The top doctors studying sleep agree on one thing: Trucking's hours of service regulations do not set up professional drivers for restful nights or long-term health. In fact, they serve as a pretty serious barrier, and with operators experiencing poor health outcomes and increased risks of things like diabetes, heart disease and obesity, it's time to get serious about fighting back.

Hours of service regulation "goes against the nature of our body clocks," said National Sleep Foundation Vice President Dr. Joe Dzierzewski. Dzierzewski and the foundation last week promoted what they call "Drowsy Driving Awareness Week," and he said truck operators face increased risk of being involved in a drowsy driving accident, but also the long-term impacts of disrupted sleep.

"Research shows upwards of 15% of all big rig crashes have fatigue or sleepiness as a cause, and there's a lot to be done in terms of driver awareness," said Dzierzewski. The NSF has a handy guide on strategies to fight drowsy driving, most of which simply recommends healthy, consistent behaviors that Dzierzewski admits can be hard in the OTR lifestyle.

Often enough, demands of a particular load, or the preferences of individual operators looking to avoid increasingly hairy daytime traffic, mean truck owner-operators move at night. The International Agency for Research on Cancer made no bones about it in 2019: night shift work is "probably carcinogenic," the organization said. Though a small but significant share of Overdrive's owner-operator readers have noted more daytime truck traffic since the electronic-logging-device mandate came into play in late 2017 (which comes with its own risks), night work remains common for many; Dzierzewski pointed to an associated "increased rate of stroke, heart attacks, depression, and anxiety" as well as more vehicle crashes for people who consistently work nights.

[Related: View from the road: ELD mandate increases pressure on operators, in more ways than one]

It all comes down to the circadian rhythm -- the natural tendency of humans to sleep at night and work during the day. One of the world's top researchers on the subject, who practically introduced the concept to the world by writing 10 books and more than 140 scientific papers on the topic, is Dr. Martin Moore-Ede. The researcher's lately been on a crusade against one great modern killer of sleep: Cheap blue lights.

Moore-Ede, who has done extensive work related to hours of service regulations (demonstrating in 2007 a need for increased flexibility for operators with sleeper berths, among other things), said that today's HOS regs aren't exactly circadian-friendly, but the negative effects can largely be mitigated with a simple change of lighting.

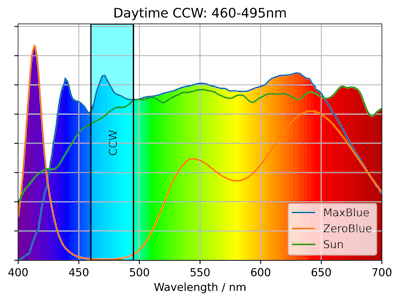

LED lights have become the norm in electronic lighting from sleeper cabs to smartphone and tablet screens, and they "produce white light with a big pump of blue" in it, he said. "The blues are causing a problem. You need it during the day, but during the night you need to take it out."

This blue light is ubiquitous across all kinds of devices now because it's cheap. LEDs can efficiently convert electricity into light by doing it at frequencies that produce a lot of blue. Moore-Ede now works as the Chief Medical Advisor at Korrus, a company that says it's found a way to remove the harmful blue light and replace it with violet hues with a light that's still very efficient and not noticeably different.

It's important to note that neither the old blue-blocker shades at convenience stores nor your expensive Mac computer really work as advertised. Moore-Ede said they're not really blocking the right blues in the spectrum, and in the case of screen dimmers, the screens still use blue-heavy LEDs. Screen dimmers "are merely adjusting the color temperature of the light -- an aesthetic fix after Apple got very nervous when media came out with stories that blue light makes you fat."

A chart from Korrus shows the band of harmful blue lights used by current LEDs, as well as their ZeroBlue solution and the sun itself for comparison.

A chart from Korrus shows the band of harmful blue lights used by current LEDs, as well as their ZeroBlue solution and the sun itself for comparison.

Moore-Ede said research firmly supports that just a few days worth of night shift work under blue lights has a negative influence on sleep pattern, appetite, obesity and diabetes risk.

"You can make someone diabetic just by the simple thing of keeping them up all night under regular blue-rich LED lights," he said, citing studies of glucose tolerance. LEDs in trucks and logistics offices are "energy efficient and cheap, but it kills you. You don’t have to wait for a cancer diagnosis. There's a very measurable type of effect."

Do these lights look strange to you? They're Korrus' circadian-friendly lights that replace harmful blue light with violet light in a way that's hardly noticeable to the eye or on an electric bill.Korrus

Do these lights look strange to you? They're Korrus' circadian-friendly lights that replace harmful blue light with violet light in a way that's hardly noticeable to the eye or on an electric bill.Korrus

Korrus manufactures and sells its own lights, and also has licensed its technology to other device makers. Moore-Ede suggested trucking could benefit from putting these lights in sleeper berths and dispatch offices.

"There are big benefits in terms of sleep and alertness and fewer errors, particularly in LTL hubs and warehouses with people doing all this sorting and unloading," he said. "That's a place where you can put in proper lighting and it takes the risk factor out of the equation." He likened the damage done by blue lights to jet lag, a "real nightmare" that can take days or weeks to recover from.

Both Moore-Ede and Dzierzewski agreed that it's probably smart to limit screen time and blue light exposure before bedtime, and for kids as well.

As for the hours of service regulations, Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administrator Robin Hutcheson said recently the organization had no plans to add greater rest flexibility than what already exists following the 2020 split-sleeper changes. " We’re not looking at further changes right now," she said in an October interview with Matt Cole and Todd Dills of Overdrive. She hoped a driver compensation study and infrastructure improvement, among other initiatives, would yield safety benefits long-term.

If Moore-Ede and Dzierzewski's research is right, perhaps the agency should consider promoting awareness of blue light's effects. Owner-operators who put good emphasis on sleep and control those environmental factors likely can reduce the risk not only of crashes, but also silent, slow killers like diabetes and cancer.

[Related: ELDs and highway safety: Crashes, injuries and fatalities rise post-mandate]