Truckers are required to use a doctor on the National Registry of Certified Medical Examiners when getting their U.S. Department of Transportation physical examinations. Since that’s been the law for more than two years, every trucker who’s required to be medically certified at least every two years now should have been through a physical with a doctor on the registry.

Regarding sleep apnea, that’s significant. Apnea-screening protocols were included in training that all registry-listed doctors were required to take prior to being listed. Two identical Overdrive polls taken around the 2014 inception and two-year anniversary of the NCRME show that the percentage of drivers who’ve been tested for apnea grew from about a third of drivers to 46 percent, almost half.

However, inclusion of the screening protocols in the certification process has not totally cleared up the confusion and lack of precision surrounding apnea and related requirements for professional drivers. Those protocols, as well as newer proposed guidelines for apnea screening, have raised new concerns among drivers around whether testing referrals are justified.

The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration is pursuing a rulemaking that could bring clarity to these matters. The rulemaking route was required by Congress if FMCSA wants to act in a significant way on apnea, and signs are pretty clear that they’re moving in that direction.

FMCSA received input from the public at three listening sessions in May, likewise from a public comment period following an advance notice of proposed rulemaking that solicited comments earlier in the year. The agency’s Medical Review Board then drafted preliminary screening criteria that might serve as a blueprint for a universal screening protocol that eventually may be required by a rule.

Should it become regulation, according to analysis of an Overdrive survey that received more than 3,000 responses, the protocol would definitively screen 25 percent of the driver population not currently being treated for sleep apnea.

Because a third of respondents didn’t know their body mass index, the 25 percent could be as high as 38 percent if that third had a BMI and/or set of other factors that disqualified them. The true share lies somewhere between those percentages. Whatever the number, those drivers would face expensive testing, often paid for by the driver, and sometimes the loss of income due to time away from work.

At press time, the screening criteria were set to be further discussed at an Oct. 24-25 partially joint meeting of FMCSA’s MRB and Motor Carrier Safety Advisory Committee. A comment period that ends tomorrow is open for both meetings.

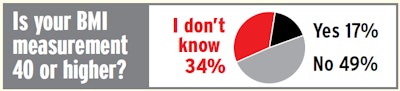

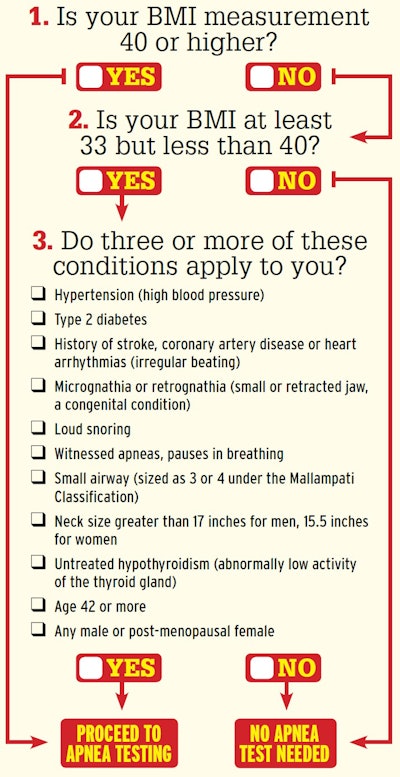

As drafted, the MRB criteria lean heavily on the body mass index measurement, a ratio of height to weight, to determine whether a driver would be screened. All drivers with BMI measurements of 40 or above (a 6-foot person who weighs 290 pounds or more, for instance) would be required to test.

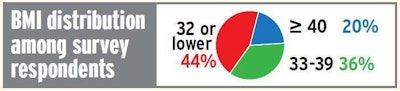

More than 3,000 Overdrive readers responded to a fall survey on sleep apnea. One in 10 reported they currently receive apnea treatment. Among those who weren’t currently being treated, the results above show a third of Overdrive survey respondents don’t know their BMI — easily 20 percent or more not currently being treated would be screened for testing under the review board’s recommendations as drafted this summer based on a BMI of 40 or above and no other conditions. Based only on the ratio of those who answered yes or no, 26 percent of readers would need testing.

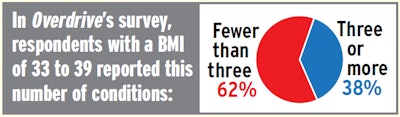

More than 3,000 Overdrive readers responded to a fall survey on sleep apnea. One in 10 reported they currently receive apnea treatment. Among those who weren’t currently being treated, the results above show a third of Overdrive survey respondents don’t know their BMI — easily 20 percent or more not currently being treated would be screened for testing under the review board’s recommendations as drafted this summer based on a BMI of 40 or above and no other conditions. Based only on the ratio of those who answered yes or no, 26 percent of readers would need testing.For a driver with a BMI of 33 or higher (e.g., that same 6-foot person at a minimum of 234 pounds), but less than 40, three among a long list of conditions would have to be met before drivers were referred for testing. One cause for alarm over the proposal is that two of the conditions apply to large numbers of professional truckers: being at least 42 years old, and being a man or post-menopausal woman.

Among those who reported a BMI measurement in Overdrive’s survey, less than half fell under the 33 BMI cutoff for the remaining apnea screening protocols outlined in the Medical Review Board’s preliminary recommendations.

Among those who reported a BMI measurement in Overdrive’s survey, less than half fell under the 33 BMI cutoff for the remaining apnea screening protocols outlined in the Medical Review Board’s preliminary recommendations.

Swift company driver and trainer William Stewart isn’t over 42, but his thyroid condition makes it exceedingly difficult to keep the pounds off. His weight is such that he would be referred for sleep apnea testing under the recommended screening protocol.

Click through the image or this link to access an interactive version of this checklist to find out whether you would be screened to be tested for sleep apnea under the Medical Review Board’s preliminary recommended criteria.

Click through the image or this link to access an interactive version of this checklist to find out whether you would be screened to be tested for sleep apnea under the Medical Review Board’s preliminary recommended criteria.If, of course, he hadn’t been already tested: With his medical certification this summer, for the first time in his 10-year career, he received a three-month conditional medical card and required a sleep test that he took at home. Results shared with Overdrive showed an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) measurement of 18 events per hour. Blood-oxygen saturation showed lows of 73 percent. The AHI measurement is on the low end of the “moderate” sleep apnea range by many estimations, though Stewart says the analysis of those results from the sleep doctors and certifying physician was confusing.

“They told me I essentially don’t have sleep apnea, that I don’t have a treatable case,” he told Overdrive. “They said if I wasn’t a truck driver, they wouldn’t even prescribe me a CPAP machine.”

When Stewart began using his continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine, the most common treatment for sleep apnea, he experienced the common difficult adjustment period of sleeping with a mask on his face. When he went back to redo his physical, his doctor noted the relative mildness of his case and said, “We might be able to see about getting you pulled off of this thing” with the next physical. Then, leaning in, the doctor noted, “If you lose some weight, there’d probably be a better chance of it.” It’s well-known that apnea often improves with weight loss.

“I’m getting this because I’m fat,” Stewart concludes. “I’ve never had any real problems sleeping.” Stewart is on his own self-styled diet and exercise program, and the weight is coming off fairly quickly from the nearly 450 pounds he was carrying in August.

Even with the weight loss and CPAP therapy, even though his AHI is down to an average 0.2 events per hour from 18, Stewart says his daily alertness hasn’t changed, though he’s never experienced the excessive daytime sleepiness many apnea sufferers report. His insurance covered a lot of the associated costs of the sleep-doctor visits, CPAP machine purchase, testing and follow-ups, but he’s still $1,500 lighter out of pocket to date as a result.

If MRB’s preliminary recommendations are adopted, Stewart may never be required to test again. That’s assuming his weight loss continues and his apnea is shown to be back fully in the mild or nonexistent range.

Such monitoring of marginal apnea cases is addressed in the recommendations in terms of the frequency of testing required for those who’d tested negative for apnea, or with a mild case not requiring treatment. Whether such might apply to the large share of operators who’ve been tested for apnea to date is unclear.

The recommendations say a new sleep study would be needed upon “the appearance of one or more additional risk factors beyond those that required the original sleep study, or a 10 percent increase in weight.” If passing the age of 42 is “the only additional risk factor,” the report recommends a three-year period between the prior sleep study and any new one.

A rulemaking could help put to rest once and for all any confusion about screening and testing for apnea. Given the pace of rulemaking, it likely will be years before anything is set in stone.