Carriers are required to query drivers' records yearly in the FMCSA’s Drug and Alcohol Clearinghouse.

Carriers are required to query drivers' records yearly in the FMCSA’s Drug and Alcohol Clearinghouse.

The program took effect Jan. 6, 2020. All trucking companies with operating authority, even with only one truck, are required to register in the clearinghouse and to conduct a yearly query on each driver. The database is used by law enforcement, driver licensing agencies and carriers to check for driver violations.

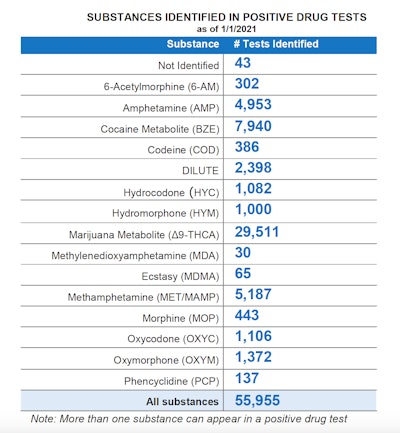

During this first year of the clearinghouse operation, more than 56,000 violations were recorded, only 1,203 of them alcohol-related.Of the 51,998 drivers who had at least one violation last year, 45,475 are still unable to drive. Of those, 34,769 have not even begun the return-to-work protocol of substance abuse counseling and testing negative for drugs and alcohol. Only 6,513 violators have completed it and are cleared to drive.

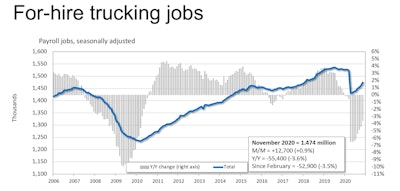

The 45,475 violators who aren’t cleared for commercial driving represent 1.3% of an estimated 3.6 million truck drivers in the United States, or 3.1% of the for-hire trucking employment total, almost 1.5 million, which includes non-driving jobs.

The impact of the clearinghouse has “culled another 40,000 or so drivers directly from the market, and probably thousands more have exited because they think they might not pass a drug test,” said analyst Avery Vise, discussing driver pool worries during a recent FTR webinar on the 2021 outlook.

Trucking employment is recovering quickly after plunging during the first weeks of the pandemic, but still has rebounded only to the level of early 2018, as shown in this chart from trucking consultant FTR. Among factors limiting fleets’ ability to ramp up capacity is constraints on the driver pool, which include increased access to drug testing results through the clearinghouse, FTR says.

Trucking employment is recovering quickly after plunging during the first weeks of the pandemic, but still has rebounded only to the level of early 2018, as shown in this chart from trucking consultant FTR. Among factors limiting fleets’ ability to ramp up capacity is constraints on the driver pool, which include increased access to drug testing results through the clearinghouse, FTR says.

Small-fleet drug testing has produced positives in about 1% of screens in recent years, said David Owen, president of the National Association of Small Trucking Companies. That data, comparable to industrywide rates, comes from 5,000 NASTC members that use the association’s testing service.

Because carriers are required to perform a clearinghouse query on all drivers annually, the initial deadline for testing all drivers was Jan. 5, which closed the system’s first 12-month period of operation. Carriers face a fine of up to $2,500 per offense if non-compliance surfaces in a compliance review or safety audit.

Among drug violations during 2020, by far the leading drug for positive tests was marijuana, with 29,511 violations. Cocaine and various amphetamines were next most common. Some drivers were charged with more than one violation.

Among drug violations during 2020, by far the leading drug for positive tests was marijuana, with 29,511 violations. Cocaine and various amphetamines were next most common. Some drivers were charged with more than one violation.

The required check is meant to ensure that drivers haven’t failed a drug or alcohol test, such as a pre-employment screen when applying for a job at another fleet, only to remain behind the wheel and employed at another fleet.

Enactment of the clearinghouse “did not change the federal drug and alcohol testing regulations or the required percentage of drivers tested,” said Duane DeBruyne, FMCSA spokesman. Also, “before the establishment of the clearinghouse, the identical number of drivers would still have been prohibited from operating. What’s different now is the degree of difficulty for prohibited drivers to circumvent the system.”

FMCSA offers answers to dozens of frequently asked questions about the clearinghouse.

-- James Jaillet contributed to this report