Previously in this series: How load factoring companies’ diverse services help some fleets grow

When Chris Fann received a $150,000 cash advance to rent 10 Penske trucks, he repaid the money in six to eight months, then borrowed from a different lender to get 10 more trucks. By 2017, he was leasing 24 Penske trucks.

“When the rates started to fall I needed some extra money to get me through what I thought was a rough patch, so I took another loan,” from a third party, wrote Fann. His all-owner-operator fleet based in South Texas, C. Fann Transportation, serves the lower 48 states, Mexico and Canada.

The next installment in Part 3 will examine how the Federal Trade Commission is increasing its scrutiny of MCA lending.

The next installment in Part 3 will examine how the Federal Trade Commission is increasing its scrutiny of MCA lending.His rough patch was about to get bumpier. One finance company after another “stacked” him with merchant cash advances. Some were dubbed a “bridge loan” or “reverse consolidation loan,” each supposedly geared to help pay off earlier advances. There were promises of $500,000 and $1 million loans that never materialized.

But enough did come through to send the auto-drafts from his bank account through the roof. At one point, “$64,345 a week is coming out in MCA loans,” he said.

Small-fleet owner Chris Fann was “hemorrhaging money” last winter, he said, as business slowed down and his merchant cash advance payments exceeded $64,000 a week.

Small-fleet owner Chris Fann was “hemorrhaging money” last winter, he said, as business slowed down and his merchant cash advance payments exceeded $64,000 a week.An MCA provides cash to a business that needs money immediately and lacks the credit to obtain a traditional loan with better terms. The advance is set up to be repaid with a guaranteed share of receivables, often over six to 12 months, which sometimes works out. Too often is doesn’t, as when a single default triggers a spiral of increasing debt that becomes unmanageable, threatening the life of the business and sometimes stripping the owner of assets.

“It has been a horrible fight for the last eight months trying to fight off all the MCAs as I am now eight deep and going broke trying to pay everyone while rates are still dropping,” Fann wrote April 24. By mid-May, he’d lost the Penske trucks and relied on 12 owner-operators to keep his business going. His total debt was about $300,000.

Fann Transportation is hardly alone among small fleets. Data from RigDig, a trucking industry data service, shows that thousands of fleets and other trucking-related businesses have taken MCAs in the last five years.

Long before the coronavirus shut down much of the economy, MCA providers were attracting small fleets and other small businesses desperate to make ends meet or, more ambitiously, looking to fund an expansion.

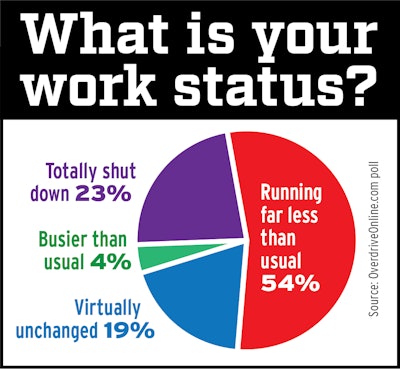

A large majority of Overdrive readers have suffered major financial setbacks due to economic contraction related to the coronavirus. These results come from a May 28 through June 9 survey of Overdrive readers, most having their own operating authority.

A large majority of Overdrive readers have suffered major financial setbacks due to economic contraction related to the coronavirus. These results come from a May 28 through June 9 survey of Overdrive readers, most having their own operating authority.The financial status of small fleets worsened considerably this spring. In a recent COVID 19-related survey of Overdrive readers, three in four respondents rated their status as “totally shut down” or “running far less than usual.” Most respondents were owner-operators with their own authority, including fleets with fewer than 10 trucks.

Many of these independents had little or no cash reserve before the pandemic, and many serve niches where freight has dried up, sending rates into the toilet. With so many operators struggling, opportunities have been ripe for aggressive finance companies to prey on those lacking the financial savvy to recognize potentially harmful deals.

“There can be horror stories,” said Brock Blake, CEO of Lendio, an online small-business loan marketplace that matches clients, including small fleets, with MCA providers and other lenders. The horror stories include clients who lose their business and personal assets, and who see bank accounts frozen or their funds withdrawn by the MCA provider, without notice.

Such outcomes are especially true if the provider isn’t “totally transparent about what the rates and terms are,” Blake said, “or the borrower didn’t understand the dynamics of it.”

The business model used by some unscrupulous MCA providers is “predatory,” said Jennifer Licktieg, president of TBS Factoring Service. “We’ve analyzed a lot of MCA agreements. There’s lots of problems with them.”

So what’s attractive about them? Within a day or two of receiving a brief application, MCA providers will fund clients that other lenders would reject. “They just threw money at me,” Fann recalled.

Little qualifying information is required other than recent bank statements, used to determine potential payback from future receivables. Another part of the MCA pitch: that the percentage of receivables arrangement keeps repayment affordable – if business gets slow, you pay less.

For a quick summary of how merchant cash advance providers can take advantage of small fleets, watch the two-minute video above.

For a quick summary of how merchant cash advance providers can take advantage of small fleets, watch the two-minute video above.Typical customers are retailers, with repayment set as a cut of each day’s credit card receipts. Businesses getting little or no income from credit cards, such as a small fleet, usually agree to an automated bank draft. For a small fleet that doesn’t receive income daily, a minimum daily withdrawal might be required.

Commercial Fleet Financing owner Matt Manero said he’d seen MCA daily withdrawals on customers’ bank statements. He said in February that average customer credit scores had dropped from 2019 levels, reflecting a higher share of his customers accepting MCA deals.

“It’s a high-interest loan with a very short term,” he said. “It’s becoming very negative in our industry.”

Commercial Fleet sees examples where a customer lacked cash for a down payment on a used truck, then received an email or other solicitation for an unsecured loan of, say, $50,000, deposited within 24 hours, Manero said. Acting upon that, the customer would end up with two loans for the truck: 80% of the purchase price from the finance company, 20% from the MCA. That was often more than could be reasonably afforded, often leading to the borrower getting stacked further with MCAs.

Fann began his descent when, after his third loan, “the dip did not bounce back,” he wrote. Then “a super-unscrupulous company” approached him with “a bridge loan with simple equity and a $500,000 letter of intent to finance. Now they stacked me 3 deep and did not come through with the $500,000. So I was starting to feel the pressure of the daily/weekly payments.”

Not all MCA customers wind up in a death spiral of high interest, penalties and other fees. There are situations where an MCA indeed helps the customer, say Manero and others, just as Fann succeeded with the expansions funded by his first two MCAs. Others aren’t so fortunate.

The owner of a four-truck fleet based in the Northeast says the MCA providers that stacked him with three cash advances were “not bad” to work with, but he got behind on the daily payments. So when he was contacted by MCA provider Global Funding Experts about consolidating the loans, he agreed to a plan. GFE charged him about $1,000 a week, reflecting an extremely high default interest rate, he said, and his rep with the company has been verbally abusive when the owner tries to explain temporary setbacks. Now dealing with a different GFE rep, the owner resumed making weekly $300 payments.

The owner, who’s considering getting a lawyer to contest the arrangement, declined to speak for attribution because he feels it would harm his legal position. He said he’s already repaid double the amount he borrowed, though GFE contends he owes more because of interest and fees.

GFE did not respond to requests for an interview.

Hundreds of clients in situations like this, including small fleets, work with McCarthy Law PLC of Scottsdale, Arizona, each year to negotiate lower debts with creditors. Many have exhausted their credit through business or personal credit cards, personal loans, second mortgages, and business lines of credit, said principal Kevin McCarthy.

Negotiations vary widely, he said, but he aims for reducing the debt to 40% of its current level, and charging 20% for his fee. At those levels, a client owing $100,000 would end up paying $60,000.

Of clients with MCA debt, “we see on average three MCAs per client, but sometimes more,” he said. “Once the MCAs are stacked, your cash-flow is spread so thin that any minor disruption – a late payment, a big repair bill, a pandemic – can cause the whole house of cards to fall.”

Not only are some MCA providers eager to stack new cash advances on their clients, some “have payment terms that were impossible for the borrower to meet even when they took the loan,” McCarthy said of 54 MCA providers listed on his firm’s website. Certain providers “also don’t do much in the way of working with borrowers when they are in a tight spot.”

MCA agreements sometimes state effective annual percentage rates – the APR figure that’s commonly used with credit cards and elsewhere. It’s often stated as around 20% or 25%, McCarthy said.

Instead of being structured around an APR, MCAs instead use a factor rate. It’s “calculated as the payback amount over the actual loan amount,” explained Seth Nelson, who manages U.S. Small Business Administration lending for the online business loan marketplace Fundera.

If you accept a $100,000 MCA at a factor of 1.49, you’re agreeing to pay back $149,000. The agreement also specifies the percentage of receipts you pay daily to the provider, say 10%, he said. Since precise future receivable amounts are unknown, it’s also unknown exactly how long it will take to pay $149,000, and therefore exactly what the final APR will be.

Such terms are already expensive, but a borrower’s situation can get worse, largely because of default fees, which often are not prominently disclosed in the contract. “That’s where the money really gets big,” McCarthy said.

“The very first time those funds are not available, those interest and fees escalate,” said TBS Factoring’s Licktieg. Counting higher rates and penalties, prolonged repayment, and often multiple MCAs taken out to consolidate debt, costs soar, often sending the effective APR far above 100%.

Such costs are a big way that the factoring practiced by MCAs differs from companies that have traditionally factored current receivables for fleets. With reputable factors serving the trucking industry, “the risk is taken by the factor,” not the client, said Licktieg. This is true in non-recourse factoring, the most common arrangement, where the client gets paid even if the factor doesn’t collect the money owed. In recourse factoring, the fleet is responsible for paying the factoring company back if it is able to collect; the factor takes a smaller piece of the invoice, generally.

When a small-fleet client saddled with unworkable MCA debt comes to TBS, a typical solution is “we have to buy out the balance of the MCA plus establish a factoring plan,” Licktieg said. “We set it up so that however long it’s going to take to send the invoices into us, we can hold back funds to pay back the MCA or, in this case, pay back ourselves for paying the MCA.”

Records of creditor filings with states show that thousands of trucking-related entities have obtained merchant cash advances. The uniform commercial code filings are liens that a creditor files to establish that it has an interest in a debtor’s personal or business property that was pledged to secure financing.

States’ records of UCC filings over the last five years show that 9,400 businesses with U.S. DOT numbers had 12,000 UCCs tied to loans that appear to be MCAs, though some could be other types of loans. These entities would be trucking fleets and owner-operators with authority principally, but also freight brokers, freight forwarders, motor coach companies and others.

The records reflect filings from Jan. 1, 2015 through Dec. 5, 2019. They were gathered by RigDig, a data subsidiary of Overdrive’s publisher, Randall-Reilly.

Have you had bad experiences with a merchant cash advance? Comment below or write [email protected].