Updated September 27, 2021, as part of Overdrive's series of lookbacks attendant to the magazine's 60th anniversary. This story, originally published in 2011, charts broad current in the history of the owner-operator business model in all its complexity decade by decade through the first full decade of this century. Help us finish the history: a decade or two down the road, how will we look back at the 2011-2021 period when it relates to owner-op history? Drop us a comment below this story or reach out directly to Editor Todd Dills.

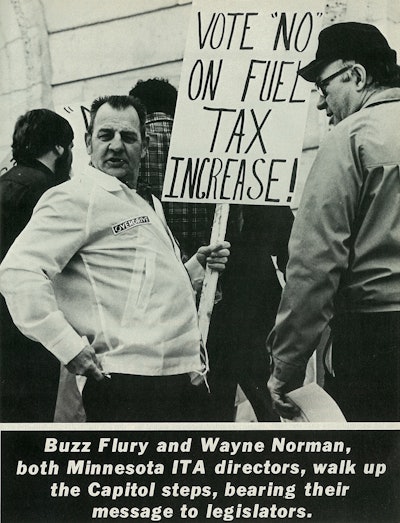

Independent Truckers Association state chapter heads Buzz Flury (left) and Wayne Norman protest high taxes on the steps of Minnesota’s Capitol. The photo ran in Overdrive’s July 1979 issue, which reported on trucker strikes in June.

Independent Truckers Association state chapter heads Buzz Flury (left) and Wayne Norman protest high taxes on the steps of Minnesota’s Capitol. The photo ran in Overdrive’s July 1979 issue, which reported on trucker strikes in June.

The owner-operator of yesteryear struggled to prosper amid a complex web of Teamster pressures and over-regulation. Shutdowns and other conflicts lined the highway that led to today’s climate in which the self-employed contractor is integral to the industry and able to operate with much greater independence. From fighting for enhanced freedom to haul in its early days to stressing smart business practices later, Overdrive has championed the owner-operator’s concerns.

1950s and ’60s: Fast track to a golden age

When Overdrive launched in 1961, trucking was dominated by the Teamsters union. Even in the unregulated area, where owner-operators and small fleets had hauled commodities deemed exempt from price regulation since the industry’s infancy in the 1930s, unions exerted their organizing pressure. Overdrive founder Mike Parkhurst is said to have been driven to launch the magazine in part by a personal affront chronicled in historian Shane Hamilton’s 2008 book “Trucking Country: The Road to America’s Wal-Mart Economy.”

[Related: Overdrive's first, September 1961 issue in full]

Then owner-operator Parkhurst was at a receiver in Mansfield, Ohio, when “a Teamster organizer informed him that he would have to pay union dues to unload his produce,” Hamilton wrote. Along with the complicated regulatory structure of the Interstate Commerce Commission, the Teamsters, Parkhurst believed, “had ‘strangled the healthy growth of the free enterprise system.’”

The options for owner-operators wishing to haul regulated freight prior to the mid-1950s were limited to finding one of the relatively few regulated carriers who leased owned and operated equipment. Most operators of the time carved a niche in produce markets.

No motor carrier authority was necessary, thanks to agricultural interests securing an exemption from price and lane regulation in the first Motor Carrier Act in 1935, which directed the ICC to regulate the movement of any non-exempt freight. As a result, “a lot of your early owner-operators – especially in produce – come from farms,” said Brian Kimball of the Kimball Transportation brokerage (whose family is pictured, around 2011). “They’re hard workers. They have a knowledge of the machinery – they could repair their own equipment.”

The Kimballs around 2011.

The Kimballs around 2011.

Kimball’s father, Ed, hauled produce with his five sons in Ed Kimball & Sons Trucking. Before that he leased to different produce-trucking outfits in Florida and, by the late 1950s, typically hauled refrigerated commodities back under trip-lease arrangements. Enabled by legislation enacted in 1957, trip-leasing (running under a regulated carrier’s authority for a single trip agreement) expanded options for owner-operators. Deadhead miles were reduced as obtaining regulated backhauls became more common.

Through the 1960s and into the ’70s, in spite of the limitations to entry in the regulated market, a small-town Indiana boy could buy a truck and “make a decent living” just trip-leasing with carriers, said consultant Jay Thompson. Thompson and his brothers did just that.

[Related: What came before the CDL? 18 years old and hauling in 1917]

After repeated scandals among Teamsters leadership under Jimmy Hoffa in the 1960s disillusioned many drivers – and more carriers began to view independent owner-operators more favorably – the average income of the self-employed driver rose above the average wage earnings of employee drivers for the first time nationally.

Read more in Overdrive's weekly 60th-annversary series of lookbacks on trucking history, and that of the magazine itself, via this link.

Read more in Overdrive's weekly 60th-annversary series of lookbacks on trucking history, and that of the magazine itself, via this link.

The exempt trucking market was “the most cutthroat business there ever was,” saidTodd Spencer, executive vice president of the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association. “Brokers stiffing truckers was routine.” With lax ICC regulations governing carrier leases with owner-operators, many of those who leased owner-operators prior to the late 1970s had the upper hand, he said.

The 1970s: The road to deregulation

As owner-operators increased in numbers, so did their recognition within the industry. Parkhurst in the 1960s launched a national trade group, the Independent Truckers Association, and later the Roadmasters.

Avoca, N.Y.-based owner-operator David A. Margeson, who hauled exempt potatoes, was a Roadmasters member. He recalled that the organization put the owner-operator “on Main Street. Up to that time there’d been no recognition of owner-operators.”

“For the first time in history, a simple thing such as a magazine brought owner-operators together from every aspect of trucking with common interests and common goals which could be heard and shared with other truckers from coast to coast. In the days before computers and Internet services, this was a connection unheard of.” – David A. Margeson, with his 1985 Mack Superliner

“For the first time in history, a simple thing such as a magazine brought owner-operators together from every aspect of trucking with common interests and common goals which could be heard and shared with other truckers from coast to coast. In the days before computers and Internet services, this was a connection unheard of.” – David A. Margeson, with his 1985 Mack Superliner

He also recalled the frustration of independents, who felt the ICC had outlived its original intent. “When it was first formed and set up regulated routes, carriers had to obtain rights so that no area of the country would be left out of the picture,” Margeson said. After trucking was well-established across the nation, “to the independent, it seemed like we didn’t need that system anymore. Areas would get taken care of without it – it seemed like a hindrance to interstate commerce to have rights to a particular area.”

Owner-operators leased to regulated haulers, too, banded together to force carriers and the Teamsters to recognize them. In the Midwest, the Fraternal Association of Steel Haulers formed to fight for the union’s consideration of the “unique economic interests” they had as owners of their “own expensive equipment,” Hamilton wrote. They launched strikes in 1967 and 1970, feeling as if they were paying dues for little representation from the union.

As union disillusionment spread, volatile fuel prices and runaway inflation provided a key mobilizing force for industry change. During the independents’ shutdown during the 1973-74 Arab oil embargo, a new owner-operator organization emerged, the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association. OOIDA focused on regulation of carrier leasing practices.

As more all-owner-operator carriers emerged and operator numbers surged in the 1970s, abuses of leased drivers were rampant, said Charles Myers. Myers was a district supervisor with the ICC beginning in 1976 in Harrisburg, Pa.

Myers recalled the typical owner-operator complaint in which an individual sets up an office, promises freight to “all these owner-operators who commit to running for him. He’d run them for a while and never pay them,” Myers said. “You’d have to come back and make a case for violation of the leasing rules of the time. Most of the time they’d just get an injunction and shut the guy down and try to get restitution for the owner-operators.” Penalties were small, so repeat offenders were common.

Congressional hearings in the ’70s exposed such practices, in part at the instigation of OOIDA. In 1979 the ICC adopted the Truth in Leasing regulations, adding “transparency to the relationships” between leased owner-operators and their carriers, Spencer said.

After a series of unsuccessful bills throughout the ’70s to allow owner-operators to compete in the regulated freight marketplace, conditions climaxed in the late 1970s. The leasing regs were hitting the books. Independents were shutting down in protests prompted by 1979’s fuel shock.

As Hamilton recounted it, the unstable economic environment was seized upon by Senator Ted Kennedy, then eyeing the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination. Kennedy and others pitched wholesale trucking deregulation as a solution to the problems of independent owner-operators and price inflation of consumer goods. Deregulation was achieved when President Jimmy Carter pushed through the Motor Carrier Reform and Modernization Act of 1980.

The 1980s and ’90s: An industry transformed

The new environment did not immediately translate to more pay for independents. Unrestricted as to lanes, areas of operation and freight, carriers with capital to invest in new trucks and drivers expanded quickly. As a guy with one truck, said Margeson, “we were still out of the picture, because what can we do with one truck?”

Many have characterized post-deregulation as a “race to the bottom” in terms of rates and driver pay, said Spencer. “The rising stars rejected the mold that trucking had evolved to,” largely a patchwork of regional businesses. “Everyone was going to be a national carrier,” he added. “They weren’t interested in hiring drivers who only wanted to work in regional areas with good pay.”

It’s one reason OOIDA didn’t support deregulation. “All we had to do was look at the already unregulated segment of the industry,” exempt hauling, to see where the rest of the industry would go if deregulated, Spencer said.

All the same, as competition soared throughout the ’80s, the owner-operator’s role was being established. Efficient single-truck businesses became more attractive to carriers. All-owner-operator “non-asset-based” fleets multiplied.

In the intervening years, the rise of computing and communications technology eased accounting and registration procedures. Load information became available online by the end of the century. By the early ’90s, nearly every state was a part of both the International Registration Plan and the International Fuel Tax Agreement, eliminating much paperwork. Prior to IFTA, Margeson said, “we had to send in a quarterly report for each state we ran. If we ran 32 states in a quarter, we had to make out 32 quarterly reports.”

As the industry changed, so, too, did Overdrive. When Parkhurst sold the magazine in the mid-’80s to Randall Publishing Co., the company refocused the content toward helping readers refine their business practices.

2000s up through 2010: The ‘enforcement industry’ arises

When historians look back on the first decade of the 21st century in trucking, no doubt the fuel-price shocks and the 2008 economic meltdown will play large. But some owner-operators and leasing carriers were prepared for both, having experienced variations on those themes for years.

What might figure more largely is an “industry,” as Spencer called it, surrounding safety enforcement. Since the Motor Carrier Safety Assistance Program emerged in the early ’80s, throwing trucking enforcement money at states – “well over $300 million a year" as of 2011, he said – intrusions into owner-operators’ businesses in the name of safety have increased.

That extended to truckers’ day-to-day relationships with law enforcement. In spite of the long-held outlaw image of the independent trucker of the ’60s and ’70s, Spencer said, “at night, the best friends a cop could have were the truck drivers. The truckers would be the first people to stop and help” in an emergency.

Margeson said the relationship “went sour from about 1985. About the only thing you could get stopped for back in the day was speeding. If you got stopped for that, they might ask you for a log book. Other than that, your DOT checks – then called ICC checks – came in the fall of the year,” and again in the spring. Today, Margeson added, it’s not unusual to get checked two or three times on a short run. “They do it in the name of safety, but now it’s more of a money deal for the states.”

Safety ratings based on compliance reviews became the norm for carriers when the SafeStat program emerged with the new Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration in 2000. The events of 9/11 increased scrutiny of all drivers, whether hauling sensitive freight or applying for a general-freight lease. SafeStat’s successor, the 2010-instituted Compliance, Safety, Accountability program, took safety rating to an unprecedented level, providing monthly updates to a carrier’s safety rankings based on inspection and crash data.

At that time, the FMCSA even planned to put individual drivers under a similar public ranking system. True independents looked to receive possible dual numerical rankings as both carrier and driver.

Challenges abounded, both regulatory and otherwise: multiple hours-of-service revisions, onboard recorder mandates, tighter health restrictions for CDL holders, increasing congestion, long wait times at shippers and receivers, fraud among fly-by-night brokerages.

Partly for some of those reasons Marion, Ind.-based owner-operator Mike Long traded his independent business model for the safety net of leasing to a carrier, he said. In 2008, he leased to Landstar.

Long echoed many operators when he said he wouldn’t trade a business he calls “his life” for anything. “My dad made money in his day,” he said. “But you can still make money today, taking everything into consideration. There’s no way I’d want to run a single-rear-axle gas-engine truck on springs, no power steering, no A/C on U.S. 40” across the country.

“Certainly trucking can be a hard life,” says Spencer, “but some of the most wonderful people in the world are attracted to this business – it attracts people who want to work hard” and succeed. For that, the owner-operator career remains a prime example of the nation’s opportunities for self-employment.

[Related: A brief history of trucking in America]