Previous piece in this feature package: Drivers citing coercion face an uphill battle

Shippers and receivers can be found guilty of driver coercion in certain circumstances of excessive detention or pressuring a driver to log personal conveyance.

Shippers and receivers can be found guilty of driver coercion in certain circumstances of excessive detention or pressuring a driver to log personal conveyance.One standout aspect of the coercion rule is that it marked the first time the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration gained some authority to investigate and fine shippers and receivers not already under the purview of its regulation. The rule also broadened agency authorities over brokers. It now has the ability to hold all these parties accountable for forcing drivers to violate hours of service and other regulations.

Ray Martinez, making his first public tour through the world of truckers in his short tenure as FMCSA administrator, heard at least one anecdote of such driver abuse at the March 2018 Mid-America Trucking Show in Louisville, Kentucky. During an agency listening session, a small-fleet owner told how one of his drivers, nearly out of hours, was detained at a facility for six hours. This happened after carrier personnel talked with the facility and the broker on the load to “make sure that if the driver sat for more than two hours, he’d have a safe place to park,” the fleet owner said. That “safe place” to park and regain hours never materialized.

“Shippers need to be held to the fire and not pay just $25 an hour for detention” and think the problem goes away, the fleet owner said.

FMCSA Office of Enforcement and Compliance Director Joe DeLorenzo responded that the coercion rule “for the first time gave us enforcement authority over a shipper [or receiver] that causes a violation of the regs” by a driver.

This six-feature package examines outcomes over the four years the FMCSA’s coercion rule has been in place. See navigation options at the bottom of the story to examine the remainder of the reporting. Access a list of all the stories via this link.

This six-feature package examines outcomes over the four years the FMCSA’s coercion rule has been in place. See navigation options at the bottom of the story to examine the remainder of the reporting. Access a list of all the stories via this link.Inability to address such problems “within the existing regulations,” DeLorenzo said, led to development of the coercion rule. Now, when such problems come to light, “we can go after them investigatively and fine them for that.”

With the electronic logging device mandate and yard moves functionality, FMCSA addressed sticky situations of short truck moves around shippers/receivers, truck stops and similar situations. Two months after the discussion at MATS, the agency also changed its guidance regarding the off-duty driving status of personal conveyance, too. FMCSA allowed PC use to move to the nearest safe parking location from a shipper or receiver after load/unload exhausts hours availability.

Yet this shipper/receiver scenario isn’t the only coercive practice by entities other than carriers, in the view of owner-operators.

For instance: withholding payment or threatening to do so if a trucker refuses to violate regulations for the sake of delivering on time. One operator commenting under an Overdrive story prior to the change in the PC guidance recalled being escorted by police out of a shipper facility when he refused to violate hours after a lengthy delay. The shipper then “banned me and is refusing to pay for the four pallets that they took seven hours to unload.”

If a shipper, receiver or broker retaliates in such fashion after knowing its demands will put you in violation, under the coercion rule their action merits a formal complaint as much as a carrier’s action would.

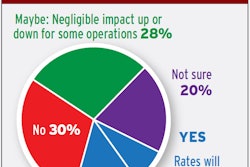

Virtually all coercion complaints the agency has received have been about carriers, DeLorenzo says. A look at the 18,000-plus enforcement cases closed since the beginning of 2016, most not related to coercion, shows 10 cases having been concluded with a fine issued to one or another non-hazmat shipper entity by the agency, and no cases against brokers concluded.

In all the closed cases against shippers, violations involved resembled those in cases closed against carriers; the investigated shipper entities clearly also own trucks and employ drivers.

All those shippers also had U.S. Department of Transportation numbers, though DeLorenzo emphasizes that coercion enforcement is not contingent on a business “possessing a USDOT number or FMCSA operating authority.”

Lewie Pugh, executive vice president of the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association, questions the validity of FMCSA’s authority to investigate such entities other than those previously under agency purview. “FMCSA has no real direct oversight of shippers and receivers,” he says. Pugh suggests a public list of shippers and receivers that have violated the rule or been investigated would be helpful.

“If you’re a carrier and you have a shipper/receiver who’s jacking with your drivers,” Pugh adds, “you need to charge that shipper [detention] and pay it direct to the driver. If a shipper or receiver tells your driver to take his break” while in readiness to unload or load, “they can’t do that. Drivers should take that to the carrier.”

Pugh and some others believe that if enough people engage FMCSA over such problems, shippers and receivers with the biggest problems might feel more impetus to fix their dockside problems. “If FMCSA mailboxes get filled up with Walmarts and Piggly Wigglys, somebody in the government might do something,” Pugh says.

Another approach is to turn the tables on applying force, as driver Bob Stanton has it: “I have a very simple technique on the very rare occasions I get pressure” to violate regs, he says. “I simply ask, ‘How do you spell your last name? I want to get it right in the National Consumer Complaint Database complaint to FMCSA, and the email to our director of safety.”

Only once, he said, did the conversation progress to him saying: “Do you think you’ll be fired before or after the FMCSA starts the investigation of the complaint?”

Read next: Righteous whistleblower or 'disgruntled employee'?

Also in this package:

Cracks in the system: Blowing the whistle on coercion

The irony of e-logging and coercion: Complaints on a steady rise since mandate

Drivers citing coercion face an uphill battle

Parties other than carriers now subject to enforcement under the coercion rule