North Carolina’s state police raised more than a few eyebrows last year when news emerged of a highway ramp parking enforcement blitz near the winery of a well-connected donor to the current governor’s campaign. According to the Charlotte Observer’s exposé, the winery owner had complained to the governor about the rigs. Subsequently, the dogs were unleashed, and the newspaper reported the state tripled the number of parking tickets written to truckers in 2015 over 2014.

According to North Carolina-based owner-operator William McKelvie, following the widespread criticism that followed, such business has quieted for the most part. “Lately, I’ve seen more guys on the ramps, but I haven’t seen state troopers bothering them,” he says.

During the North Carolina State Highway Patrol’s Motor Carrier Enforcement Section’s routine safety enforcement inspections that happen at weigh stations (35 percent of the time) and at roadside (65 percent), officers by and large are “not looking to jam up guys who are decent,” McKelvie believes. He testifies to fairness in all of the recent inspections he’s had there, including two in June within the week around the annual Roadcheck blitz, one at a scale on I-85 and another at a roadside check.

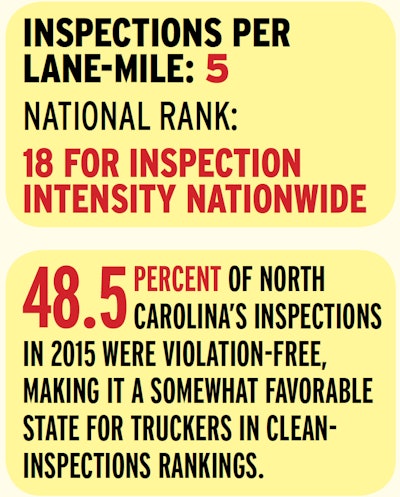

North Carolina’s roadside/weigh station inspection program ranks in the upper half of states for inspection intensity. But some measure of fairness is evident with its clean-inspections and violations-per-inspection rankings in the 30s among states. When truckers are inspected there, as also evidenced anecdotally, they’re more likely to walk away with a clean inspection than in well more than half the rest of the continental states.

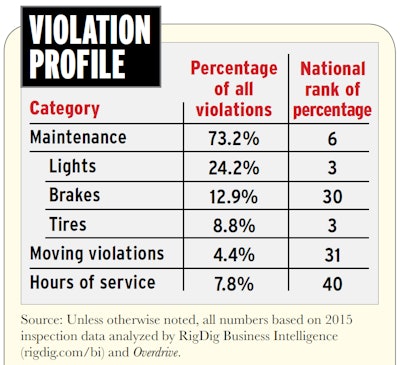

North Carolina’s roadside/weigh station inspection program ranks in the upper half of states for inspection intensity. But some measure of fairness is evident with its clean-inspections and violations-per-inspection rankings in the 30s among states. When truckers are inspected there, as also evidenced anecdotally, they’re more likely to walk away with a clean inspection than in well more than half the rest of the continental states.“Lights, brakes and tires,” says six-truck BPW (“Best Possible Way”) Transport owner Brad Wike, based in Charlotte-area Lincolnton, N.C. Those are the bedrock equipment concerns for inspectors nationwide that also drive Wike’s priorities when avoiding problems with violations for his regional dry van/flatbed business. Numbers in Overdrive’s analysis bear him out: Though North Carolina’s brake-violations ranking lags at No. 30, the state stands out for an uncommonly close focus on maintenance violations broadly, particularly those related to two of the most visible equipment problems. North Carolina enforcement ranks No. 3 in both tires and lights nationally, and No. 6 for maintenance overall.

For national evaluation of all of these violation categories, with interactive maps showing various states’ rankings in these and other metrics, visit the CSA’s Data Trail hub at this link.

For national evaluation of all of these violation categories, with interactive maps showing various states’ rankings in these and other metrics, visit the CSA’s Data Trail hub at this link.“The few things they’ve gotten us for, we got it honestly,” Wike says, including tickets for low windshield-washer fluid and a tire slightly low on air pressure. But such small violations can come at a hefty price — $100 for the washer fluid alone.

Treatment that’s more the norm among North Carolina inspectors that his fleet has encountered, says Wike, was evidenced by a recent out-of-service order BPW managed to avoid.

The inspector, in the course of a full Level 1 lookover, had the trucker bleed the air down. “The air beeper isn’t working,” the driver told Wike, referring to the alarm that is required to sound and display visually during any low-air event. An inoperable alarm is an out-of-service violation. After the driver consulted with Wike, however, he made it known to the inspector that the scale was just a few miles from the Caterpillar location that had done all of the recent work.

“Instead of putting him out of service, the DOT officer told the driver he could take it back to the Cat place and get them to fix it,” Wike said. “He didn’t have to do that. He actually helped us out when he didn’t really have to.” Though he did issue a ticket for the violation, it would have been a bigger hit to have been placed out of service and have “to call a service truck out to fix it.”

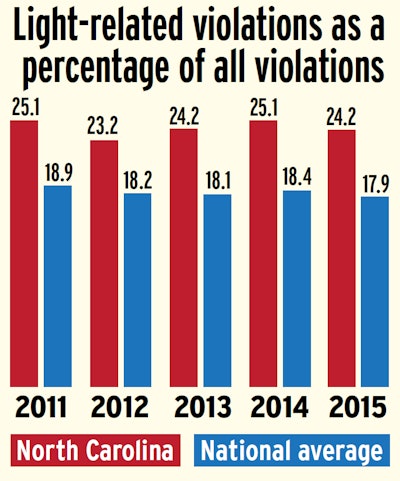

North Carolina, like the state of Ohio, profiled at this link last year, is something of a national outlier for perhaps the most visible of all truck-equipment violations, those related to inoperable or misisng lights.

North Carolina, like the state of Ohio, profiled at this link last year, is something of a national outlier for perhaps the most visible of all truck-equipment violations, those related to inoperable or misisng lights.Such treatment, as inspectors from North Carolina and elsewhere have noted, is a matter of officer discretion and thus can be influenced by all manner of things, from a truck’s exterior and interior appearance to the driver’s professionalism and congeniality.

“I think they’re pretty fair,” McKelvie emphasized about North Carolina’s officers. “But then again, you’re talking to somebody that doesn’t get out of the truck and cuss them out or disrespect them.” He says he stays clean-shaven and typically wears a nice shirt, jeans and work boots when he’s on duty.

McKelvie keeps his truck as clean as possible while hauling hoppers regionally. He believes that image helps what might be the most common result of any violation incurred during a run-in with a North Carolina safety enforcement officer. At the roadside stop during Roadcheck week, McKelvie was pulled into a median on a state highway, where the officer noted a simple problem. But, “instead of writing me up for it,” he waved the owner-operator on.

North Carolina Highway Patrol Officer C.V. Barrett in 2015 stressed the value he himself placed on interactions with drivers during inspections. While Barrett noted with pride that he led his unit in out-of-service orders, he didn’t lead in violations. Following the introduction of the Compliance, Safety, Accountability program, he had something of a “come to Jesus” moment on violations’ new import for a driver’s record and how that can affect his future employment and standing with his current carrier.

Barrett said he was careful about what he marked on inspection reports, never letting any out-of-service violations go but pointing out others to the driver that may not be safety-related. “Any violation I see, I’ll bring the driver out and point to what it is,” he said then. “I think it’s only fair.” Barrett said that if the driver obviously cared about what he was doing and the problem was remedied easily, odds are it wouldn’t appear on the final report or the driver’s or carrier’s record.

Next/related:

Find all of the CSA’s Data Trail state profiles via the links below: