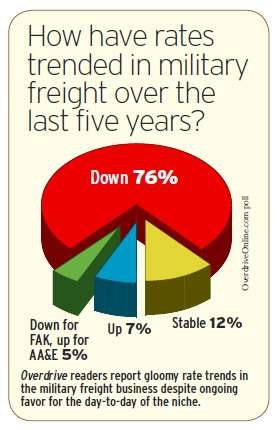

“Competition is up,” Kiah says, for both security-sensitive arms, ammunition and explosives – or AA&E, typically the better-paying type of military freight – and general government freight (FAK). Like any kind of general-type freight, he says of the latter, “everybody’s out there trying to make the best bid they can possibly make to be profitable.”

Kiah isn’t alone in his assessment. With the federal government increasingly outsourcing its logistics, it’s harder to break in to the military hauling niche, and those who’ve made it find that rates aren’t what they used to be.

The Department of Defense “does a great job of keeping prices competitive,” says Ted Alling, chief executive officer of Access America, a Chattanooga, Tenn.-headquartered brokerage that deals with DOD shipping sites for general freight. Alling says Access America also does some business with Menlo Worldwide, the prime contractor that manages 44 percent of nonsecurity-sensitive domestic freight shipments.

So strong is the competition today that three out of four owner-operators report rates for military freight have dropped over the last five years, according to a survey of Overdrive readers.

[Related: How to get access to military freight]

Some longtime owner-operators blame the federal Defense Transportation Coordination Initiative for that. The DTCI brought Menlo onto the scene in 2007 to cut shipping costs as a third-party logistics manager contracted by the Surface Deployment and Distribution Command. Commercial practices “not normally embraced by the government” have been brought to bear in order to produce the savings, says SDDC Public Affairs Officer Mitch Chandran.

At the time DTCI was being implemented, Landstar-leased owner-operator Bryan Manley says he commonly ran Menlo loads out of Fort Bragg, N.C. After the third-party logistics firm came on board under the initiative, “the loads were less frequent and paid less.”

Mitch Chandran, public affairs officer for SDDC, says working with Menlo has exceeded SDDC goals for transporting domestic military freight more efficiently. “The program has also improved visibility, updated antiquated IT systems and fostered positive partnerships with the commercial sector while streamlining” domestic movements.

Today, Chandran says, contrary to the beliefs of many owner-operators, the DTCI continues, though there are no plans to expand it further to include other shipping sites. “All sites … that intend to be in the program have already been implemented,” he says, accounting for about 44 percent of all nonsecurity-sensitive military freight more than 150 pounds.

Menlo estimated that as of September 2010 it had “achieved $167.4 million in cost reductions on DOD shipments within the continental United States,” according to an August 2012 report by the Department of Defense Inspector General.

Some readers believe that what’s happened with the rate dynamics is that so many of the entities now involved in arranging for transportation of military freight are “just brokers and don’t own any equipment,” says an owner-operator who prospered during pre-DTCI days hauling freight out of Fort Campbell, Ky., and declined to speak on the record.

It’s not uncommon for transportation officers at sites not covered under DTCI today to “start with the lowest-cost company and work up, even though they can’t provide the best service or sometimes enough equipment for the job,” he adds.

Did you hear the one about the trailer-mounted missile? ...

Hauling freight into and/or out of U.S. military installations, despite rate dynamics, remains a vocation near and dear to the hearts of many a trucker. Drivers report a wealth of experiences dealing with often-young military service members at forts and other installations, hearing stories of patriotic lives in fast flux and hopes for the future.

Stories like this one are legion: Hal Kiah formerly ran in the heavy-haul division of Tri-State Motor Transit, which does a lot of contracting for military freight. He once hauled an unarmed training missile from one base to another, he says. No tarping, no crating — the missile was strapped to a wheeled carrier. Kiah had the servicemen load the missile facing backward.

“It was the first, and only, time that nobody ever tailgated me, followed alongside or even wanted to be anywhere near my rig,” he says. “If they passed me, they wasted no time.”

It also made for good CB conversation. While cruising along, another driver came up behind him and asked what he had on the trailer. “I’ve got this little button up here,” Kiah joked with him. “All I have to do is push the trigger, and it’ll be laying in your lap.”

As for tales of the stereotypical bureaucratic waste and stupidity, Tom Moore recalls a 2010 brokered Menlo-managed load moving from a DOD site in New Jersey to another in Sacramento, Calif.

There were three tractor-trailers on hand, including the Moores’ flatbed, at the pickup location. After some mistakes loading, the Moores were loaded with a “little bitty trailer with a generator on it,” Tom says, taking up 8 feet of length with the trailer tongue. Every other load that came out that day similarly was small.

“I went back into the office,” says Tom. “I said, ‘I have to ask you something. … Together we’ve only got 24 feet of deck filled’ ” between the three units, “ ‘and we’re all going to the same place in California.’ The guy says, ‘That’s the federal government for you.’ ”