In recent weeks, it has been hard to look at a newspaper or tune into the business news without seeing a headline about so-called “trucker shortages.”

This is not a new conundrum, of course. Talk of labor shortages always tends to bubble up whenever the freight market tightens for an extended period. There’s no denying that right now, businesses and consumers alike are feeling the effects of near-term demand spikes -- and the supply chain’s immediate limitations, including “driver shortages,” to address this demand. Even so, the current chatter feels extreme.

To some degree, labor shortages are now, and have always been, somewhat of a Rorschach test: Employers looking to hire tend to see shortages around every corner and workers seeking work perennially see seemingly simple solutions in higher wages and more on-the-job training.

For most people, the idea of a labor shortage is fairly straightforward: When demand for a particular type of worker exceeds supply, that’s a shortage. But the whole concept gets muddier once you move beyond the knee-jerk intuition of Economics 101. The current industry conversation falls victim to three common fallacies.

[Related: The disconnect between the money and the 'driver shortage' mantra]

First fallacy: Incomplete information

First is the fallacy of incomplete information.

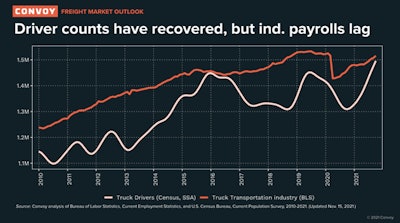

Two pieces of data are commonly used to support the idea that there is a trucker shortage: The employment level and average wage reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) monthly Current Employment Situation report (often referred to as the “Jobs Report”).

On the surface, the interpretation of the employment level and growth rate of wages should be obvious: As of late November, the number of seasonally-adjusted trucking industry jobs remained slightly below where it was right before the pandemic, and transportation worker wages have been growing at their fastest pace since the early 1980s.

But beneath the surface, things aren’t what they seem.

The BLS employment data are based on “payroll employment” -- which only counts the number of workers on employer payrolls. For most industries, that’s fine, but it’s a big problem in trucking because it excludes independent contractors. In 2021 independent drivers were the fastest growing segment and now account for nearly 40 percent of truckers, by my estimation. Yet they aren’t included in the data that is often the basis for the “shortage.”

[Related: 'Driver shortage' claims miss self-employment explosion]

In addition, workers who are between jobs -- having quit a prior job and already having lined up their next one -- are not counted in the BLS payroll data. During periods when the quit rate accelerates, such as the present, the payroll data probably undercounts employment. Given the current industry quit rate, this matters to the magnitude of 6,000 to 11,000 workers nationwide who have jobs but who aren’t being counted as employed in the official statistics due to definitions and data collection practices.

There are a number of other issues associated with the average wage rates reported in the monthly Jobs Report -- most prominently, the fact that it makes no attempt to control for the shifting composition of the workforce. (For example, historically, when new college grads hit the labor market each June, average wages dip -- if nothing else, that’s because entry-level workers tend to be paid less than more experienced workers, pulling averages where college grads are highly represented down slightly.) The key to note is that the data doesn’t show wage growth for individual workers, but rather it shows wage growth across a constantly shifting pool of workers.

Equally important right now: Wages are nominal -- not real (inflation-adjusted) -- wages. Like an all-in brokered rate after weeks of fuel-price hikes, when inflation accelerates as it has in recent months, wage growth looks stronger than the purchasing power workers actually feel. So while recent nominal wage growth for transportation and warehousing workers was an eye-popping 8.2 percent annually in October 2021, real wage growth was a much more modest 3.4 percent. That’s still high compared to the essentially zero growth in real wages over the past two decades, but it’s still low relative to other service sectors. (Like the data on employment levels, the BLS wage data exclude owner-operator income performance.)

All in all, accounting for owner-operators, truckers who are likely between jobs, and statistical quirks of the wage data shows a definitively more mixed portrait of the trucking labor market: Driver employment has in fact rebounded to levels back at or even slightly above where it stood before the pandemic (see the chart above showing “Truck Drivers” numbers from the Current Population Survey, including owner-operators). Wage growth has picked up, too (though only modestly after accounting for inflation), largely because trucking wage growth for so much of recent history was so dismal.

Once we acknowledge the reality that employment levels have recovered more than conventional metrics would suggest, it begs a difficult question: Why is there a “shortage” of truckers now, when there wasn’t a shortage in January 2020? (Recall that, back then, industry headlines focused on carrier bankruptcies due to the soft market environment and a market surplus of haulers.)

[Related: Capture 2020 vision with proactive attention to repair, operating and finance costs]

Second fallacy: Conflation of short- and long-term shortages

The answer, of course, is demand -- and that is the crux of the second common fallacy behind the current labor-shortage angst: Too often the conversation around worker shortages conflates cyclical (short-term) shortages with structural (long-term) shortages.

There remains enormous doubts as to whether the current level of elevated freight demand associated with the pandemic -- the shift toward e-commerce, associated port backlogs, accommodative fiscal and monetary policy, elevated grocery and at-home food spending, reduced length of haul as supply chains realign -- will endure once economic life “normalizes” (whatever that means). Indeed, most trucking experts agree that freight demand will, sooner or later, decline from its current level. If that does play out, and depending on the magnitude of the decline, then it is very likely there are currently sufficient drivers to service that reduced level of aggregate demand.

[Related: Intermodal haulers fight off a 'system collapse' at ports]

Third fallacy: Misunderstanding of basic economics

The third and final common fallacy is a fundamental misunderstanding of long-horizon economics -- what economists would call “general equilibrium analysis” as opposed to “partial equilibrium analysis.”

To this point, the conversation about worker shortages is in many ways reminiscent of the hysteria surrounding the idea of “peak oil” that attracted attention in the 1970s and then again in the 1990s. (In its original formulation, this was the belief that any finite resource would eventually be exhausted for any level of consumption demand.) While few would dispute that there is some theoretical limit to the supply of oil barrels (or of truck drivers), time and time again economic history shows that high prices drive innovation, which pushes outward the production frontier allowing the economy to meet incrementally higher levels of demand with fixed (or even reduced) supply.

This is, of course, already happening in the trucking industry. Drop-and-hook and power-only options allow owners and drivers to more efficiently use their time by not having to wait at facilities, paperless BOLs and automatic detention mean less time doing paperwork, to cite just a few examples.

None of this would deny the immediate-term reality that many trucking companies are having to hustle to attract drivers -- especially new industry entrants who have lots of alternatives in booming adjacent sectors like last-mile/parcel delivery and warehouse work. There’s little doubt that the current labor market favors job seekers. Competition for experienced drivers is tough. The recent-history surge in new one-truck carrier authorities appears to be driven mostly by older workers returning to the labor market after a brief hiatus; they’re not going to be around forever. But to blame current market conditions on a true long-term labor “shortage” is to oversimplify a more checkered reality and to overlook a number of inconvenient facts.

Simply stressing out over labor shortages is short-sighted for any industry. Innovating to increase productivity – getting more out of the time you have, chiefly, for an owner-operator -- is a more viable long-term solution.

[Related: Know the value of your time to assess true profit]