to exit the base, Geartz said, “I can’t do this. You two need time to yourselves,” and got out of the car. Now, hours later, his friend was gone, his friend’s wife in critical condition.

The what-ifs would come to haunt the MP. Maybe if he had accompanied them he would have been driving, and could have avoided the collision. Maybe the seconds of indecision before he finally declined made all the difference and prevented his friend from passing through that measure of time and space before the trucker’s reckless decision to turn around in the middle of the Autobahn. Still, there was nothing the MP could do but soldier on.

Five years later, on the very last night of his deployment, just hours from seeing his family, Geartz was now a in Abu Ghraib. Now a Sergeant, his Humvee was hit by a roadside bomb, leaving him partially paralyzed with holes in his ear drums, injuries to the brain and spine, chronic blood clots. He would be in constant pain for the rest of his life.

Upon returning home, the only hospital nearby that had the proper equipment to monitor the extent of injuries he had sustained was the Buffalo Women’s and Children’s Hospital. He had a long, hard road to recovery ahead of him. The minutes passed like hours. He asked his wife Lisa to bring him his Hohner Blues Harp, key of C. The soldier had played harmonica since he was eight. Being separated from his harp “was like not having my wedding ring on,” he says.

He had spent years learning from the masters, and he did it the old-fashioned way: play, stop, rewind, play, stop, rewind over and over again until you get it right. He was all Stevie Wonder for a while, then Paul Butterfield, then James Cotton, then Charlie Musselwhite. There, throughout the ward of The Buffalo Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Sergeant Joshua Geartz could be heard, playing the blues. He asked the nurses if it was too loud. “They laughed and said, ‘Not loud enough.'”

Still, upon his release, the two events in his military career had conflated themselves into one ineffable ball of pain. Now immobilized, there was nowhere to run now from the what-ifs — not even to the blues. He began to drink.

“Look, I’m a lesbian leftist.”

Ten years later, his good wheelchair in the shop, Geartz was propelling himself uphill one Saturday morning in an old-fashioned wheelchair at the Carey Institute for Global Good, a retreat center nestled in the Northern Adirondacks. His wife Lisa had told him he was going for the first time just one day before.

“She didn’t want me to have time to talk myself out of it,” he says.

The thought of jamming with some world-class musicians intrigued him, though. He still loved music, even more than he had come to hate his life. He and Lisa had a son. He owed it to the boy to make one last try. The incline to the retreat center was long and steep. Geartz was pissed. Lisa was walking alongside of him, knowing better than to offer him help. His service dog Koda, a loyal pit bull, flanked his other side. Mary Gauthier, viewing this scene through the window of the center, coffee cup in hand, called out to Smith, Judd and the rest of the writers. “He’s mine.”

The veterans were introduced to the songwriters and treated to a concert. Each musician sang three songs. Gauthier’s set ended with “Mercy Now.” Mary Judd then polled each participant individually. When asked which songwriter he’d like to work with, “I think I’d like to work with Mary” was Geartz’s response. “She just smiled real big,” he recalled.

The two clicked famously, though they couldn’t be any more different. “Look, I’m a lesbian leftist,” Gauthier would tell me; and Geartz, for his part, a registered Independent, with right-center political sensibilities. Still, in that place wherein lies “the dearest freshness deep down things,” as Gerard Manley Hopkins put it, where the only agenda was the song, Geartz found himself telling Gauthier things about himself he had never told another human being. He would later tell New York Times op-ed contributor Margaret Renkl, “That’s kind of where the flicker of hope started. Right there.” And together they crafted a song, “Still on the Ride,” which landed them on the stage of the Grand Ol’ Opry.

I shouldn’t be here. You shouldn’t be gone

But it’s not up to me who dies and who carries on

I sit in my room and I close my eyes

Me and my guardian angel, we’re still on the ride

[Catch a video run through the song via this link.]

It was Geartz on his Hohner Blues Harp, this time in the key of A. Gauthier, on her exquisitely weathered 1950 Gibson J-45, the model they called the “work horse.” Others from the retreat were on hand to join in. Dry eyes, that night, were in short supply. Geartz’s own metamorphosis to an artist and advocate had now begun.

Still, Gauthier shuns the notion that she’s some “aloof and untouchable star, standing on a mountaintop, healing the soldiers.” If anything, she and and all the soldiers who participated in the project are “repairing each other,” she says.

“Mary never got a chance to have a family of her own,” retired Army Sargeant Josh Geartz told me. “So we just made her part of ours.”

The album can be purchased via Gauthier’s website, or most anywhere online music is sold.