Previously in this series: ‘I will take your daughters’: Abusive business lenders under increasing scrutiny from FTC

When Heather Wilson and her husband, co-owners of five-truck Dream Trucking in Hampstead, Maryland, started taking out tens of thousands of dollars in merchant cash advances, they didn’t realize the risks they had taken.

Access a brief video explaining merchant cash advance lending and how to avoid bad terms via the first installment in Part 3 of this series.

Access a brief video explaining merchant cash advance lending and how to avoid bad terms via the first installment in Part 3 of this series. “We’ve lost our house and cars,” said Heather Wilson. They’ve moved from a 3,000-square-foot home into a 1,000-square-foot home. Two cars were repossessed.

One of the MCA providers froze their bank account. They’ve since opened another, allowing her husband and four other drivers to keep Dream Trucking alive.

An MCA provides a lump sum to a small business in return for a share of future receivables. The payments are usually auto-drafted nightly from the borrower’s bank account. The initial terms, plus fees and default penalties, can easily send the effective annual percentage rate into triple digits.

What the Wilsons and other small fleets often don’t notice or understand is that their MCA contract might contain a legal provision called confession of judgment. A borrower signing a COJ waives the right to due process, effectively giving the lender a green light to collect money and other pledged assets if the borrower defaults in the slightest way. Because there’s no requirement to notify the borrower a COJ filing is coming, a frozen or emptied bank account often seriously disrupts basic operations, such as meeting payroll.

“If your trucking company doesn’t pay, they don’t have to file lawsuits” to repossess your property, said Kevin McCarthy, whose Arizona law firm renegotiates lower payments for debtors in crisis, including truck fleets. With your bank account, “they can sweep the account without any notice to the borrower.”

Heather Wilson said she didn’t understand the extent to which she put assets at risk to obtain two of the MCAs, which contained COJs. Otherwise, “I would have never signed anything,” she said. “I remember telling one of them I didn’t want my house involved. They said, ‘We understand, we wouldn’t want our house involved either.’ They just lie to you.”

What a COJ acts upon is the uniform commercial code filing that’s part of virtually every MCA application. UCC filings, made at the state level, are liens that a creditor uses to establish that it has an interest in a debtor’s business or personal property that was pledged to secure financing.

“In most cases, lenders will require a personal guarantee, which means that the borrower is also securing the loan with their personal assets,” said Seth Nelson, who oversees SBA loans for Fundera, an online business loan marketplace that matches applicants with lenders.

UCC filings over the last five years show that 9,400 businesses with U.S. DOT numbers had 12,000 UCCs tied to loans that appear to be MCAs, though some could be other types of loans. These entities would be trucking fleets and owner-operators with authority principally, but also freight brokers, freight forwarders, motor coach companies and others. The filings were gathered by RigDig, a trucking industry data subsidiary of Overdrive’s publisher, Randall-Reilly.

The UCC lien often covers all of a company’s receivables, said attorney Shane Heskin in testimony a year ago to the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Small Business about MCA abuses.

“As a result, upon any alleged default by the small business owner, the MCA company has a wide range of ways to cripple a business and thereby extort a settlement under duress,” Heskin said. “Credit card processors and PayPal accounts are usually the first to get hit. If that does not work, the MCA company can use the merchant’s bank statements to identify their customers. That, of course, can have a domino effect because not only does it freeze-up desperately needed funds, but more importantly, it also threatens the relationship with the customer.”

COJs came into widespread use in the last decade and have become a staple of contracts offered by the less reputable MCA providers. Nelson called COJs “a stain on the lending industry.” He said Fundera excludes from its roster of lenders those requiring COJs.

Because they target business clients, MCAs dodge the consumer protections of the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act. And because the MCAs are a form of factoring – technically not a loan, as some providers argue – they avoid usury laws, which vary by state.

The abuses allowed by COJs, particularly in MCA contracts, have come under heavy scrutiny. A major development came in 2019 when New York, once known for rubber-stamping COJ filings from around the country, outlawed COJs for borrowers based outside of the state.

In a 2018 investigative series about COJs and MCAs, “Sign here to lose everything,” Bloomberg Businessweek reported that COJs date in some form to the Middle Ages. However, “some U.S. states outlawed confessions in the middle of the 20th century, and federal regulators banned them for consumer loans in 1985.”

Bloomberg traces their modern use to 2009, when David Glass and a friend launched Yellowstone Capital, then filed the industry’s first COJ in 2012. “Among the hustlers and con men who work the bottom rungs of Wall Street, Glass is a legend,” wrote Bloomberg. “Before he was 30, he’d inspired the 2000 stock-scam movie ‘Boiler Room’ and was “later busted by the FBI for insider trading.”

The following video clip shows David Glass cursing and yelling as he fires an employee in front of co-workers. Glass co-founded Yellowstone Capital, which pioneered the use of confessions of judgment in the merchant cash advance niche.

Because COJs couldn’t be enforced in certain states, Yellowstone and other MCA providers started adding contract provisions to allow COJ filing in New York, which accepted them from any state. As a result, “these lenders have co-opted New York’s court system and turned it into a high-speed debt-collection machine. Government officials enable the whole scheme,” Bloomberg reported, estimating that a fourth of the cases came from Yellowstone.

Yellowstone and Green Capital have been reorganized and rebranded as subsidiaries of Fundry. Fundry did not respond to an interview request from Overdrive.

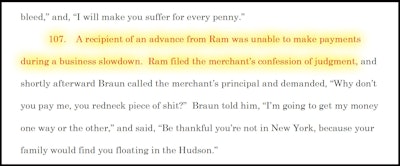

One of the examples of abuse cited in the lawsuit filed by the state of New York involves an incident with an MCA client from Ram Capital, one of the defendants. Braun is Jonathan Braun, also a defendant. Click through the image for a larger view.

One of the examples of abuse cited in the lawsuit filed by the state of New York involves an incident with an MCA client from Ram Capital, one of the defendants. Braun is Jonathan Braun, also a defendant. Click through the image for a larger view.It was Bloomberg’s series that led to an investigation by the state, said New York Attorney General Letitia James in a statement about a lawsuit her office filed this month against three related companies engaged in MCAs. The three are not tied to Fundry or Yellowstone.

The lawsuit alleges extravagant interest rates and fees charged, as well as deceptive practices, and also focuses on COJs. The attorney general’s statement said the confessions were required in MCAs provided by the defendants: RCG Advances, LLC (formerly known as Richmond Capital Group, LLC, and also doing business as Viceroy Capital Funding and Ram Capital Funding); Ram Capital Funding LLC; and four individuals.

Their COJ filings involved “no notice to the merchant, no review by judges, and no other evidence apart from the Richmond companies’ own affidavits,” said James’s statement. “With New York court judgments in hand, the Richmond companies would then quickly seize money from merchants’ bank accounts. The lawsuit contends that the Richmond companies applied these tactics to obtain judgments against more than 400 merchants.”

Overdrive was unable to reach the three companies by phone or email.

Now that New York no longer processes the out-of-state COJs, lenders have moved those filings to Utah and Pennsylvania, said Heskin, a Philadelphia-based attorney who represents clients claiming harm from COJ enforcement and extremely high MCA payments.

Heskin said of the 100-plus MCA clients he’s represented, six to 10 are trucking companies. When they take MCAs, “they generally end up going out of business,” he said.

Though MCA providers mostly do business with small businesses, Heskin said some of his fleet clients have had annual revenues between $10 million and $100 million.

MCA providers will sometimes negotiate a lower amount for a client who can pay the entire sum at once, he said. “But if you can’t do that – and most people cannot do that – the option is to negotiate a longer-term payout.”

While the COJ puts all business assets at risk in the event of default, the right to go after personal assets varies by state, Heskin said. “There are some that will actually put a mortgage on your home.”

Because the “confession process is seamless and swift” and the client often isn’t even aware of it until learning bank accounts are frozen, problems can go beyond failure to meet routine financial obligations, Heskin said in his congressional testimony. “The MCA company gains incredible leverage over the merchant such that the merchant is forced to capitulate to the MCA company’s demands, close its doors or file for bankruptcy just to stave off the aggressive collection tactics employed by certain MCA companies.”

One common tactic is to pressure debtors to take out additional MCAs to make ends meet. The offers often come from MCA providers new to the borrower. Many borrowers find no easy escape once they are “stacked” with MCAs, as interest, fees and penalties compound.

Heskin’s testimony indicated the repercussions of COJ filings can be even more unfair in that some are done fraudulently or with no regard for mitigating circumstances. Giving examples from his clients and other research, he noted these practices: forging documents; falsely claiming a client had blocked its bank account to stop remitting payments; filing COJs against merchants based in a state where COJs are illegal; and filing against a merchant who defaulted during an evacuation due to Hurricane Matthew; and another who was on a cruise when a customer’s bounced check triggered a default.

A common form of fraud, which can open the door to a COJ filing, is when the MCA provider fails to lower the borrower’s monthly payment in proportion to a drop in revenue, Heskin said. “Clients need to read their contracts and understand that if they are going through financial difficulties [they need] to utilize their right to reconciliation” by asking for a refund, he said. “It’s usually in the fine print.”

Have you had bad experiences with a merchant cash advance? Comment below or write [email protected]. Access all installments in the ‘Cash Flow Crisis’ series via the following link to the first part: