Since the start of 2022, the Energy Information Administration's reported average price for a gallon of gasoline has climbed from $3.14 to $3.49, with the most common gas price in America right now at $2.99. Diesel, on the other hand, climbed over the same period from $3.61 to $5.31, or about a 38% jump while gasoline only moved a bit more than 10%.

But compared to gasoline, diesel is a less-refined product, and for decades, up until about 2004, it fetched a lower price. Outside of a few fleeting moments, diesel has been more expensive than gas ever since. GlobalPetrolPrices.com writes that gasoline costs more than diesel in 84% of the 161 countries it tracks, with diesel in most on average 9.8% cheaper. (Recent price swings may have moved those figures a bit.)

So why would a product that's easier to make, that's more vital to essential economic activities like construction, farming, and yes, trucking, sell at a premium to one that's harder to make? And why do four-wheelers seem to make out on the deal?

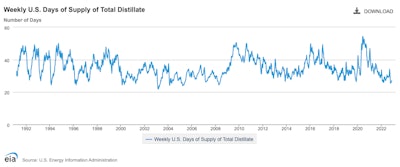

[Related: Only 25 days of diesel left? What to make of low inventories]

The EIA pins the answer on three main causes: Diesel demand has grown, transitioning to lower-sulfur diesels has impacted fuel production costs, and the federal excise tax for on-highway diesel sits at 24.3 cents per gallon while it's only 6 cents on gasoline.

But that sub-18 cent tax premium on diesel hardly explains the yawning chasm between the two prices in today's world, and ideally a free market would adapt to industry and demand changes to provide diesel at a lower cost.

Tom Kloza, the global head of energy analysis at Oil Price Information Service, said that the answer to expensive diesel starts with the barrel of crude oil itself.

Today, "diesel is the profitable part of the barrel," he said. "Gasoline is not a loss, but not very profitable. Throughout the world, diesel is the molecule that still has some support" in terms of pricing, "and for now, it's still a molecule in tight supply."

Diesel, as a fuel that uses a higher share of the overall barrel of crude, competes with jet fuel and other pricey petroleum products in a way that gasoline doesn't. "You can take the diesel molecule, crack it, and turn it into gasoline," Kloza said. However, "nobody has figured out yet how to make" gasoline into diesel.

As a thought experiment, Kloza walked through the example of a refinery taking in 100 barrels of crude. Under ordinary circumstances, the refinery would try to get maybe 50 barrels of gasoline, 30 of diesel, and about 10 of jet fuel alongside some other petroleum products.

[Related: Highly incentivized renewable diesel impacting supply of convention fuel]

These days, "every single refinery is trying to maximize the diesel cut" to maybe get 45 barrels of diesel and maybe 30 of gasoline, he said. "There's clearly motivation to make as much diesel as possible," with refiners making $50 or more on every barrel, and billions of barrels to sell. "This is unusual. There has been no other December in the history of this country or the world where diesel has fetched $50, $60, even $80 above crude," he said.

That's one reason diesel has risen so fast and remained so high: Everyone, from retailers to traders to governments, are worried about serious supply chain disruptions. Kloza said "very, very low stocks of diesel in the U.S. and E.U." saw the fuel of trucking trading so high above the price of crude, with worry soaring over a potentially cold winter and demand for heating oil, where diesel would become highly sought after because it doubles as a heating oil in much of the U.S. Northeast and Europe.

Russia's invasion of Ukraine has battered traders' outlook for natural gas and other heat sources, focusing a lot of attention on diesel at a time of historically low supply.

Since Overdrive last reported on the total estimated supply in U.S. reserves of distillate fuels, which includes diesel and heating oil, the then 25 days' worth of supply is now pegged at just over 27 days.

Since Overdrive last reported on the total estimated supply in U.S. reserves of distillate fuels, which includes diesel and heating oil, the then 25 days' worth of supply is now pegged at just over 27 days.

Kloza said traders typically look at the market 40 days ahead, so they're currently trying to estimate demand in January, when they expect gasoline demand will die down from holiday highs, but diesel demand could stay up. Oil traders speculating on higher futures can cause oil producers and retailers to hold onto their stock or raise prices in anticipation of greater worth.

Add to all of it the the possibility of a rail strike, which might hobble bulk hazmat movement. Kloza said DEF, not diesel itself, may find itself in trouble, and more likely it would harm gasoline prices rather than diesel, as ethanol, a critical component of popular E10 gas, wouldn't get its normal rail shipments.

[Related: Rail strike back on the table, this time for December]