This isn't the first time I've started a Channel 19 post this way, but given the similarities of the circumstances of this particular case (and the one I last wrote about, at this link), it all bears repeating pretty much verbatim:

I’ve written numerous times about avoid-like-the-plague “right of offset,” or set-off, language in contracts between carriers and partner brokers. Such language allows a broker the right to offset carriers' freight payments to recoup the value of cargo claims that arise and aren’t covered by the carrier's cargo insurance. The broker at least believes itself then free to deduct the cost of that claim from future loads hauled, to the benefit of the customer making the claim, and the broker's benefit in that customer relationship.

Except it doesn't always work. Take a small fleet associate who will remain unnamed in this story and his large-broker customer who began withholding $18,000 worth in load payments for well upward of 100 days, claiming a right to do so given cargo damage incurred on a prior load that was being valued at that level. What the trucker had been hauling when said damage occurred was a piece of expensive robotics that had been internally secured to a custom-built pallet -- the trucker was instructed by both the broker and the broker's customer to not secure the approximately five-feet-tall piece by sending straps over the top of it, but only to secure the pallet itself to the flatbed on which it was loaded.

The carrier's driver did just that. "The pallet we were securing was a cushioned pallet, specially made" for the cargo, the small-fleet owner said, "and they strapped their cargo to that. We strapped only through the pallet."

End result? The shipper's internal strapping broke in transit and the cargo "fell forward against the bulkhead of the truck," the carrier said. "There was apparently damage we couldn’t see – everything was boxed."

Given the carrier had followed the shipper's instructions to a tee, he told the broker neither he nor his cargo insurance would be held responsible for the load. "We did exactly what they wanted," he added, yet the broker "kept insisting we had to pay and, soon after, began withholding load payments" due to the carrier on continuing business with the broker.

They got paid for that load, but four others went unpaid for months to come.

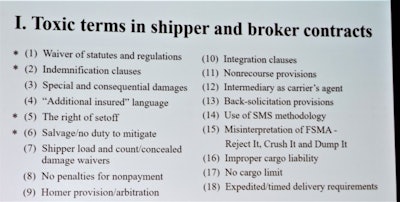

Contract language can come back to bite you in all sorts of ways. At the National Association of Small Trucking Companies' annual conference two weeks back, longtime transportation attorney Henry Seaton's session sought to emphasize offset/set-off language in addition to a myriad of other clauses carriers ought to keep their red pen handy for deletion before they think about just "signing to see what happens next," he said.

Shown here is what regular readers might well remember Seaton once called his "Dirty Dozen" broker/shipper contract no-nos for carriers to look out for -- clearly more of a Baker's Dirty Dozen, plus a few more, now.

Shown here is what regular readers might well remember Seaton once called his "Dirty Dozen" broker/shipper contract no-nos for carriers to look out for -- clearly more of a Baker's Dirty Dozen, plus a few more, now.

In addition to the "right of set-off" or offset that the carrier's case above illustrates, Seaton has found in recent history No. 15 on his list to be particular onerous. It refers to a common misreading of the Food Safety Modernization Act by some large shippers, he said, quick to reject loads of perishables for as little as a broken seal. Through contracts then, they cram down responsibility for the destruction of the load on the carrier. It's an issue Seaton previously outlined for me as part of this piece of reporting from 2018, when FSMA's requirements for carriers were coming into play.

Such policies, Seaton said, directly contradict what's actually in FSMA. "Their interpretation says if a shipment 'could be contaminated, it must be destroyed.' That's not what the law says," but rather: "if there's reason to suspect contamination, it should be inspected to make the determination."

Food banks, he wagered, would testify that there are "perfectly edible foodstuffs run around the food banks and not being given to the poor because of this misinterpretation. If the goods are still internally packed" and they're being dumped, "it’s just plain wasteful and unconscionable."

And expensive to dispose of in both time and money for the carriers involved.

[Related: Food Safety Modernization Act's requirements of perishables haulers, and unintended consequences]

Seaton made reference to a longstanding inspection practice by operations like Front Street Commodities, a "large, reputable" company, he said. "They will inspect cargo and tell you the diminished value, and will offer a price to you. There are established ways that have been around for years to handle particularly produce and it’s not 'reject it, crush it and dump it.'"

Seaton's spent recent years grading contracts based on their inclusion of the 18 onerous phrases shown above, he said. While he urged the carriers in attendance at NASTC's meeting not to accept them, or at the very least think long and hard about signing anything containing them, he also held out hope for work on what he called a "simple and fair, bilateral contract" small carriers and brokers might utilize to better standardize responsibilities and avoid cram-down by the shipper.

In the case of the set-off practice, though, the shipper could well represent a carrier's best opportunity to exercise leverage to get paid.

Here's how the carrier's case above resolved.

After all the months that went by, with four load payments for work done for a single one of the broker's shippers essentially being held hostage by the broker exercising the set-off right, the carrier had gotten the run-around one too many times. He'd asked who exactly had made the decision to withhold those load payments and had been perhaps predictably shuttled between this contact in Accounts Payable and this other contact in an adjacent department, and on and on. "They sent me to some obscure person in yet another department," then, and he'd decided enough was enough.

He sent an email to a contact with the shipper of multiple loads for which he had not been paid by this point. He made note of that fact and illustrated for the shipper the amounts he was due, noting he was fairly certain the shipper had paid the broker by then. He asked for help to resolve the situation.

As Truckers Justice Center attorney Paul Taylor wrote here in Overdrive earlier in the year, if a shipper hasn't signed the "non-recourse" provision on the bill of lading and you haven't signed away your right in your master hauling contract with the broker to seek payment from the shipper (see No. 11 on Seaton's list above), you may well in fact be on solid legal ground to go after payment directly from the shipper.

[Related: What are your rights when a broker doesn't pay?]

That wasn't exactly what the carrier in this case was up to with his message to the shipper, but it got the shipper's attention, and ultimately found its way to the broker.

"This wasn’t even a customer [of the broker] that was involved" in the original load that had been damaged, the carrier noted. He's not sure even if his broker's contract prevented him from seeking payment from the shipper. To him, it didn't matter. The broker "also has an agreement to pay us," the carrier said. "If they breach the contract by not paying us, none of it is valid. That's how I look at it.

"They knew we were right, they just wanted to see if they could push us around" to recoup their customer's losses on the damaged load, and cover their own balance sheet in the process.

Broker payment offset/set-off rights in the contract: that's the vehicle with which they tried to do that, but this carrier was ultimately paid what he was due -- and still does business with the broker today, lending credence to they knew we were right, wouldn't you say?

As I began this story, so will I end it, as the conversation around this issue over the last decade doesn't really seem to have moved the needle with some of the biggest brokerage operations out there. Here we go, mostly as I wrote the last time this issue reared its head here on the blog.

Refer also back to the words of broker Eric Belk, who in a 2016 op-ed noted the abuse of right-of-offset clauses such as this as an issue ripe for regulatory oversight, if brokers themselves don’t do more to tamp down the practice. The broker was then (in 2016) preparing to remove offset/set-off language from “his company’s own standard contract (a provision he said they’d never enforced, anyway) as a way to hopefully lead by example to avoid the potential eventuality of the dreaded R word. As broker Belk wrote: “If we don’t become proactive with regulating this issue ourselves, chances are someone or some industry organization will attempt to influence change with new regulations that limit the use of set-off rights.”

Year 2016 was not that long ago, but long enough to say that his words fell on certainly deaf ears when it comes to brokers like the one described above. I said it then and I'll say it again: Maybe now is the time, if nothing else, for a new look at your contracts with brokers with a red pen handy for some of that fine print.

[Related: The broker margin transparency federal law already affords carriers who request it]