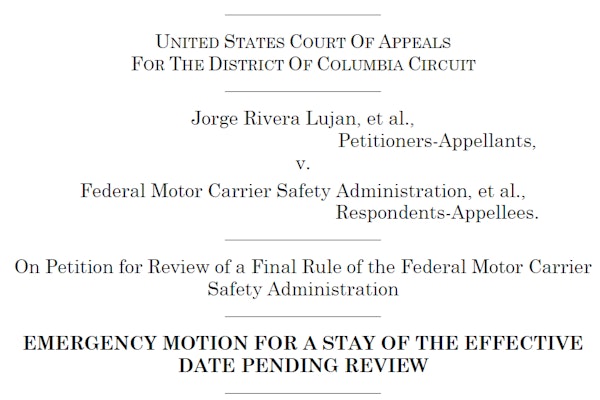

Presenting today at the MCSAC meeting on DOT-wide systematic regulatory review in advance of discussion of FMCSA’s Section 610 regulatory impact analysis agenda for small businesses, FMCSA’s Neil Eisner, “Mr. Regulation” as MCSAC’s Shannon Watson has it, shared an anecdote that could hold any number of business lessons. He shared it with the intent of illustrating the complexity of the regulatory process, where agency staff must weigh safety benefits versus cost impact on small businesses in developing regulations.

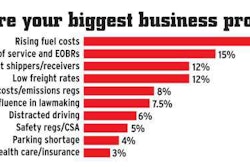

The MCSAC is being tasked today with providing recommendations on ways to more effectively engage the public — that’s you — in their rule-review processes, as well as provide guidance on several rules already in the routine review process.

At any rate, Eisner’s anecdote described a decades long process toward the Congressional mandate for airbags in passenger cars: “In the 1970s NHTSA required manual seatbelts” in new cars, he said, “but still 12,000 people were dying on the roads. They decided to look at it and see what they could do. They did risk assessments and cost-benefit analyses,” looking at a range of alternatives to fix the problems from “states making mandatory use laws” to looking around the world at various alternative solutions that had been taken: Educational campaigns happened to be one of those, as did using various “padding inside the car, air bags, and etc.”

All of this was happening during the Nixon administration to begin with, Eisner said. Conventional wisdom at the time held that in a high-impact crash it would be better to be thrown out of the vehicle rather than to remain in it. NHTSA tried a somewhat famous educational campaign that included television commercials showing what happened to a pumpkin that was thrown through the front windshield of a car in a high-speed crash. As Eisner recalled the commercial, its end showed a car bypassing the accident and smashing the pumpkin in the roadway.

Ultimately, Eisner said, “educational campaigns didn’t work,” mandatory-use laws didn’t work either. NHTSA “set up a rulemaking on automatic devices to mitigate frontal collision” injuries and deaths, i.e. airbags, etc., though they didn’t get so far as to require one kind of device or another. “There continued to be disputes on whether to do a demonstration program” during the Nixon administration, then the Carter administration, likewise “concerns over lttle issues — if the air container doesn’t have to be inflated [over the life of the vehicle], what happens when you have to crush these cars.”

The Carter administration put the rule in place, but the “Reagan administration decided to rescind the rule,” Eisner said, and after it ended up in court it ultimately came back to NHTSA, who said the rule would go in place “unless [a particular number of] states put in place a mandatory use law that specified a certain number of conditions.” They didn’t.

Once the rule was live, there was little movement in the on-highway stats or interest in air bag technology until two new Chrysler K cars collided at high speed in Northern Virginia, Eisner said, where the crash received national attention. The policeman interviewed on the news more or less said, “I arrived at the scene expecting to find two dead drivers,” but there were on further examination no occupants in either vehicle. “The drivers were walking around nearby, because they had air bags in their cars.”

Said Eisner, “That one accident — instead of pumpkins, live people in the cars — had more effect on individuals wanting safety features” than anything NHTSA had ever done around the issue. Congress eventually mandated air bags.