The Minnesota Highway Patrol, the lead agency in the state’s truck enforcement activities, didn’t do much good for its reputation among truckers when it used a checklist intended to help determine an operator’s fatigue level.

In 2011, that checklist, also used in limited fashion in at least one other state at the time, was deemed an invasion of truckers’ rights after a successful challenge by the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association.

Statistics and anecdotes suggest that in the wake of the fatigue judgment, some rehabilitation of the inspection program’s reputation has been under way. It’s come via a shift toward mobile traffic enforcement and, perhaps, a willingness of officers to credit professionalism where it’s due.

Mustang’s Truckin’ independent owner-operator Mike Crawford, a past Overdrive Trucker of the Year based in Missouri, has had only one interaction with Minnesota enforcement in recent years in his many trips across the state. “It happened shortly after e-logs,” he says, making reference to an inspection early this year after the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration’s electronic logging device mandate came into play.

Access interactive maps charting state rankings in a bevy of violation/inspection categories via OverdriveOnline.com/CSA, updated with calendar year 2017 data. Also there, download a full 48-state report.

Access interactive maps charting state rankings in a bevy of violation/inspection categories via OverdriveOnline.com/CSA, updated with calendar year 2017 data. Also there, download a full 48-state report.Pulled in at the Interstate 94 scale coming into Minnesota from Wisconsin, he says, “They said, ‘You have electronic logs?’ ” Crawford, who’s put down three million-plus safe miles in an ELD-mandate-exempt 1994 Freightliner, uses the Drivers Daily Log laptop software. He’d brought in printouts of his log book sheets for inspectors, arranging then to email the current day’s sheet to the officer.

“Man, look at these log sheets,” said the inspecting officer, as Crawford recalls. “These things are fantastic. You can actually read them. You can understand them.”

“Having a cop tell me he’s really impressed with my log book,” trucker Kris Santoianni quips, “is like having a cop tell a bank robber he’s really impressed with his bank account.” But happen it did to him as well, likewise at a Minnesota scale house.

That episode was chronicled in part in a February Overdrive feature, in which Santoianni noted the officer took a 30-day dive into his logs. The officer ultimately lauded his professionalism, from the condition of his equipment to the neatness of his paper logs in a likewise ELD-exempt operation.

Minnesota’s standard operating procedure, evidenced in inspection data mined by Overdrive sister data company RigDig Business Intelligence, shows that such fixed-facility inspections are not the most common checks in the Land of a Thousand Lakes.

Rather, as La Crosse, Wisconsin resident owner-operator Rob Hallahan has observed on his frequent runs north and west through the state, most of Minnesota’s inspections are conducted by its 95 full-time personnel and 18 part-time participating local officers away from the six fixed weigh stations, whether at roadside pulloffs built for the purpose or elsewhere during traffic stops.

In 2017, six in every 10 inspections in Minnesota occurred as the result of a roadside stop.

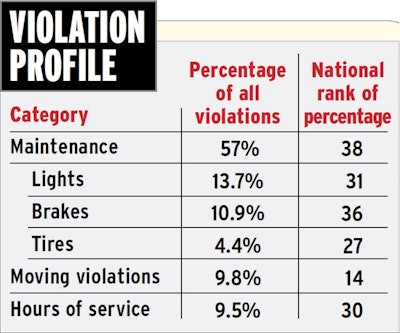

Source: Unless otherwise noted, all numbers, including the Minnesota violation profile here, are based on 2017 federal data analyzed by RigDig Business Intelligence.

Source: Unless otherwise noted, all numbers, including the Minnesota violation profile here, are based on 2017 federal data analyzed by RigDig Business Intelligence.Hallahan says that unlike in many other states, it’s not uncommon to see commercial motor vehicle unit cars camped out in a median monitoring trucks’ speeds or looking for other observable behaviors. “They’ll set up on an exit ramp,” he says, or “pull you over on a Sunday night in the middle of the night to check your log. I’ve seen them doing that, but I’ve never had any issues with Minnesota.”

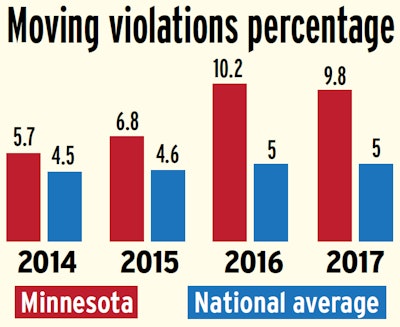

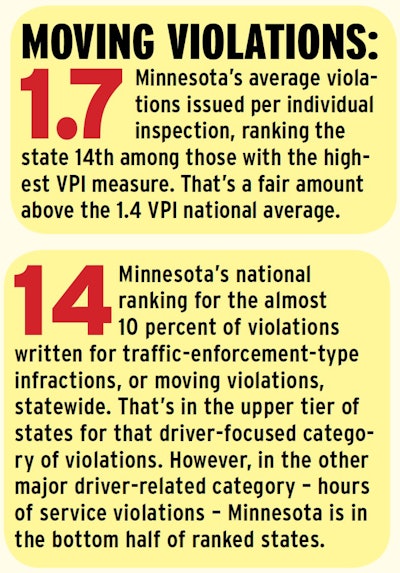

As for violation statistics, Minnesota’s relatively unremarkable outside of an above-average (and rising) ranking among states for its focus on moving violations and its violations-per-inspection average. It’s 14th highest nationally in both categories. Capt. John Olsen, with the lead Motor Carrier Safety Assistance Program agency in the state, the Highway Patrol, believes those numbers are rising with an influx of sworn officers participating in enforcement activities at roadside.

While it’s largely the civilian inspectors working the fixed facilities, “we had a nonpublished court case” in recent years in which “the appellate court said [nonworn inspectors] couldn’t flag trucks at roadside” for inspections, Olsen adds. “That had a tremendous effect on our inspections done roadside, so we’ve had an uptick in our sworn personnel – they’re stopping trucks for moving violations.”

The trends, nonetheless, are borne out by Hallahan’s observations and could point the way toward a broader reality.

After its overreach with the fatigue checklist, perhaps enforcement in the state has gone back to brass-tacks enforcement of on-highway infractions, boosting moving-violations numbers since 2014 by more than 50 percent as of last year, as other violation categories remained relatively stable or on the decline.

Another outcome of the fatigue checklist ruling, Captain Olsen says, was a judge’s order aimed reform of the state’s approach to the DataQs challenge process by which carriers can challenge problem violations incurred during inspections, and have them removed from the carrier’s record with relevant evidence.

“I was not around” during the time of the fatigue checklist, Olsen is quick to note. But he views it as a positive that the lawsuit’s decision eventuated in the judge requiring an appeals panel for DataQs challenge reviews made up of both state enforcement and industry representatives. “Every once in a while I hear horror stories from drivers or carriers. Our program is not perfect, but I think we’re very very fair and we do look at every single challenge. … We’ve encouraged other states to do it as well.”

Next in this series: Results of the Minnesota fatigue checklist blowback

Find all of the CSA’s Data Trail state profiles via the links below: