California ports are a battleground over predatory truck lease-purchase programs, which have helped prompt union organizing efforts and pushback from labor and the state. Photo | Courtesy of Port of Long Beach

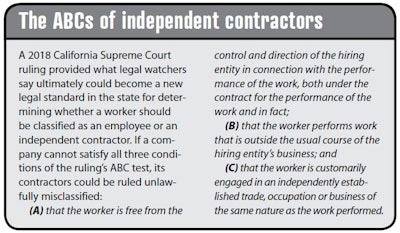

California ports are a battleground over predatory truck lease-purchase programs, which have helped prompt union organizing efforts and pushback from labor and the state. Photo | Courtesy of Port of Long BeachThe independent contractor classification last year took what some see as an uppercut to the chin in the California high court case of Dynamex v. Superior Court of Los Angeles. The court used what’s commonly known as the “ABC test” to make the determination that light- and medium-duty local delivery contractors for Dynamex had been misclassified as independent contractors. They’d been converted from W-2 employees a decade earlier.

The test could have far-reaching consequences because, applied elsewhere, it could change how the Internal Revenue Service and state tax and labor departments look at self-employed owner-operators leased to carriers. Depending on how subsequent judicial and legislative actions play out, it could become much more difficult to find work as an independent-contractor trucker in California, especially in port applications, and perhaps elsewhere.

Under the ABC test, three conditions must be met to properly classify independent contractors. For trucking, it’s part B that’s most problematic, requiring an independent contractor to be in a field of work outside the usual course of the carrier’s business.

Applied broadly, any trucking entity that employs drivers in company trucks but also maintains a division of independent contractors could be open to legal action for misclassifying its owner-operators. As in cases such as Dynamex, they could be subject to employee-focused wage and hour rules.

California labor laws require that employers provide a 30-minute meal break every five hours at work and a paid 15-minute rest break for every four hours of work time.

Few trucking companies before recent history have bothered with such regulations, given the nature of the business. However, “every state has them” in some form, says Todd Spencer, president of the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association.

Apart from evolving interpretations of break requirements, the owner-operator model in California has been undermined from within by lease-purchase-type arrangements abused by bad actors, particularly in port operations. USA Today’s “Rigged” series exposed dramatic examples where ostensibly independent truckers essentially become indentured servants, dependent on the carrier to make increasingly unaffordable lease payments. In many cases, they never fully take ownership of the truck. In the worst cases, they end up making little to no income.

These abuses, particularly in the busy Los Angeles and Long Beach ports, have provided a beachhead for union organizers. Increasingly, drivers with union support or not have targeted carriers with class-action lawsuits seeking misclassification judgments and, then, back pay for newly reclassified employee drivers denied breaks required by California law.

Such suits don’t always follow that exact blueprint, as small fleet AB Trucking’s story in Oakland, part of this series, makes clear, but they’ve proven increasingly successful since a 2014 federal court ruling established the precedent that California law on breaks applies to employee drivers. Among the most recent awards, with the carrier signaling intent to appeal, the California Labor Commissioner sent nearly $6 million to 24 drivers who sued their carriers claiming they were misclassified as contractors.

For a motor carrier, as with some other businesses, two attractions of the independent contractor status are simplicity and costs — avoiding unemployment-insurance responsibilities and in most cases placing the burdens of tax payment and workers compensation onto the “self-employed” worker. Many of the administrative responsibilities of employment are avoided, including meal and rest breaks.

For the contractor, shouldering those burdens is tolerable because, ideally, the relationship enhances earning potential and operational freedom. Yet for too many that hasn’t been the case.

With interstate company drivers long exempted from federal overtime-pay requirements, and with the hours of service rule at odds with state break requirements, trucking has evolved in a bad way, Spencer contends. “We have too many people that long ago quit placing any value whatsoever on a driver’s time,” he says. Carriers that “grumble” about the state meal and rest breaks situation, he feels, just “don’t want to pay [drivers] for that time.”

In the wake of related lawsuits out West, there were moves to get Congress – and when that failed, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration – to settle the matter by declaring federal pre-emption of meal and rest break regulations. Those efforts were led by the American Trucking Associations and smaller carrier groups such as the Western States Trucking Association.

In December, FMCSA issued a declaration that California meal and rest breaks are pre-empted under federal law and that carriers and drivers need not comply with them. Less than a week later, the Teamsters union challenged the agency’s action in court. Some watchers believe the legal wrangling could send the issue to the U.S. Supreme Court.

For now, it remains the case for motor carriers based in California or employing state-based drivers that putting compensatory value on all work tasks other than just driving is the best defense against misclassification and meal-and-rest-breaks litigation, says attorney Greg Feary.

“If you can work through a way in which to compensate independent contractors so that the enterprising plaintiff’s attorney doesn’t see a reason to sue, that’s how you limit your risk,” says Feary, of the Scopelitus Garvin Light Hanson & Feary firm. A “big issue is California is there is no wage averaging — plaintiffs’ attorneys make an argument that if the truck’s not moving, and the driver’s being paid on the basis of it moving, they’re not getting paid at all” for times when it’s not. “They’re not making minimum wage” for that time because it’s not directly compensated.

Spencer acknowledges the Teamsters’ role in leading some of the litigation that’s occurred. He takes Feary’s advice further: “The best play on organized labor is to treat your folks right, to pay them well,” he says. Trucker income 30 to 40 years ago “was significantly higher overall than what it is now,” in part due to organized labor’s presence. “We’ve been moving in the wrong direction for a long time.”

From a very-small-fleet perspective, the leased-owner-operator model with percentage pay reflects the value of the relationship between the carrier and the leased owner-operator and avoids the unpaid time issue, contends owner-operator Darril Lightburn. Based in Southern California and one of two operators leased to small-fleet owner-operator Jimmy Nevarez’ Angus Transportation, Lightburn says he is paid as a contractor a negotiated lump sum for each move he makes.

“You’re making money” according to the entire move, he adds, “and the carrier’s making money — that creates more than a win-win for a contractor.” Perhaps that also makes it unlikely an attorney can make the successful argument of uncompensated time that Feary highlights.

Lightburn’s a negotiator in the arrangement, too, just like Nevarez is with the mostly regular brokers he taps for freight. Nevarez “doesn’t call me and say, ‘This is where you’re going,’ ” Lightburn says. “We negotiate with each other.”

Following Nevarez getting his authority with one truck specializing in rail intermodal containers – well away from the ports – Angus now runs dry freight in food-grade vans. He knows that developments in California courts could put the leasing arrangement he has with Lightburn in jeopardy, even with it being as traditionally entrepreneurial as it is.

In the wake of the Dynamex ruling using the ABC test, the California Chamber of Commerce put together the “I’m Independent” coalition of businesses that view the test as an assault on the contractor model. The coalition staged an outreach to lawmakers in Sacramento last summer.

The coalition “will look to support legislation that clarifies and reforms the test set forth in Dynamex so that individuals who choose and want to be freelancers can still do so,” says Denise Davis of the chamber.

The SoCal-based Western States Trucking Association is a member. WSTA representative and former owner-operator Joe Rajkovacz notes two bills were introduced in the State Legislature in the wake of the Dynamex ruling. One would cut against use of the ABC test; the other would do the opposite.

WSTA, too, “filed a federal lawsuit against applying the ABC test to the trucking industry,” Rajkovacz says, supporting the argument that the Federal Aviation Administration Authorization Act pre-empts application of the test. “We do have some precedent in a case out of Massachusetts.” It found the test’s problematic B prong could not be applied in a particular delivery-service contractors-related case, citing FAAAA.

The California Trucking Association also filed suit over the Dynamex ruling in federal court. Feary speculates neither suit will see action until late this year.

Feary also notes another case, where a federal court in November considered the application of the ABC test to a group of port drayage drivers contracted to XPO. Feary contends the court in that case essentially said applying the ABC test itself to the contractors was in violation of FAAAA’s prohibition on any state law that impacts the “prices, routes and services of a motor carrier.”

For that single case, the court fell back on the more in-depth, multifactor “Borello test.” The single ruling in the XPO case is not precedent-setting. Only if it or another of the lawsuits around federal pre-emption were to reach the appeals stage, and be decided on, would precedent against use of the ABC test be set.

If the screws continue to tighten on the independent contractor status in California and beyond, the future for the approach to leasing owner-operators could tack toward an employment arrangement. Or more likely, it would go in the opposite direction: securing operating authority for most who value their independence.

Rajkovacz has been in discussions with three owner-operator-heavy carriers in California about that potential work-around. Operating as a full-fledged motor carrier, the owner-operator would have contractual agreements with motor carriers’ brokerage or freight-forwarder arms.

“Most of these guys have been the targets of Teamster-inspired lawsuits,” he says, and “wouldn’t ever want to be on a radar that they’re engaging us.” They nonetheless believe “this is unfortunately a necessary step until there’s an outcome from the lawsuits.”

The Teamsters challenge to FMCSA’s pre-Christmas assertion of federal pre-emption of California’s break rules will be decided in the same Ninth Circuit federal appeals court that in 2014 established the meal and rest breaks precedent for employee drivers.

OOIDA hopes to elevate the conversation around the issues to the national stage with the new Congress. They see Rep. Peter DeFazio of Oregon, the Democrat assuming leadership of the House Transportation Committee, as more attuned to trucking and truckers. “I think there will be opportunities to talk about all of this in congressional hearings this year,” Spencer says.

In January, too, the Supreme Court issued a ruling in a lease-purchase driver’s case against Prime that could eventuate in more misclassification suits seeing the light of day in court, rather than being forced into private arbitration.

Spencer adds that leased-to-independent conversions could be viable for businesses that feel threatened by the ABC test. He pointed also to operations in which owner-operators lease their equipment to carriers that pay them as W-2 employees, citing a Seattle-based small-carrier member with employee owner-operators. The owner handles compensation by separating a percentage for employee driver pay and another percentage to pay for equipment use.

Spencer views California, especially with its predatory lease-purchase-type arrangements, as something of a ground zero for changing dynamics harmful to owner-operators. “What goes on in California is probably some of the most dramatic examples of where independent contractor relationships are basically used and abused.”

It’s easy to see, he adds, “the detrimental effects it’s had through the years, in terms of basically undermining the future viability of small-business truckers. It lowers the floor for everyone.”

Next in this series: ‘Employee’ owner-operators? Not many trucking today have experienced such an arrangement