Part 2 of this series covers 15-liter engines and their recent advances in fuel economy. See it here. Part 3 offers tips on how to choose between the two. Click here to read it.

In today’s world of $4 diesel, spec’ing a 600-horsepower engine demands a business case in which the requirement for power and torque is an absolute necessity – usually heavy-haul or some vocational applications. Otherwise, it’s a vanity purchase for those with money to burn.

Meanwhile, today’s modern technology has enabled engines of both sizes to deliver relatively high horsepower and torque while turning in fuel economy numbers unachievable a decade ago.

Why 13-liter engines rule the market

The trend toward bigger engines peaked around 2008 or 2009. Among Overdrive readers polled in 2008, those with model year 1995 or older trucks had engines averaging 12.7 liters. Those with 2001 or newer had engines averaging 13.9 liters. The fall of 2008 saw diesel prices spike above $5 a gallon in California, and the industry has been more fuel-sensitive ever since.

Mack’s 13-liter MP8 engine has a horsepower range from 415 to 505 hp and torque ratings from 1,460 to 1,760 lb.-ft. It’s 16-liter MP10 diesel has five specialized power ratings ranging from 515 to 605 horsepower.

Mack’s 13-liter MP8 engine has a horsepower range from 415 to 505 hp and torque ratings from 1,460 to 1,760 lb.-ft. It’s 16-liter MP10 diesel has five specialized power ratings ranging from 515 to 605 horsepower.In more recent years, 13-liter engines have emerged as the favorite spec for new heavy-duty trucks. More of Kenworth’s line-haul customers are switching to 13 liters because of weight reduction and fuel economy, says Kevin Baney, chief engineer for Kenworth Trucks.

“With our Paccar 13-liter MX engines today, we can offer them 385 horsepower all the way up to our 500-horsepower Cummins option, which will debut in January,” he says.

Navistar saw the trend toward 13-liter power coming some years ago as customers became more focused on weight, payload and fuel efficiency, said Steve Gilligan, vice president of vocational and product marketing. “That’s what drove us in our development of our MaxxForce 13,” Gilligan said. “The added weight of emissions-related equipment and fluid is offset by the 13-liter engine.”

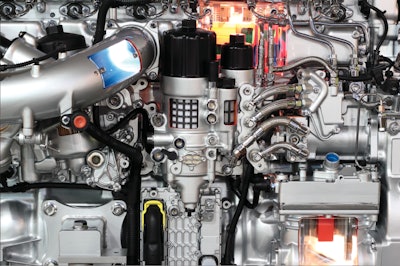

Daimler’s Freightliner and Western Star brands supply either 13- or 15-liter diesel engines, including this DD13, from its in-house Detroit lineup. Detroit also offers two big-bore diesels: Its 15-liter DD15, offering 455 to 505 horsepower, and its 16-liter DD16 with a power rating of 475 to 600 horsepower.

Daimler’s Freightliner and Western Star brands supply either 13- or 15-liter diesel engines, including this DD13, from its in-house Detroit lineup. Detroit also offers two big-bore diesels: Its 15-liter DD15, offering 455 to 505 horsepower, and its 16-liter DD16 with a power rating of 475 to 600 horsepower.Jennifer Rumsey, executive director of heavy-duty engineering for Cummins, notes that most of what’s marketed today as 13-liter engines actually have displacements ranging from 11.9 to 13 liters. The popular Cummins ISX15 is an integrated driver-friendly engine suited for long-haul, Rumsey says, while the Cummins ISX12 – which shares common components with the ISX15 – has been optimized for regional hauling and less-than-truckload operations, as well as vocational applications such as dumps and mixer trucks and fire and emergency vehicles.

“The older thinking was to buy a larger engine and run it easy – it’ll get good fuel efficiency and last forever,” says David McKenna, powertrain sales and marketing manager for Mack Trucks. “The thinking used to be that if a 5-pound bracket was good, a 10-pound bracket was better. We can now meet customer needs regarding power while improving fuel economy without sacrificing engine life.”

McKenna says today’s most common horsepower rating for a 13-liter engine is 415, or 32 horsepower per liter. Conversely, 15-liter engines work out to 450 horsepower, or 30 horsepower per liter.

International’s MaxxForce 13 features four power ratings ranging from 410 to 475 horsepower. The company’s MaxxForce 15 will be available for a limited time into 2013 with ratings from 435 to 550 horsepower – but the bulk of the company’s big-bore offerings will be covered by its addition of the Cummins ISX15 this month.

International’s MaxxForce 13 features four power ratings ranging from 410 to 475 horsepower. The company’s MaxxForce 15 will be available for a limited time into 2013 with ratings from 435 to 550 horsepower – but the bulk of the company’s big-bore offerings will be covered by its addition of the Cummins ISX15 this month.“There is a perception that bigger is better for a long-life engine – I strongly disagree,” he says. “Our 13-liter Mack MP8 engines have accumulated a phenomenal amount of miles. During disassembly and inspection, we were more than pleased with our design criteria being met easily based upon million-mile wear observations.”

Going even smaller, Mack now has customers using its 11-liter MP7 who are seeing a documented 2 percent fuel efficiency improvement compared with a 13-liter and 3 percent compared with a 15-liter, McKenna says. “Correct engine sizing is the base from which to optimize performance,” he says. “If you start from the wrong base, nothing else you do will be correct, and maximum optimization will never be achieved.”

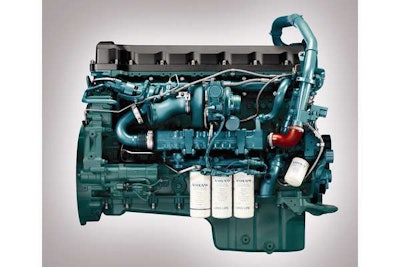

Ed Saxman, drivetrain product manager for Volvo Trucks, says Volvo had a 12-liter engine that it increased to 13 liters due to power density so that the top rating could be increased to a full 500 horsepower with 1,750 lb.-ft. of torque. “We also introduced our 11- and 16-liter engines to be able to offer additional lighter-weight and higher power options,” he says.

The Paccar MX-13 engine is standard in Kenworth and Peterbilt on-highway and vocational trucks. The MX-13, which debuts in January, is offered in 385-horsepower all the way up to 500-horspower.

The Paccar MX-13 engine is standard in Kenworth and Peterbilt on-highway and vocational trucks. The MX-13, which debuts in January, is offered in 385-horsepower all the way up to 500-horspower.Gilligan contends that the market shift isn’t defined wholly by displacement for displacement’s sake. “What you’re seeing more and more, in terms of engine technology, is a smaller-displacement, lighter-weight and more-efficient engine delivering the same level of horsepower that was only achieved in the past with a 15-liter engine,” he says. “Average horsepower has shifted only slightly over the past 10 years. The same fleets that were running 430-horsepower engines a few years ago may have shifted peak horsepower upward, but torque is relatively unchanged and is well within the efficient operating range of 13-liter engines.”

Larger-displacement engines can offer higher torque without adversely increasing peak cylinder pressure, Saxman says. “Horsepower and displacement are less connected than many think,” he says. In Volvo’s case, the average delivered horsepower of the 13-liter engine in its tractors has been slightly higher than the average horsepower of the 15-liter supplier engine that it delivers. “The same was true for our 12-liter, which preceded the 13-liter.”

Volvo uses similar designs for both displacements, and the design concept can be used across three displacements, but some part sizes may vary out of necessity. “While one might surmise that a larger displacement means more robust part design, that is not necessarily true,” Saxman says. “The Volvo D13 connecting rod is more robust than those of other larger-displacement engines.”

Twelve power ratings from 375 to 500 hp are available for Volvo’s 13-liter D13 engine. Volvo’s 16-liter D16 engine features three ratings ranging from 500 to 550 horsepower.

Twelve power ratings from 375 to 500 hp are available for Volvo’s 13-liter D13 engine. Volvo’s 16-liter D16 engine features three ratings ranging from 500 to 550 horsepower.McKenna says that at first glance, the displacement difference in today’s North American engines is only 2 liters, raising the question of why both with two engine sizes. “I think the answer is in the efficiencies that can be realized using the optimal power density of each engine,” he says.

McKenna believes Mack’s MP7 at the 32-horsepower-per-liter power density has proven to be the right balance for engine fuel economy and performance versus power output. “Potentially, the larger-displacement engines should see the power density number increase, as the larger mass platform can offer greater strength in the block and crank areas,” he says.

If an acceptable power density from each engine is maintained, the smaller-displacement engine should get better fuel economy since it has lower internal friction, less reciprocating mass and a lower weight. “Reducing tare weight alone contributes to better fuel efficiency,” McKenna says. “Right-sizing the engine is extremely important. Bigger is not always better.”

In addition to weight savings, another 13-liter advantage is packaging. “We can put 13-liter engines into a shorter BBC tractor with a shorter hood,” Baney says. “That gives drivers both improved maneuverability and visibility.”