It's called "the Amazon effect," after the e-commerce giant's ability to remake the internet, then industry, and then the world in its own image, and it's been eating away at the long-haul segment of the trucking industry for years. But even as Amazon builds more warehouses and distribution centers, and consultants, tech leaders and some politicians imagine a world with more regional, short haul trucking, the over-the-road segment has stood its ground, Overdrive's reporting finds.

Over the past decade, Overdrive has tracked a decline in the length between pickup and delivery of the average owner-operator's load. With the last update, in 2018, the decrease in miles seemed tied to the growing uptake of electronic logging devices preceding the then-new ELD mandate. Yet the trend has in some ways continued into 2022, with a new survey indicating that, yet again, average length of haul seems to Overdrive readers to be dropping.

Compare the chart above -- which shows 52% of recent survey respondents seeing no change, 31% seeing shorter hauls, 12% longer -- to the 2018 Overdrive report that found 47% of haulers reporting similar haul length, 48% reporting shorter trips, and just 5% seeing longer runs.

The strong trend through these surveys depicts a shrinking length of haul, and the graphic below exhibits exactly where operator sentiment lies in regard to that phenomenon.

Today's owner-operators show only a slim plurality of preference for hauls between 250 and 450 miles, a trip within whose range sit runs that can be completed in a day (some with the return included). From there, preferences swing between short and long, with the shortest and longest ranges -- 1-100 miles and more than 1,000 miles -- ending up dead last in ranked preferences.

These data show owner preferences aligned with time spent -- a 1-100-mile haul too short to be worth the time spent at multiple load and unload locations in a single day, a 1,000-plus-mile haul too long for some to get back to the home base as much as desired.

Consider the example of owner-operator Eddie Yousif of Phoenix, Arizona, who mostly hauls construction materials on a flatbed today. He simply "got tired of not being home" with his young children. Yousif completely exited the long-haul game. He felt that was right for him in his stage of life, and now his business works with a large company where he simply calls dispatch and gets a load, operating more locally than prior.

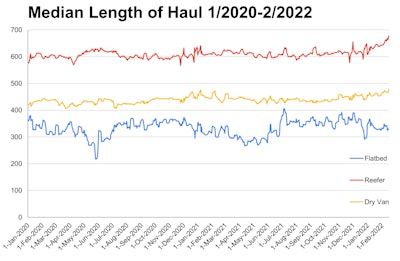

At once, the trends on the spot market these last few years present a counter to the increased preference for shorter runs on display in the charts above. DAT told Overdrive its load board has actually seen an increase in median trip length for both vans and reefers, even as Amazon doubled its physical warehouse and distribution center space to more than 420 million square feet from 2019 to 2022.

[Related: Three common fallacies in today's popular 'driver shortage' arguments]

“Long-term, the trend is likely being driven by shifting warehouse and transportation networks. Short term, it’s more attributable to inefficiency," said Ken Adamo, DAT’s chief of analytics. "You have rail issues, fixed networks in shambles and a litany of other reasons why truckers are hauling longer. Heck, we saw examples of dray moves from Baltimore to Buffalo.”

According to Vise, the big shift in trucking employment has been migration from big carriers with locked-up contracts with shippers to tens of thousands of new small carriers that scoop up opportunities across the haul-length spectrum on the spot freight market, with those big carriers eventually hiring on more drivers for shorter, regional hauls.

"In March 2020, we had just under 203,000 for-hire carriers holding authority, not counting bus operations and counting one-truck operations as a trucking company," said Vise. "As of the beginning of this month we have around 320,000." This nearly 60% spike in the number of new trucking businesses wasn't initially captured by the BLS, and the major driver of the shift, according to Vise, wasn't Amazon, but drivers using the pandemic's scrambling of freight networks as an opportunity to open their own business.

Think back to the spring and summer of 2020, as the CARES Act, signed into law by then-President Trump, showered money on drivers, many of whom were furloughed in the early days of the pandemic. Not only did Paycheck Protection Program loans come online for business owners, but stimulus checks hit blue-collar bank accounts and independent contractors became eligible for enhanced unemployment benefits. With time off and a surplus of cash, by June and July a record number of operators had gone independent.

At the same time, big fleets furloughed drivers and severed relationships with independent contractor owner-operators. Shippers hesitated to lock down contracts. As a result, Vise describes a monumental shift to the spot market. Big brokers and newer players like Convoy and Uber Freight increasingly allowed smaller carriers to "manage one truck operations about as effectively as an asset-based carrier," he said.

[Related: No Turning Back: New era for direct freight]

For some owner-operators, capitalizing on increased demand and choice in haul length, runs are indeed getting longer. Billy Beech, an owner specializing in heavy-haul work in the wind energy sector, understands where fellow owner Eddie Yousif is in life, desiring more home time. But after 46 years of driving, Beech's children are grown and he's back out over-the-road. Based in Tennessee, Beech says these days he's hauling as far as he ever has, with frequent trips from Florida to Oregon topping 2,500 miles. The long, predictable, oversize hauls allow Beech to confine his driving to daylight hours and enjoy a sit-down supper and breakfast most days.

"E-commerce runs at all times of the day and night. I just don’t want to run all night," Beech said. "I could see if you live close to a warehouse if you wanted a regular run and they pay enough money. it would be a pretty decent thing. But it's not anything I’ve thought about. It came about a little bit too late in my trucking career."

But as Beech pointed out, local hauling becomes attractive when there's a warehouse near you. And with Amazon and other retail giants expanding their reach, there's likely to be more and more local hauling work available, and they'll be more and more accessible to the geographically diverse trucking population.

Overall, Amazon's strategy is to build more warehouses, shorten haul length, and eventually transition to zero emissions vehicles that aren't likely to pull off such long hauls for a long time. The Biden Administration has expressed interest in funding "regional hydrogen hubs" and other clean-energy investments that rely on shorter-haul logistics, and corporate America certainly seems taken with climate-conscious freight operations.

In the final analysis, though Amazon benefited tremendously from the pandemic-induced shift to e-commerce, it's not in a position to dictate the economy to the extent that long-haul trucking could disappear anytime soon. As long as those well-entrenched "inefficiencies" DAT's Adamo described exist, demand for over-the-road trucking, and the owner-operators ready to provide it, stand to cash in.

[Related: The not-so-long haul: Operational challenges to owner-operators after the ELD mandate]