Swept up by attempts to reign in worker misclassification are legitimate owner-operators who purchased their own trucks and contract under a larger fleet’s authority. California’s law, in a tense legal fight with trucking groups, could pave the way for similar laws in other states, should it prevail in court.

Swept up by attempts to reign in worker misclassification are legitimate owner-operators who purchased their own trucks and contract under a larger fleet’s authority. California’s law, in a tense legal fight with trucking groups, could pave the way for similar laws in other states, should it prevail in court.“I don’t want to move, and I won’t be a company driver.” Ivan Mikhov, a 34-year-old owner-operator based in Sacramento, Calif., faced grim prospects about the future of his California-based one-truck business in the waning months of 2019.

The state had enacted a law establishing rigid criteria, dubbed the “ABC test,” for determining whether a worker could be hired as an independent contractor, widely interpreted as banning fleets from contracting with owner-operator truckers.

Mikhov, who lives near family in Sacramento, told Overdrive in December he was weighing a move to Oklahoma as a way to keep his business alive. With his 2013 Volvo, Mikhov is leased to Landstar, one of many high-profile fleets to tell California-based owner-operators late last year that, because of the ABC test law, they need to leave the state or find a new fleet.

Court decisions in recent weeks, however, have turned the tide in trucking’s favor — and given those like Mikhov a tinge of hope.

U.S. District Judge Roger Benitez issued a preliminary injunction Jan. 16 against California’s act, Assembly Bill 5 (A.B. 5), forbidding the state from enforcing the law on carriers and owner-operators until a pending lawsuit brought by the California Trucking Association is heard and decided.

Opponents of the law believe it won’t hold up in appellate courts because of a 1994 act, the Federal Aviation Administration Authorization Act (FAAAA or F4A), which forbids states from enacting laws that “interfere with prices, routes and service” of motor carriers. In layman’s terms: The federal government, not states, regulates interstate trucking operations.

“I’ll be an owner-operator, even if I have to move,” says Mikhov. “But as of right now, the judge says we’re exempt, so I’m going to stay and wait on a decision.”

California-based owner-operator Ivan Mikhov. He leases his 2013 Volvo (pictured here) to Landstar.

California-based owner-operator Ivan Mikhov. He leases his 2013 Volvo (pictured here) to Landstar.The California Trucking Association estimates some 70,000 owner-operators would be impacted by California’s directive, many of them, like Mikhov, forced to choose between their home and their livelihood.

Though California’s law has drawn the most attention, similar legislation has popped up in New Jersey, New York and Washington, among other states. It’s a ballooning threat that could undermine the ability of owner-operators to haul for fleets. Trucking groups and attorneys, however, say they intend to fight the laws as they arise, hoping to see the courts shoot them down and preserve the leased owner-operator.

New Jersey appeared poised to follow in California’s footsteps late last year. But the recent court orders in California have slowed efforts there. Instead, the state’s legislature and its governor opted for a more muted set of misclassification laws just this week.

Meanwhile, in Illinois, “conversations have started,” says Eric Gallien, associate director of the Illinois Trucking Association, as to how the trucking industry in the state would navigate a potential bill there. So far, none have been filed, though The Washington Post reported this month that Illinois legislators were preparing a bill similar to California’s.

Sheri Call, executive vice president of the Washington (state) Trucking Associations, is on the front lines of the legislative battle brewing over the ABC test there. Bills introduced last year have not advanced, she says, and the legal fight in California has caused state legislators to pause.

Andrea Marks, head of grassroots organization TruckerNation, said her group is attempting to educate its members in the states highlighted here (Oregon, Washington, Illinois, Wisconsin, New York and New Jersey) about the rise of ABC tests. Bills mandating ABC tests have been introduced in Washington, New York and New Jersey, while the Illinois Trucking Association says it’s preparing for a bill to be filed in that state. No such law has been filed in Wisconsin, and Oregon seems likely given its political leanings and its location. Owner-operators “are extremely vital to trucking industry,” says Wisconsin Motor Truck Association President Neil Kedzie. “We’re hoping that type of legislation does not come into being here in Wisconsin,” he says, as such laws threaten “the ability of small operators to exist and to be competitive.”

Andrea Marks, head of grassroots organization TruckerNation, said her group is attempting to educate its members in the states highlighted here (Oregon, Washington, Illinois, Wisconsin, New York and New Jersey) about the rise of ABC tests. Bills mandating ABC tests have been introduced in Washington, New York and New Jersey, while the Illinois Trucking Association says it’s preparing for a bill to be filed in that state. No such law has been filed in Wisconsin, and Oregon seems likely given its political leanings and its location. Owner-operators “are extremely vital to trucking industry,” says Wisconsin Motor Truck Association President Neil Kedzie. “We’re hoping that type of legislation does not come into being here in Wisconsin,” he says, as such laws threaten “the ability of small operators to exist and to be competitive.”“I’m excited to see the emphasis on F4A and federal pre-emptions. Due to what’s going on California, carriers in Washington are already looking at morphing into an all-employee-based driver model.”

Call and WTA are trying to impress upon legislators the importance of leased owner-operators. “It’s natural for trucking companies to rely on independent contractors to expand their business when they need to. And independent contractors are contractors for a reason,” she says. “They like owning their own truck and their own business. Some of our largest carriers today started three decades ago with a single truck.”

Carriers in Washington report that many of their contractors clear over $100,000 a year, Call says. Likewise, Illinois owner-operators “are able to earn well in excess of what a company driver can earn,” says Gallien, citing his association’s research. ABC test laws “take away opportunities” for those truckers, he says.

The ABC test derives its name simply from being a three-point method for determining whether a worker can be classified as an independent contractor. For trucking, it’s the B prong that causes trouble, stating that a contractor’s tasks must be “outside the usual course of business of the company,” effectively forbidding for-hire freight carriers to hire contracted drivers.

Attorneys have expressed confidence they can beat ABC test laws in court — even if they have to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“It seems headed in that direction,” says attorney Greg Feary, partner at transportation specialists Scopelitis, Garvin, Light, Hansen and Feary. “And I do think it will be resolved in favor of the trucking industry.”

Attorney Bob Roginson, who’s heading the California Trucking Association’s lawsuit against A.B. 5, says he’s prepared to see the lawsuit through to the Supreme Court. Roginson is a partner at Ogletree, Deakins, Nash, Smoak & Stewart.

The F4A argument against A.B. 5 has been regularly cited in opposition to state transportation laws. It was cited by Benitez in his broader Jan. 16 injunction decision and by a California state court the week prior in a decision blocking A.B. 5 enforcement for Cal Cartage, an N.F.I subsidiary.

![“I’m not counting my chickens before they hatch,” says Jimmy Nevarez, who runs small fleet Angus Transportation out of San Diego. He who contracts with a handful of owner-operators. “It seems hopeful now, but I’m hoping that it gets solidified [permanently].” Likewise, his owner-operators are relieved by the decision, he says. “They’re happy contractors. They don’t want to move elsewhere and they don’t want to get their own authority.”](https://img.overdriveonline.com/files/base/randallreilly/all/image/2020/01/ovd.JimmyNevarez-2020-01-24-10-17-e1579882798697.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&q=70&w=400) “I’m not counting my chickens before they hatch,” says Jimmy Nevarez, who runs small fleet Angus Transportation out of San Diego. He who contracts with a handful of owner-operators. “It seems hopeful now, but I’m hoping that it gets solidified [permanently].” Likewise, his owner-operators are relieved by the decision, he says. “They’re happy contractors. They don’t want to move elsewhere and they don’t want to get their own authority.”

“I’m not counting my chickens before they hatch,” says Jimmy Nevarez, who runs small fleet Angus Transportation out of San Diego. He who contracts with a handful of owner-operators. “It seems hopeful now, but I’m hoping that it gets solidified [permanently].” Likewise, his owner-operators are relieved by the decision, he says. “They’re happy contractors. They don’t want to move elsewhere and they don’t want to get their own authority.”

Benitez will hear CTA’s case against A.B. 5 at the District Court level. The case, likely to be appealed no matter what Benitez decides, will then be heard by the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. The decision from there will likely be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, and justices would have to vote on whether to hear the case.

“I think it’s likely to get to the U.S. Supreme Court,” says attorney Jason Geller, managing partner at Fisher Phillips’ San Francisco office. The firm works with trucking companies nationwide on labor disputes. “Trucking is a unique industry,” he says. “This wholesale change to the standard could potentially upend the entire industry.” The argument being, he says, “if this type of change needs to be made, it should be legislated at the federal level and not piecemeal by states. That’s a strong argument.”

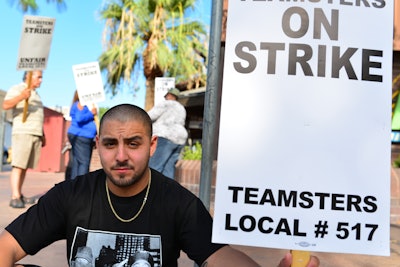

Some states and pro-labor groups like the Teamsters, which has been advocating heavily on behalf of California’s A.B. 5 and for similar legislation in other states, argue that ABC test laws are needed to halt the exploitation of workers who would enjoy better benefits or protections if they were employees.

Even the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association initially cheered A.B. 5 as a chance to end what the group said was a “plague” of “lease-purchase schemes” that bilk drivers. OOIDA has since reversed course, expressing opposition to A.B. 5’s ABC test mandate, stating it’s overreaching.

More broadly, the rise of the “gig economy,” thriving in California, has left state legislators, especially in progressive states like California, grasping for ways to regulate and maintain enforcement of fair labor standards. The “gig economy” refers to a heavier reliance on independent contractors, such as Uber drivers, instead of workers in a traditional employee-employer relationship.

The Teamsters union is a major proponent of stricter regulation of worker classification. Teamsters Local 517 represents milk haulers and bus drivers, as well as many non-driving professionals. This photo was taken in 2014 during a strike against the Golden Empire Transit District in Bakersfield, California.

The Teamsters union is a major proponent of stricter regulation of worker classification. Teamsters Local 517 represents milk haulers and bus drivers, as well as many non-driving professionals. This photo was taken in 2014 during a strike against the Golden Empire Transit District in Bakersfield, California.The Teamsters have been one of the strongest proponents of laws to regulate worker classifications. The group declined to talk with Overdrive, but pointed to Teamsters President Jim Hoffa’s statement after A.B. 5’s September passage. “Misclassification is an attempt to weaken the power of workers, including the thousands of truck drivers in California who deserve a living wage and full rights as employees,” Hoffa said. With A.B. 5, “California has taken a strong stand with workers who should earn a living wage and have the protections to which they are entitled.”

The union says drivers misclassified as contractors are missing out on owed benefits and state-granted employee protections. The union intervened on behalf of California to help defend A.B. 5 against lawsuits, such as the one brought by the California Trucking Association and two owner-operators, Ravinder Singh and Thomas Odom.

Feary rejects the Teamsters’ argument — and thinks the courts will too. “Owner-operators who are intentionally establishing themselves as entrepreneurships and businesses feel like these laws are being applied to them to take their business away,” he says.

The cry from leased owner-operators “is far louder than this narrative being spun by pro-labor that everybody wants to be an employee. If a guy wants to be an employee truck driver, there are many, many opportunities to do that,” Feary said, pointing to the tens of thousands of job openings at fleets for company drivers.

For now, in California, trucking operations are unchanged, given Benitez’s ruling — a temporary, yet promising turn for those in the state whose operations were in jeopardy.

“I’m not counting my chickens before they hatch,” says Jimmy Nevarez, who runs a small fleet out of San Diego and who contracts with a handful of owner-operators. “It seems hopeful now, but I’m hoping that it gets solidified [permanently].” Likewise, his owner-operators are relieved by the decision, he says. “They’re happy contractors. They don’t want to move elsewhere and they don’t want to get their own authority.”