Coming out of the pandemic, spot freight markets presented drivers with some of the best conditions in trucking's century-old and turbulent history, but as spot rates have softened for vans and reefers and diesel prices remain very high in recent weeks, some in trucking media are predicting a "trucking bloodbath" and a wave of bankruptcies to hit smaller, newer trucking companies.

Leading the charge to warn of an incoming "freight recession" is the FreightWaves publication, where in just the last few weeks CEO Craig Fuller has published a series of articles resurrecting the bloodbath terminology the entity used in 2019, a tough year capped off by the December failure of truckload giant Celadon. Bloomberg, one of the top news websites for stock watchers and traders, ran with Fuller's analysis and warned in its daily newsletter of a coming crunch. Since the doomsaying predictions went mainstream, many of the top publicly traded fleets have seen their stock drop double digit percentages. Yellow Corporation, for example, was down nearly 50% since the end of March, while Schneider National went down nearly 20% over the same period.

Yet it's not hard to find trucking economists and analysts who don't buy the hype. Other analyses point out that, while historically hot freight markets may slow down, demand levels are quite likely stay well above 2019 levels, with plenty freight to go around.

Is a 'freight recession' imminent?

Just a few months after trucking's owner-operators posted their best-ever year for income/profits, the war in Ukraine exacerbated already rising fuel prices, and a COVID outbreak in China's export-heavy southern regions threatens to jack up commodity prices, stymie the flow of freight, and generally throw a wrench in the gears of an otherwise humming engine.

"Generally speaking, when the spot market is good, it only lasts six to nine months, but we’re going on almost two years and counting with very little end in sight," ATBS Vice President Mike Hosted told attendees of Overdrive's Partners in Business seminar at the Mid-America Trucking Show in Louisville, Kentucky, last month.

If the timing mentioned by Hosted makes you nervous, you're not alone.

The February/March spot market demand metrics comparison presents a stark picture, beyond seasonal declines for vans and reefers in the typical spot market trough. While DAT Freight & Analytics reported a 2.2% increase in spot load postings overall for the month of March, truck posts increased much more, 29%, sending the van load-to-truck ratio plummeting 37.7%, reefer load-to-truck almost 39%.

That same month, as any owner-operator well knows, fuel prices rose 26% nationally, and now sit 62% higher than the same time last year.

Between February and March, the all-in van spot rate dropped 6 cents on average on DAT load boards, and so far in the first few days of April, the average has dropped another 8 cents. Things were more dramatic in reefer rates, which have fallen from $3.59 in January to $3.26 so far in April.

If rates continue their brisk decline and diesel prices don't budge downward, Fuller predicted some of the 130,000 or more new trucking fleets that entered the market since the dawn of the pandemic will go broke, and that trucking will enter one of its frequent and fitful recessions.

The word recession undoubtedly stokes fear, and Eric Starks, CEO and Chairman of FTR Transportation Intelligence, sought to clarify just what's being bandied about now by media prognosticators. "If the definition of a 'freight recession' is coming off of a peak and going back to a normal level, then we’re in for a [freight] recession," Starks said. "But I don't think that's what's being discussed here. If we go into a real recession, where things start to fall off and freight truly declines, where things don’t normalize but actually weaken, that's a real recession. Normalize just means we're not going to see 20% to 30% increases in freight rates, just more in the normal three to five percent range" over the course of a year.

[Related: Keeping cool, in control as difficulties heat up: Was truck ownership supposed to be this hard?]

Fuller pointed to measures of inventories, once gutted by the pandemic-induced boom in ecommerce, now showing warehouses once again brimming with goods -- yet another indicator suggesting likely demand decline, or normalization in Starks' view. The hot spot freight markets of the last nearly two years were in some measure a result of consumers shifting their spending from services and experiences to durable goods, things that need shipping. As COVID restrictions lift and consumers go back to spending money in movie theaters and restaurants, and not buying up patio furniture and other home goods, such thinking goes, freight markets will undoubtedly suffer.

According to Starks, however, this kind of argument underestimates the universal nature of freight demand.

"If you look at what freight gets moved, 70% to 80% of it is manufactured goods and the rest is consumer goods," said Starks. "Even if the consumer demand starts to ease, then manufacturing says 'I'll take that truck.'"

What's different now has a lot to do with supply -- trucking capacity writ large. In a high-demand, high-rate environment like that of the last two years, Hosted noted in the PIB presentation, typically "trucking companies buy all the trucks and hire all the drivers they can and flood the market. Generally speaking, we shoot ourselves in the foot" with too much capacity, "but we can't do that now," and haven't done it for two years, given supply chain constraints continue to limit truck availability.

"This is a good thing," he contended, "and these shortages are going to keep us profitable."

Global supply chain headaches disrupting everything from OEM build completions by holding back semiconductor production to owner-ops simply trying to change their oil have gone from being a lead weight tied around trucking's ankle to something of a safety harness keeping it from an abyss.

But it's not all rosy, of course, when it comes the outlook.

[Related: Despite record freight markets/income, challenges remain for owner-operators]

Where's the biggest risk when freight rates drop?

Ultimately, Starks doesn't see a recession, which he'd classify as a couple of down quarters for freight, as likely. But Starks, like ATBS President Todd Amen as well, does note that even short of a recession, a certain group of owner-operators who bought equipment at too-high prices to cash in on high rates are quite likely to get crunched.

Plenty among owner-operators, unlike most sizable fleets, end up buying fuel at the pump price. With those prices soaring and sometimes a considerable lag between the owner's cash outlay and the load's value and/or fuel surcharge recouped, the recent rate drop and fuel hike create a tricky situation.

Starks said it's not uncommon now to see trucks that used to sell for $30,000 or $50,000 going as high as $90,000 on the used market, but that you'd be "crazy" to expect prices to stay that overheated for long. "We clearly expect the owner-operator to be the one who bears the brunt of all of the pricing impacts we see due to fuel," he added, predicting that used truck prices would begin to normalize in tandem with rates normalizing to an extent and truck manufacturing getting back in its typical groove.

But therein lies the problem. Used truck prices soared due to a shortage of new equipment, which itself owes to labor and components shortages. Of the 130,000 new carriers since the pandemic, the wide majority are one or two truck operations driving used trucks, according to Amen.

"The saving grace of the last two years has been that a typical great trucking economy never lasts more than 12-18 months," he said. "The industry buys too many trucks, entices too many drivers, and even if the economy is good" the industry's over-buying still drives down the price of freight.

But during the pandemic, large fleets haven't been able to add new trucks, according to Amen. "No large truck lines have grown capacity," said Amen. "You can add 100,000 trucks with the mom and pops when you have huge truck lines not adding capacity, and we still have an undersupply of trucks."

[Related: Small fleets in the catbird seat for growth: For-hire-carrier size over the pandemic period]

Even if spot rates continue a downward trajectory into the typically strong Spring freight season, owner-ops can take their trucks into contract work with big fleets.

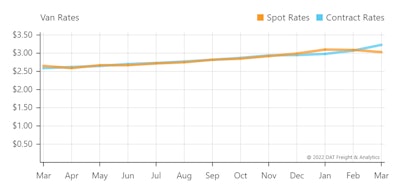

For the first time in the last year, average spot van rates fell below contracted rates, which continued to rise, in March.DAT Trendlines

For the first time in the last year, average spot van rates fell below contracted rates, which continued to rise, in March.DAT Trendlines

If rates and fuel prices don't add up to profitable loads for owner-ops on the spot market, "they finally park the truck and walk away," said Starks. "The other option is contract myself back out to a large carrier because I want to be able to continue to work. In this situation, you probably have overcapacity within the spot market, but that doesn’t necessarily mean overcapacity in the contract market."

The fact is that freight rates on the spot market have softened, and they've done so against a historic jolt in fuel prices. But rates still sit much higher than prior to previous "freight recessions," like the COVID-shutdown-inspired one in April-May 2020 and the slower decline in 2019.

Operators seeing higher earnings unlocks another type of slack in the freight market that could make business safer for new entrants, according to Amen.

"One thing nobody really talks about is that drivers work less when they make more money, " said Amen. "In the last two years, our average client made $71,000 and the year before they made $67,000," but they did it on thousands fewer miles. "We took a ton of capacity out because drivers don’t want to work as hard" if they don't have to.

[Related: Could record owner-op income, despite cost inflation, be longer-term trend?]

If loads end up less profitable, Amen noted operators would likely do what they've done time and again through the years: put on the miles, taking more loads.

"There won't be an explosion of bankruptcies," said Amen, "but there will be some."

Smart owner-operators have indeed been sidelined by rapidly rising fuel costs, but in this case took the time off breathe, and renegotiate loads that no longer made financial sense given the price of fuel. Both Starks and Amen agreed that recession was just too strong a word for what we're seeing now, and that the market may simply normalize around the new levels and distribution of capacity.

As noted, however, media predictions of a "freight recession" have already slammed big fleets' stock prices. Amen chalked that up to over-anxious traders and the inescapable fact that we're living through historically turbulent times.

A CEO of a big fleet may find their job in jeopardy just as much as a rookie owner-operator in 2022. "Just the fact of the matter is it’s going to be virtually impossible to beat your comps," or comparable performance metrics from the year prior, said Amen. "Last year was a record crazy year. Truck stocks have to have a reversal at some point."