Eagle Express small fleet owner Leander Richmond got a bit of DataQs victory recently. Most of you know the DataQs system, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration protocol built to afford carriers, drivers and others a clear path toward challenging or simply correcting information collected about them.

Crash information, we’re talking, and inspections and their associated violations. In recent years, DataQs has also expanded in use and importance given it’s the venue for putting particular crashes up for review in the FMCSA’s program to make preventability determinations and potentially exclude them from CSA scoring. This year, the Crash Preventability Determination Program became permanent. Access a how-to when it comes to using DataQs to submit and manage requests for crash reviews via this link.

Richmond wasn’t submitting a crash. Rather, he was doing something a good bit more common — attempting to dispute a violation of the federal cell-phone-use statute that was marked on an inspection report by the state of Michigan after his driver had been pulled over at roadside and inspected.

No citation for cell-phone use was issued, and the driver was not utilizing the phone for anything other than GPS at the time of the stop, as the officer’s examination of the phone revealed. The federal definition for handheld device does not include utilizing the phone for GPS purposes, as Richmond pointed out, but rather handheld use while talking or texting, among other handheld uses.

Richmond’s first attempt to dispute the violation and potentially have it removed from his company’s and the driver’s record in CSA and Pre-Employment Screening Program systems was more than 8 months ago. His description of the initial effort is of a piece with the many horror stories around violations like this that I’ve heard through the years. Absent a citation to adjudicate in court — if successful there, carriers have a relatively simple way to get through the DataQs process successfully and have the violation removed — what owner-ops and other carriers come back to is often enough the department and/or the officer herself who marked the violation to begin with.

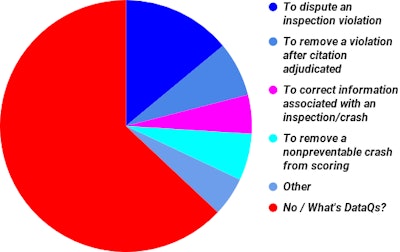

Note that, too, this kind of challenge to an inspection violation is the most common reason Overdrive readers are using the DataQs system:

Have you used the FMCSA’s DataQs violation/crash info-correction system?

Nearly half (47%) of respondents to November polling here at Overdrive hadn’t used the DataQs system at all, with another 16% reporting having no idea what it was. For those who had used it, represented by the various blue-tinged hues in the graph, the largest share reported DataQs use to challenge a violation (14%), irrespective of any citation adjudication.

Nearly half (47%) of respondents to November polling here at Overdrive hadn’t used the DataQs system at all, with another 16% reporting having no idea what it was. For those who had used it, represented by the various blue-tinged hues in the graph, the largest share reported DataQs use to challenge a violation (14%), irrespective of any citation adjudication.FMCSA points out that category of DataQs challenge also happens to be the least likely to result in an actual change in the information system underpinning the CSA and PSP programs. It’s also the most common form of DataQs challenge across all carriers. Of the 17,888 “incorrect violation” DataQs “requests for data review,” or RDRs (in FMCSA’s terminology), fielded in 2019, just around 39 percent were ultimately changed as a result. That might be interpreted as officers getting violations correct — after all, from an officer point of view, as more than one has pointed out to me, the best DataQs-success rate would be zero percent.

Yet I suspect that the low rate could also be illustrative of cases like Richmond’s, emblematic as it is of the chief criticism of the reviews program broadly. As he said, “The DataQ process failed miserably because the officers are not held to a standard other than what they believe. This was my experience when I argued with a sergeant on this same inspection report” some months back. Essentially, the issuing officer stood his ground on the violation, a Michigan State Police sergeant agreed, and the request for a change was denied.

How’d he eventually get it resolved?

A note delivered to the office of the Michigan Attorney General and copied to the state police included his reasoning, as summarized above, the language of the applicable federal statute, and among other things this note:

Not having an actual citation provides no mechanism by which this could have been handled through the court and I am not happy just accepting this as “the way it is.”

I would like to assert that mentioning the cell phone law, in the violations section, as a reason for this [stop] is as good as a guilty assessment in the CSA scoring process. If there was no violation in the stop then there should be no mention of a violation in the inspection report.

A lieutenant with the state police eventually agreed. “Another small victory,” Richmond said. Regular readers may recall another violation that Richmond was fighting in New Mexico, which I wrote about more than a year ago. It’s still in process, he said last week, with no resolution as yet.

There are states where DataQs appeals are handled outside the routine business of the issuing departments and jurisdictions, though they are few in number. There have been some in the advocacy community that see a role for a nationally focused review board of sorts to settle disputes about violation disputes like Richmond’s here.

We asked the question late last week — whether such a review panel, made up of industry and law enforcement reps and others as it’s most often envisioned, would be a useful development at this point. If you haven’t weighed in via the poll, do so below, and feel free to get in touch with me directly with your own stories — success tales or otherwise — of DataQs challenges.