Small-fleet compliance with stipulations outlined in the Food Safety Modernization Act is required as of last month (larger fleets’ compliance deadline was a year earlier). “Simply put,” says transportation attorney Henry Seaton, “the FSMA really didn’t change any best practices” already in place around the refrigerated food hauling sector, just “required new housekeeping items” for such carriers.

“The Food and Drug Administration has done a good job getting it all online,” Seaton says of new training modules that carriers can use to satisfy the fairly simple stipulations in the law around training and documentation of that training.

The new training modules are downloadable free of charge via this link.

Generally, carriers are responsible for being able to provide upon request by any broker or shipper/receiver and/or their loading/unloading personnel information about previous loads hauled in any trailer, documentation of the vehicle’s cleaning (for instance, wash-out receipts could be asked for) and proper pre-cooling.

Much of the burden of new FSMA-related compliance falls on actual shippers of perishable foods, and there’s some evidence of overbroad interpretation of the rules and willingness of shippers to use contracts to “cram down” much of the responsibility on carriers, Seaton says. “Some particularly large food shippers have concluded wrongly … that FSMA requires shipments in which seal integrity has been compromised to be dumped.”

That’s not the case, he says, and clearly outlined in regulatory docket comments highlighted by the people at Travelers Insurance. Some commenters on the rules that ultimately implemented the requirements of the FSMA within FDA worried “that the proposed rule can be interpreted broadly enough to create potential issues if broken seals or evidence of tampering create a presumption of adulteration [of the cargo], absent any evidence of actual threats to the public health,” according to text accompanying the final rule. Regulators “made revisions to [the final] rule that address the concerns of these comments.”

For the purposes of “assessing transportation equipment and transportation operations,” FDA went on, the agency noted it would still rely generally on previously existing law related to seal integrity and existing standards for determining what Unit Manager Craig Leinauer of Travelers Insurance characterizes as bedrock risks from a cargo insurance perspective of “spoilage and contamination. … There’s not a new insurance peril that was created” by FSMA. “Spoilage and contamination remain the risks.”

At once, he acknowledges early readings of proposed-rule language created a misunderstanding that could be driving the issues Seaton’s seeing examples of in broker/shipper contracts with carriers.

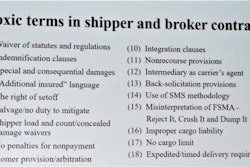

Seaton provided three contract language examples that he says show shippers going well beyond minimum requirements and giving carriers little recourse in the event of an issue as minor as a broken seal or even a simple failure to conform to a delivery appointment time.

Example 1

Click through the image for a larger view of the text here, from a contract (party names redacted) that gives the shipper full control of the ability to salvage any load deemed adulterated, often a last resort for reefer carriers if a load is rejected. FDA inspection and further salvage can partly relieve the burden of the loss, but here the carrier remains totally at the whim of the shipper by contract. With shortened lead times in grocery supply chains as a result of what Seaton calls the “Amazon effect, “more shippers are washing their hands of having to deal with” prior standard processes for non-first-rate loads. As Seaton says, the accepted practice has been that, “if it gets to the consignee and it doesn’t look first-rate, an inspector comes in and writes up a report, then it’s sold as salvage. It’s a gleaning process. It’s eaten by prisoners or goes to food bank” or other location.

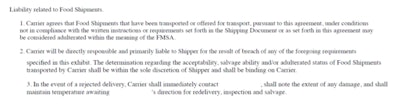

Click through the image for a larger view of the text here, from a contract (party names redacted) that gives the shipper full control of the ability to salvage any load deemed adulterated, often a last resort for reefer carriers if a load is rejected. FDA inspection and further salvage can partly relieve the burden of the loss, but here the carrier remains totally at the whim of the shipper by contract. With shortened lead times in grocery supply chains as a result of what Seaton calls the “Amazon effect, “more shippers are washing their hands of having to deal with” prior standard processes for non-first-rate loads. As Seaton says, the accepted practice has been that, “if it gets to the consignee and it doesn’t look first-rate, an inspector comes in and writes up a report, then it’s sold as salvage. It’s a gleaning process. It’s eaten by prisoners or goes to food bank” or other location.Example 2

Click through the image to increase its size. This contract language, with party names also redacted, likewise gives the shipper the full control of how to handle rejections, leaving carriers little recourse for losses that could be, as stipulated, the result merely of a broken seal.

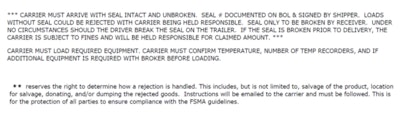

Click through the image to increase its size. This contract language, with party names also redacted, likewise gives the shipper the full control of how to handle rejections, leaving carriers little recourse for losses that could be, as stipulated, the result merely of a broken seal.Example 3 provided by Seaton is from a broker’s load confirmation that goes into detail in assigning a large swathe of broker/shipper responsibilities to the carrier and includes this language related to salvage of loads for little more than a broken seal or late delivery: “If [BROKER NAME REDACTED]’s or a shipper’s instructions require a cargo seal, the lack of a seal or seal irregularities shall be sufficient to consider the shipment unsafe and a total loss. CARRIER agrees that when transporting food for human consumption, late delivery, i.e. delivery after the deadline indicated on the transportation documents, alone shall be sufficient to reject a shipment and consider the cargo a total loss.”

Seaton says, hypothetically, “If a shipper makes a more rigid requirement that has nothing to do with the freight’s [quality], they can dump the product. … If it’s rejected because it’s five hours late getting to [the destination], they want it trashed. The small carrier that signs that contract – and doesn’t have insurance for that” kind of loss – “and if the carrier doesn’t have the right to inspect” then it becomes an uninsured loss. “A contract is a risk-transfer device – a small carrier can’t afford to assume an un-insurable risk. For a guy who’s got two trucks, a $40,000 claim, and he needs the money to operate, the legal system doesn’t give him any recourse.”

Travelers Insurance, at least, does have broken-seal coverage among its cargo insurance offerings, says Scott Cornell, company transportation business lead. “We try to also work with carriers … to avoid that kind of question coming up about a load” by recommending seal-containment boxes or other equipment/procedures.

Many insurance carriers popular with owner-operators and small fleets do not provide such coverage, Seaton says.

Says Leinauer, “The FSMA regs give the shipper wide berth to contract some of the sanitation requirements away. We do see shippers forming contracts with carriers that push the sanitary requirements down on them. We advise carriers to read those contracts carefully. If there is a reassignment of those responsibilities, you have to understand what you’re getting into.”

The “mischievous thing” about the language examples above is “it’s not what the law requires,” Seaton adds. “The practice of simply rejecting edible food products and requiring dumping is unconscionable and unsustainable.” Such contract provisions “are typical of the type of contract cram-down that is becoming all too frequent with the full implementation of FSMA.”

Seaton for the past couple years has been trying to “get these small carriers to a place where they can warrant to the shipper [and broker] that they comply with the FSMA” via the Uniform Food Safety Transportation Protocol, a system developed by Seaton with a variety of industry-participant partners. By joining the USFTP with an annual fee ($100), it gives carriers the ability to enable easy verification of their compliance with FSMA by freight partners, creating a binding relationship. “The idea was that if the brokers would come along and agree to it they could easily vet two-truck Charlie without waiting on a certificate of insurance,” he says. “We were trying to make it easy for shippers and brokers to vet carriers. We didn’t want to have the same thing with food safety that has happened with plaintiff’s bar and lawsuits” over crashes. “There ought to be a level playing field” among carriers of all sizes.