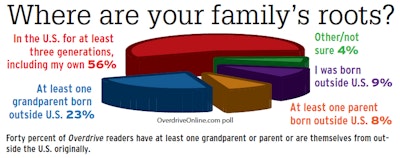

Sikhs have been a growing part of America’s professional driver force for three decades. Though there are tens of thousands of them in trucking, their non-Sikh counterparts have little information and a lot of misconceptions about them. They’re mostly second- and third-generation U.S. citizens, but often mistaken for Arabs because of commonly worn turbans and long beards.

That confusion began to change for some anti-electronic logging device-mandate activists in October when groups of Sikhs joined other passionate owner-operators to protest the implementation of the mandate. Owner-operators who’d never gotten to know this group of truckers found a new appreciation for a misunderstood and occasionally maligned group.

Pictured on the February 2018 cover of Overdrive is Racchpal Singh Dhillon, one of many Sikh truckers who went to Washington, D.C., to protest the ELD mandate last year. Dhillon came to the United States in 2004 from India and quickly earned his CDL. In 2014, he started his own company, OnTime Trans, based in Noblesville, Indiana. He now owns and operates 16 trucks. His wife, Nancy, emigrated from India in 2012 and now handles OnTime’s accounting, paperwork and management.

Pictured on the February 2018 cover of Overdrive is Racchpal Singh Dhillon, one of many Sikh truckers who went to Washington, D.C., to protest the ELD mandate last year. Dhillon came to the United States in 2004 from India and quickly earned his CDL. In 2014, he started his own company, OnTime Trans, based in Noblesville, Indiana. He now owns and operates 16 trucks. His wife, Nancy, emigrated from India in 2012 and now handles OnTime’s accounting, paperwork and management.Scott Reed, among organizers of a part of the October protest events that happened in Washington, D.C., sees those efforts as improving the ties that bind “the cultural diversity among truckers. … You got the American-bred boy trucker standing there right next to the guy that came from India … fighting together. To see the way that took place, learning from each other – we broke some stereotypes down there.”

Organizing the activist Sikhs came about in part due to the efforts of Gurinder Singh Khalsa of the Indianapolis-based Sikhs Political Action Committee. He argues the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration has not approved each of the dozens of ELD devices and that the mandate will result in economic hardship.

In October, SikhsPAC announced a partnership with Forrest Lucas, founder of Corona, California-based Lucas Oil Products, to fight the ELD mandate. They made their case in Washington, D.C., along with protests there from other groups. Concurrently, three California rallies in Sacramento, Fresno and Bakersfield were organized and attended by Sikh truckers.

A convoy that started at the Sikh Temple in Yuba City and rolled through Sacramento capped the protest week. A later ELD protest rally in Yuba City coincided with the 38th annual Sikh Parade, the largest Sikh event outside of India.

As Overdrive went to press, SikhsPAC and a group representing Punjabis with roots in northern India petitioned FMCSA for a delay in ELD compliance for small business trucker members and members who haul agricultural products.

Khalsa says Sikhs have been growing trucking businesses in America since the 1980s. That’s when waves of immigrants came here fleeing anti-Sikh violence sparked by the 1984 assassination of Indira Ghandi, India’s first female prime minister. Most Sikh truckers are owner-operators based on the West Coast and in geographic clusters that include Indiana and areas in New York, New Jersey and Virginia, among others.

SikhsPAC chairman Gurinder Singh Khalsa, left, was active in lobbying against the ELD mandate. Sukhwant Singh owns Taste of India restaurant at Spiceland (Indiana) Truck Plaza.

SikhsPAC chairman Gurinder Singh Khalsa, left, was active in lobbying against the ELD mandate. Sukhwant Singh owns Taste of India restaurant at Spiceland (Indiana) Truck Plaza.Khalsa says he and other Sikh immigrants gravitated to trucking for its business potential. He and his brother started a trucking company in 1998.

“The goal was to work hard, earn a good living and get your own authority as soon as possible,” he says. The tight-knit community expanded to help transition newly arrived Sikhs into trucking. Trucking schools such as Fresno, California-based Dashmesh Trucking School catered to Sikhs.

“For the newly arrived Sikhs fleeing the genocide in India, language was a barrier at first,” Khalsa says. “There was an effort then to penetrate the trucking industry, where a strong work ethic made trucking a good path. Once we became business owners, we could not only provide for our families but also stay faithful to our beliefs.”

Now there are as many as 150,000 Sikhs in driving jobs ranging from Class 8 long-haul to local delivery and vocational work, estimates SikhsPAC.

For Manpreet Singh, an Indian-born trucker who came to the United States in 2010, providing for his family of five makes him proud to be a trucker.

“I’m very grateful to contribute to the American economy,” says Singh, who’s based in Noblesville, Indiana. But he wishes his fellow truckers knew more about Sikhism and understood how much they have in common rather than their perceived differences.

When the opportunity arises, Singh will try to explain his beliefs, including why he wears a turban, to his fellow truckers. “Some are interested,” he says. Others, including dock workers, continue to berate Sikh drivers, accusing them of being Muslim terrorists, he says.

Research shows that most Americans know little to nothing about Sikhs. Mistaken perceptions have resulted in verbal abuse, violence and discrimination against Sikhs since 9/11.

But there are other challenges that come from following their religious beliefs. Because traditional Sikhs don’t cut their hair, some have run afoul of corporate policies at fleets that require hair samples for drug testing.

Harsimran Kaur, senior counsel for the Sikh Coalition, a legal defense group, was the lead attorney in a case involving J.B. Hunt Transportation and four Sikh truckers who refused to provide hair samples. The four reached a $260,000 settlement with the company in November 2016. As part of the settlement, J.B. Hunt agreed to amend company policies to comply with federal anti-discrimination laws.

“No one should have to face humiliation because of their religious beliefs,” said lead complainant Jagtar Singh Anandpuri. “I have been driving a truck for years, and I know there is nothing about my faith that interferes with my ability to do my job.”

Kaur says she’s not heard of further complaints about hair testing obstacles since the case and supports companies that want to explore more extensive testing options, such as nail testing. “We are not asking the industry to weaken their testing or safety standards,” she says. “We are just asking [them] to accommodate religious articles of faith.”

While the FBI reports only seven documented “hate crimes” against Sikhs in 2016, Kaur believes those numbers are higher because the FBI relies upon cases voluntarily reported by law enforcement. She says the Sikh Coalition alone received 15 such complaints in 2016 that the group investigated.

Laramie, Wyoming-based small fleet owner-operator Mintu Pandher says the people he encounters throughout his travels treat him with respect. “I’ve been here for 17 years, and I’ve never had any issues.” Pandher stands out with the traditional Sikh turban and beard, though he often dons a hard hat instead when at a location requiring it.

For Sikhs, a small minority in India, there is no “my country back home,” he says. “If you live somewhere, you defend that place. … Since I’m living here, this is my land. It’s a defensive instinct.”

Turbans were adopted as protective headgear of sorts in centuries past when Sikhs were warriors, fighting the Islamic Mughal empire invaders, he says. Pandher believes this to be a distinct difference between American-Sikh culture and that of non-Sikh immigrants from other traditions. Relatively few Arab-Americans, for instance, wear the headgear in the United States, he says.

Sikhs are free to affiliate with any political party, and Khalsa believes his good relationship with former Indiana governor and current Vice President Mike Pence helps the Sikh community. Sikh leaders encourage their people to become active in their communities, and the ELD protests show how such efforts can help change attitudes.

Scott Reed and Pennsylvania-headquartered Landis & Sons owner-operator Mike Landis say they walked away from the D.C. protests with a new appreciation for Sikh truckers.

“I grew up with 9/11 happening when I was in high school,” says Landis, who runs his independent business in a 1999 Peterbilt cabover. “I’ve always been pretty closed-minded about anyone who wears a turban or looks remotely anything like the terrorists do. I’ve never really been ashamed to say that.”

Landis had been told the Sikhs are a peaceful people, but didn’t care, continuing to resort to false stereotypes. “But when they showed up [for the Washington, D.C., protests] and they wanted to shake our hands and thank us for being there, and seeing how many of them showed up, I would say it was four-to-one they outnumbered us ‘proud loud-mouthed Americans,’ ” he jokes.

“Then here you have these people who know a lot of people look down on them just because of how they’re dressing and how they look, and they’re thanking us for being there in our trucks. It was extremely humbling.”

Reed says he also “ate crow” over his own past statements in the wake of the D.C. demonstrations, and he believes ripple effects from a new appreciation and a sense of unity will continue for years.

“Man, I really feel like a piece of crap for feeling and thinking the things I’ve felt over the years,” Landis adds. “I’ll never feel the same way about them again. I’d defend them with everything I’ve got if I had to.”

Also in this series: